In 1946, the head of a Unilever subsidiary had an idea.

Unilever produced 75% of the UK’s margarine, but fats were rationed due to war shortages.

At the same time, people in Africa were suffering due to lack of food and work.

Frank Samuel saw a way to solve both problems at once.

There were vast amounts of uncultivated land in Africa – we could use modern ideas and technology to grow crops where the natives couldn’t.

The new Labour government launched the Groundnut Scheme.

To grow groundnuts (what we call peanuts) on three million acres in Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania).

The groundnuts would provide 80,000 tons of oil a year for margarine; they would also provide income and training for Africans.

It was a win-win situation – everything the new Labour government could wish.

As a formality, they sent a team of scientists to check the soil and found it to be fertile.

That was all they needed to know.

The Groundnut Scheme was approved – it wasn’t thought necessary to test-farm a small area.

As MP Ian Mikado said: "One can learn nothing very valuable about farming 100,000 acres by digging up a cabbage patch."

Which was a shame.

Because, had they tested it first, they would have discovered the land was impenetrable.

Army bulldozers had to be shipped in from Canada and the Philippines to try to clear it.

They would also have discovered swarms of killer bees that incapacitated the drivers.

They would have discovered there were no suitable ports where heavy machinery could be unloaded.

Or railroads that could carry it, or roads that were suitable for it.

They would also have discovered that although the soil was fertile, when it rained, it turned to concrete when baked by the sun.

So the groundnuts, which grew underground, couldn’t be harvested.

But none of this was discovered because no-one wanted to discover it.

They believed that modern ideas and technology could solve anything.

So it was decided that the African workers should be organised into modern trade unions.

Trades unionists were sent from Britain to help with this.

And sure enough, within days of their arrival the African workers came out on strike.

The land was so hard to clear that within a year two-thirds of the tractors were unusable.

Only 7% of the land planned for cultivation was ever actually cleared.

Four thousand tons of seeds were sent, resulting in just 2,000 tons of groundnuts harvested.

The few crops that had been grown cost 600% of their value.

So, after four years, the government wrote the whole project off at a cost of £49m (the equivalent of £1.3bn today).

The Groundnut Scheme showed the flaw when belief overrides practicalities.

In marketing, the current belief is that having a higher purpose will benefit any brand.

So strong, so unquestioned, is this belief that purposes are grafted on to brands willy-nilly.

Family harmony, a strong community, hope for the future, education, world peace.

It doesn’t much matter what the higher purpose is or how it relates to the brand.

As long as it gives us a nice warm feeling.

Presumably it’s successful, because the awards schemes have a separate category for it.

(So at least it’s making money for someone.)

Like the Groundnut Scheme, when the numbers are in someone may even think to ask some basic questions.

Like whether it has any relevance to the ordinary people that actually buy the products.

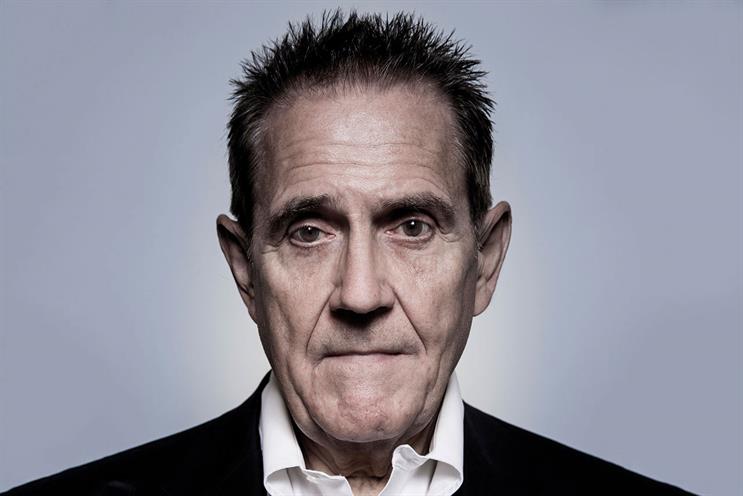

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.