The general reception for deepfake technology in marketing and advertising circles has been one of excitement. A 北京赛车pk10 column last month went as far as suggesting: "The future of advertising could be staring you in the face."

The argument being, just as the Zao app allows users to put themselves in famous movies, brands could get super-creative and encourage the person in the street to star in their latest ad. It sounds like it could unleash a lot of creativity and engagement.

However, any brand manager who has ever done any work where creative decisions are handed over to the public will be wincing at that suggestion. You might be tempted to think the public would come up with something fun, like "Boaty McBoatface" for a new ship. In reality, the implications for brands could be dramatic if, or when, the public decides to put other people in their campaigns without their consent.

The technology could easily be used to embarrass a brand through a modern-day equivalent of the famous 2001 story of an MIT student trying to get Nike to print "sweatshop" on his trainers. The shoes were never made, but the story is still discussed today as an example of what happens when you put users in control.

There is also the possibility that it could lead to all kinds of hate speech being injected into ads. A brand may feel it can moderate any campaign that encourages deepfake spoofs to send them viral, but once that technology and the assets are released, is it realistic for companies to think they will still have control? Is it not a huge leap of faith to think videos they approve of would only feature people who have willingly given their consent?

Unleashing a brand threat

Silicon Valley has a history of releasing technology into the wild before executives have seriously thought through the consequences. We could debate whether the merits of social media outweigh the erosion of trust from the public for some media organisations to handle their data.

A better example to underline the threat would be blockchain. It is impressive technology, but it has been used one too many times by criminals to hide away their ill-gotten gains.

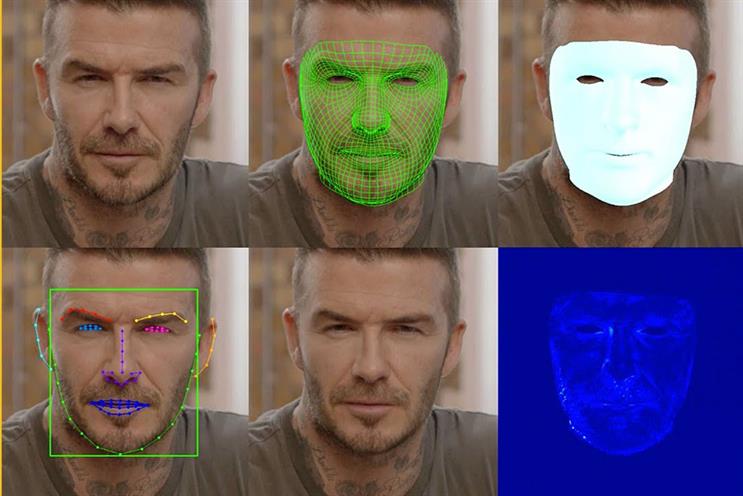

That is the point with deepfakes. The technology is hugely promising and could be used to great effect in the right hands. You only have to look at David Beckham (pictured in a demonstration of deepfake tech, above) being able to speak nine languages in a Malaria No More appeal to acknowledge there is a very good use for the technology. In addition to spreading a message of hope, the campaign shows how any actor or celebrity can literally speak to multiple markets without the need for dubbing or subtitles.

Undermining consumer trust

If the first question mark about deepfakes is the possible embarrassment for a brand when users personalise ads, the second has to be: what happens when rogue elements attempt to cause serious brand damage?

We have already seen how US House speaker has been made to appear to slur her speech, and a warning video of the power of the technology appearing to come from (but in fact Jordan Peele). has also fallen prey to the power of the technology through a deepfake in which he suggests he has stolen data and is inspired by Bond villains such as Spectre.

Facebook sees how the technology taps into the deeply worrying trend of fake news, with chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg revealing the technology could be banned on the platform, although the Zuckerberg video has not been taken down. It raises the question of whether brands could suffer damage if rivals were to issue deepfakes of a senior executive or a celebrity brand ambassador making offensive remarks or "admitting" a problem with its products or services.

The elephant in the room is that deepfakes are all about breaking trust and the technology is so good that it is hard to tell real footage from fake – and that’s only going to get harder as the technology improves. We will soon be at a point where it is virtually impossible to tell reality from fake and that is hugely worrying for all media companies.

We are already in the era of consumers not always knowing if they can trust what they read. But now we are on the verge of not being able to trust what we see. For a brand/customer relationship that relies on trust, this is deeply worrying.

Blaise Grimes-Viort is chief services officer at The Social Element