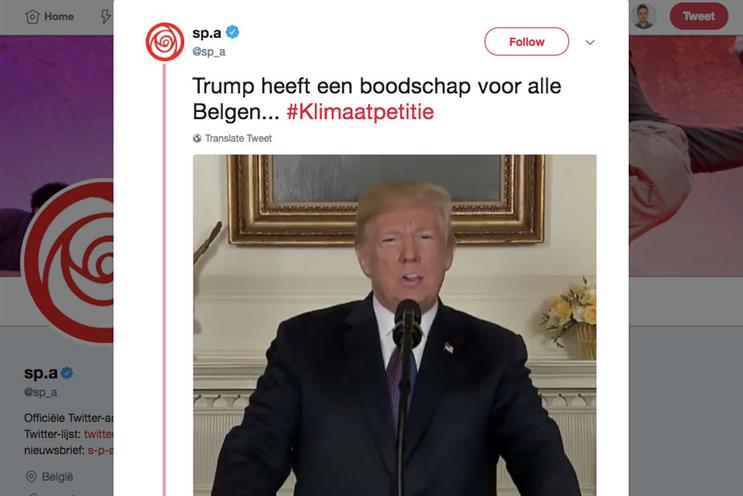

Socialistische Partij Anders (or ‘sp.a’), a political party in Belgium, recently ran a "deepfake" video to make it appear as if Donald Trump was asking Belgian voters to campaign to leave The Paris Agreement on climate.

The video aimed to remind Belgians that their country’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions were on a level that climate change deniers, such as Trump, would approve of. The punch line of the film has the US president saying: "We all know climate change is fake, just like this video."

This seems to be the first use of deepfake technology by a mainstream political party.

"Deepfake" is defined on Wikipedia as "an artificial intelligence-based human image synthesis technique... used to combine and superimpose existing images and videos onto source images or videos".

In short, it’s a technology that allows people to create fairly realistic face-and-voice-swap videos.

Like many internet technologies, deepfakes first emerged from the sex industry; deepfake tools were used to create imitations of celebrities performing in pornographic film.

It has of course been possible to create fake videos in the past, but it was very resource intensive; the CGI animation talent and computer hardware required was previously only found in post-production houses, so creating a fake video was an expensive pursuit.

Thanks to advances in machine learning it is now possible for a programmer – with knowledge of how to use neural network APIs – to quickly and cheaply create fairly realistic videos of anyone (including leading politicians) doing and saying whatever the programmer feels like.

The Atlantic published an article last week saying that deepfake tools could "make the current era of ‘fake news’ seem quaint".

As you can see from the sp.a example it’s currently not too difficult to spot that the video isn’t real (and the execution eventually reveals that it isn’t genuine); however its use should provoke concern.

It is very likely that this technology is going to get more realistic and it’s also probable that the tools to make deepfake videos will become much easier to use in the near future.

Mainstream companies like Adobe have already released tools that allow users to mimic someone’s voice using existing source material; it’s not hard to imagine them joining the race with to release a video equivalent that journeymen bloggers and bedroom video producers can use easily.

This means that in the near future there will be more deepfake videos that are more realistic, being made by more people, more often.

For those who worry about fake news poisoning democratic discourse, this technology is troubling.

Should political parties and campaign groups in the UK be allowed to use deepfake video in their political advertising?

There is no legislation to prevent them from doing so.

For example, if there was a second referendum on whether to accept the terms of the Brexit deal tomorrow, there would be nothing stopping groups sympathetic to the Remain camp making a film of Theresa May "privately airing reservations about the economic consequences" and putting significant online media spend behind it.

It has been reported that Trump is now claiming that he doubts the authenticity of the infamous "Access Hollywood" tape released shortly before the 2016 presidential election. While few give this credence, we need to prepare for a future when video is no longer a reliable source of truth in election campaigns (and more generally).

If we want to prevent deepfake video (and other future technologies with potential to unjustly distort debate) becoming a feature of our democracy, we need a framework for regulating what is and isn’t permissible in election advertising.

This is only the latest example of why political advertising regulation needs to be modernised for the digital world we live in.

The laissez-fair regulation that is in place in the UK (and many western democracies) is based on a legacy media environment where the press could mediate communication between politicians and the people.

But , parties and politicians are using online platforms to speak directly to voters.

In the past, political actors had to worry about difficult questions from journalists (and by extension backlash from voters) relating to dubious claims or bogus content; in the future, their questions are likely to be less effective.

If the twin forces of AI-enabled advertising and disintermediation between politicians and voters continue at their current pace – within a non-existent regulatory system – the misleading claims which we saw on both sides of the EU referendum campaign will soon look very quaint indeed.

The marketing industry can be proud of the way that it has taken on big societal injustices where the sector’s activity has historically had a negative contributing factor, such as portrayal of the disabled and the perpetuation patriarchy.

The restoration of democratically legitimate election campaigns is another issue where our voice is desperately needed. There is no other sector or organised lobby that can mount an informed and sustained campaign.

Given the reputational damage advertising more generally might suffer if political actors continue to take liberties with the principle of conducting only honest, truthful and decent advertising, it is important that we act now.

Benedict Pringle is the co-founder of the Coalition to Reform Political Advertising.