Stefan Olander, vice-president of digital sport at Nike (below right), is sporting a Nike+ Fuel wristband for our interview at the Farringdon HQ of the brand's digital agency, AKQA.

The band, which tracks the wearer's activity through a sport-tested accelerometer, is still flashing red. This means Olander has yet to hit his goal for the day, an achievement that will be rewarded when it switches to green. Having just got off a plane, the most sedentary of times for global marketers, this lack of movement is unavoidable, even for a marketer from Nike, the brand which famously never stands still.

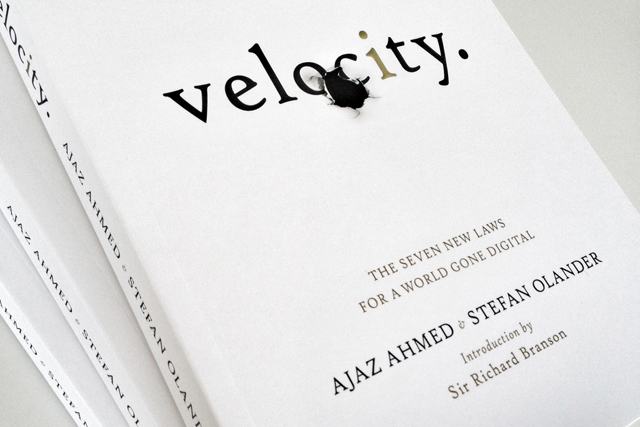

Olander has, however, achieved a more long-term goal with the publication of Velocity: The Seven New Laws for a World Gone Digital. Less a jargon-filled business tome and more a 'passion project' designed to give marketers and entrepreneurs the mindset and tools to create a better future, Velocity is the first book to be written by a marketer and his or her agency.

Olander has, however, achieved a more long-term goal with the publication of Velocity: The Seven New Laws for a World Gone Digital. Less a jargon-filled business tome and more a 'passion project' designed to give marketers and entrepreneurs the mindset and tools to create a better future, Velocity is the first book to be written by a marketer and his or her agency.

After many hours of conversations across multiple time zones, Olander and his co-author, AKQA founder and chairman Ajaz Ahmed, have distilled 12 years of working together into 248 pages.

It doesn't hold back. 'Many businesses are 'institutionally analogue', writes Olander, 'stuck in structures and logistical straitjackets that had an obvious function and rational purpose fifty, twenty, even fifteen years ago. But for the past decade that way of doing things has been evaporated.' The question Velocity poses, as does Marketing, is where do brands go from here?

You write that some businesses claim they are not technology companies and use that as an excuse to shy away from investment and organisational change. How has Nike faced this challenge?

Olander: When we repositioned (our investment in technology) as a consumer benefit powered by technology rather than IT, it made things much easier for everyone. All of a sudden, the investment is in your consumer and it becomes about demand-creation, which is a completely different approach.

If you want to be relevant in young consumers' lives and you don't understand the power and role technology plays, there is no way to be around them. Being a company propelled by innovation, it was pretty obvious where we need to be.

How can brands tackle this change? Is it vital to have the expertise in-house?

Olander: An instinct can be to outsource, but you need to assume ownership of your technological destiny. The story about Borders, which let Amazon handle its online sales, is one of the most telling examples of 'when you give up the direct connection to your consumer, you give up everything.'

How can marketers foster an innovation culture in businesses resistant to change?

Olander: To turn around a behemoth of a traditional company can be hard, but a great way of doing so, and it's the approach we take, is to create incubators - small units within a company that are truly empowered. You then use this as a catalyst for organisational change.

How will the social economy change business?

Olander: When you look at the monetisation of social media, I don't think the model has been cracked.

We see adding value to the consumer as key to growth. In contrast, advertising is an old model squeezed into the new framework of social where people don't want to be interrupted. I don't think this has been figured out; right now Google AdWords is the only real model that is clearly proven enough to work.

Ahmed: The challenge for brands is to create work and ideas that people want to share and that's how you get success in the social economy. If someone doesn't want to share it, then it might as well not exist.

All of Nike's different social channels add up to hundreds of millions of direct connections with the consumer. If you then provide an indispensable service to audiences, they share that and it has an incredible multiplier effect.

You write about Nike being a good editor-in-chief and curator. What are the skills that marketers need to survive in the age of 'velocity'?

Olander: The editing part is about us as a brand editing ourselves ferociously.

The consumer has so many choices, so we need to make sure we make the hard ones. One choice is in the product and experiences we provide, and second, through the meaningful connections we provide.

I used to run advertising for Nike, and we grew up being a company built on amazing athletes, products and advertising. We are entering a phase now where all our advertising still has an emotional value, but you definitely need to add a fourth level (to the business), which are indispensable services.

What do you see as the key new platforms and trends affecting brands over the coming months?

Ahmed: For us the dramatic shift that technology is going through right now is in two areas. The first one is simplification and the second one is making (interactions and experiences) more human. There is nothing natural in a mouse or a key-board as a way to communicate with your fellows.

That is one of the reasons why the growth of tablet computing or mobile phones with touchscreens has been so extraordinary: it is because touch, voice, gesture are incredibly human, instinctive and natural. This is where we will see fundamental shifts in technology.

At a time of information overload, are we at risk of a backlash against technological change?

Olander: There is innovation that is new and different just because it can be, and then there is innovation that is new and better.

As humans, we want things to be simple and more related to the things we know.

Email is an unbelievably inefficient way to communicate, stealing away millions of man-hours every year because of irrelevant information. But we have become so used to how easy it is to do, that we are not even questioning it. I am convinced the filters that are going to be applied to that way of communicating are going to be such that there is not going to be this plethora of unnecessary information any more.

Ahmed: One of the most fascinating things happening in the world right now is youth and the way they communicate. There is a whole generation who are confused as to why things are going backwards when they go into an office, whereas their experience outside is much more streamlined, much more efficient and much more focused. We are in this point of history where students can educate teachers and the next generation can educate the existing establishments on better communication.

In an Olympic year, how do you see consumers' relationships with athletes changing through technology?

Olander: We will always love athletes, and technology brings the athlete closer to the consumer. The reason we love the Olympics is because someone has prepared for four years of their life, with dedication and courage of human endeavour. The reason Nike succeeds in business is because we embrace this relentlessness and a lot of businesses could learn from athletes. When you lose this focus and fall into a sense of entitlement, you are in deep trouble.

How do you maintain this momentum and ensure Nike doesn't become out of touch?

Olander: Nike has a combination of youth and experience; youth is a mindset, not a demographic. For us it is about not getting stuck in our ways, but our athletes keep us young and energetic. You can never grow old when your consumer is young. l

Velocity is published by Vermilion, an imprint of Ebury Publishing (Random House Group)

AUTHORS' PROFILE

Stefan Olander is vice-president of digital sport for Nike. He oversees the company's global strategy for how digital technology will help athletes improve. Over the past 15 years, Stefan has been a core contributor in evolving Nike's consumer connections across the globe through his roles in EMEA, the Americas and, currently, at its global headquarters in Beaverton, USA.

Ajaz Ahmed is the founder and chairman of AKQA, the digital agency he founded when he was 21. Seventeen years later, he is in the same job at the company, the biggest and most-awarded in its field, with more than 1000 employees worldwide.