Epidemiology is evidence-based research.

The statistical evidence of data leading to a decision.

If we gather enough data, we must eventually come to the right conclusion.

But there’s another view.

The view that correlation does not imply causation.

In other words, the data may be right but the interpretation may be wrong.

The problem is the mind jumps to data as a conclusion instead of input.

For instance, in one study, the data showed women who had taken hormone replacement therapy had a lower incidence of breast cancer than women who hadn’t.

The obvious conclusion was that HRT lowered the risk of breast cancer.

But, actually, that was what a lazy reading of the data implied.

A more careful reading of the data showed that the women who took HRT were all from a higher socio-economic class.

They could afford HRT because they were better off, so they were able to afford private healthcare, gym memberships and a generally healthier diet.

Which may be the real reason they had a lower incidence of breast cancer.

An even more careful reading of the data would have revealed something else.

Among the women in the higher socio-economic bracket, those who took HRT actually had a slightly higher risk of breast cancer.

So the data, interpreted two different ways, actually showed two different results.

This is the problem with data: people avoid the discomfort of thinking.

We want to jump to the easiest, most obvious, conclusion.

What Buddhists call "the lazy mind".

This is particularly prevalent in advertising and marketing.

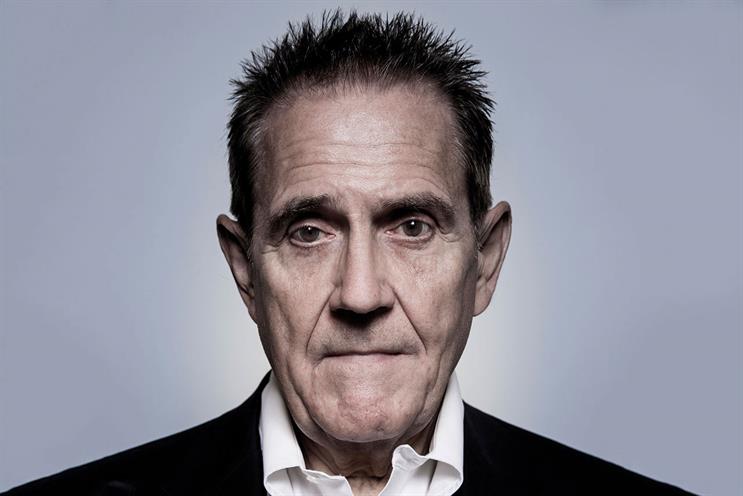

That’s what made John Webster different.

He used data as exactly what it was: information not conclusion.

Each time he would interrogate the data beyond the obvious surface reading.

For instance, his initial campaign for Sugar Puffs featured a small character called Honey Monster, based on Sesame Street’s Cookie Monster.

It loved the honey in Sugar Puffs and broke things if it couldn’t get any.

It bombed out in research – mums and kids hated the campaign.

Most people would start again, but John looked further into the data.

He found mums hated it because it was wilfully destructive – kids hated it because it was small and whiny, not much of a monster.

So John made it much bigger for the kids, and clumsy not naughty for the mums.

He also made it affectionate and gave it the line: "Tell ’em about the honey, Mummy."

With a different interpretation of the data, that campaign ran for nearly 30 years.

Paul Bainsfair often used the following example to explain the misuse of data.

In an experiment to discover how grasshoppers hear, 100 grasshoppers were used.

A loud noise was made next to each grasshopper– in each case, the grasshopper jumped.

The next step was to remove the hind legs of every single grasshopper.

When this was done the experiment was repeated – a loud noise was made next to each grasshopper.

This time, not one of the grasshoppers jumped – the results of the experiment were 100% consistent.

The experiment proved that grasshoppers hear through their hind legs.

The point being that data is neither good nor bad, it is just information.

Without a brain to interpret it correctly, it’s useless.

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.