The framing heuristic is an example of choice architecture and cognitive bias.

That sounds complicated but it isn’t.

Really, it’s just common sense – simple street smarts any salesperson knows.

Take Pepsi.

1959 was the height of the cold war between the US and the USSR.

The East and the West were totally closed to each other.

To thaw things out, the US held the American National Exhibition in Moscow.

Nikita Khrushchev was Soviet Premier and visited the exhibition.

It was July and hot, and he was sweating.

Donald M Kendall, Pepsi’s head of overseas operations, saw his opportunity.

In front of all the newsmen, he handed Khrushchev two paper cups of Pepsi.

He said one was from America, and one was made locally from Russian water.

He asked Khrushchev which he preferred.

Khrushchev sipped both, then predictably put down the American cup and finished the other.

He smiled and said: "Good Russian water better."

Kendall had the photograph and the quote he wanted: "Russian Premier likes Pepsi."

So, drinking Pepsi became almost a patriotic act.

Kendall used it to strike a deal to supply Pepsi to the USSR.

Pepsi not Coca-Cola – Coke remained forbidden.

In 1974, the first Pepsi plant was completed in Novorossiysk.

Russian currency wasn’t traded internationally, so they agreed to pay in vodka.

Pepsi became the sole importer of Stolichnaya into the US.

By 1989, Pepsi needed to expand from 26 plants in Russia to 50.

The deal was now worth $3bn a year, far too much to pay in vodka.

So, the USSR paid in ships instead: a cruiser, a destroyer, a frigate and 17 submarines.

For a short time, Pepsi became the sixth-largest naval power in the world.

Of course, it sold all the ships for scrap to get the money.

Pepsi, not Coke, supplied 275 million Russians who would take all they could make.

All because of the way Kendall asked that question to Khrushchev.

He didn’t give Khrushchev a single cup and ask: "Do you like Pepsi?"

Obviously, Khrushchev would have said: "Not as good as Russian drink."

He knew Khrushchev would have to say Russian was better, whatever question he asked.

So, Kendall gave him two cups and asked him: "Which Pepsi do you prefer: the American or the Russian one?"

Knowing he must choose the Russian one as superior, and of course he did.

That’s just salesmanship – set the choice up so that you get the answer you want.

It’s just common sense, street smarts.

But we can’t call it that – it doesn’t sound impressive enough for marketing people.

So, we have to call it the framing heuristic (it’s how you frame the question).

Or choice architecture (lead someone towards the outcome you want).

Or cognitive bias (set the choice up based on their known preference).

What was really smart was nobody but Kendall knew both cups were identical.

But it didn’t matter – Khrushchev had to pick whichever one Kendall said was Russian.

Instead of seeing a problem, he saw an opportunity.

And that’s creative thinking.

Whatever fancy name you give it, that’s how salesmanship works.

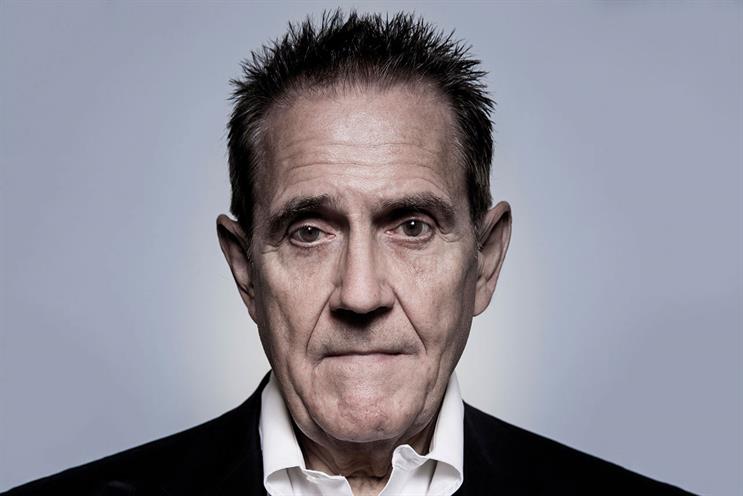

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.