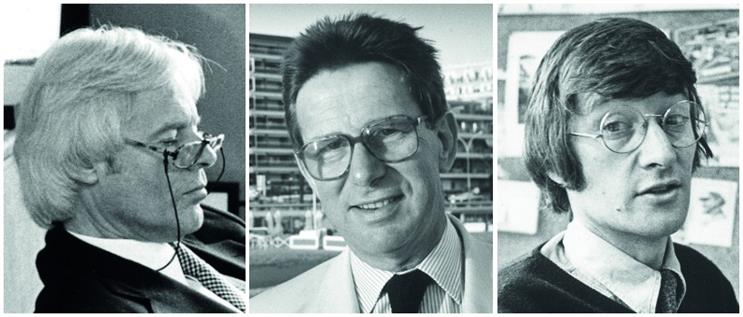

David Abbott

1938-2014

For many ad people, David Abbott was a god. It wasn’t just the white hair, the air of calm authority or his eloquence. At a time when advertising was synonymous with fast-lane lifestyles and dubious morals, Abbott was a beacon of integrity without seeming sanctimonious.

For many ad people, David Abbott was a god. It wasn’t just the white hair, the air of calm authority or his eloquence. At a time when advertising was synonymous with fast-lane lifestyles and dubious morals, Abbott was a beacon of integrity without seeming sanctimonious.

Abbott was about as far removed from the flashy, loudmouthed identikit adman as it’s possible to be. You’d never find him celebrating until dawn at an awards ceremony; he’d never be seen at a regular table at Le Caprice or The Ivy. Abbott Mead Vickers colleagues used to remark how much more comfortable he seemed in an unpretentious Greek restaurant on Marylebone High Street with a good book for company. In many ways, this was in keeping with his trademark elegant writing style.

Abbott sprang from a middle-class background. The son of a clothes-store owner in Shepherds Bush, he went to Oxford but quit after two terms to run the business after the death of his father.

His arrival in adland sparked a burning ambition to work for Doyle Dane Bernbach – no surprise, perhaps, given that Abbott’s style has often been compared to that of Bill Bernbach. Abbott was appointed managing director of DDB while still in his twenties.

When it came to setting up Abbott Mead Vickers with Peter Mead and Adrian Vickers, Abbott vowed that his new agency would be a humane place to work, not least because it made good commercial sense. "The 80s was a time when ad people thought they were more important than they really were," Abbott later said. "We tried to pursue a much quieter course."

So what is Abbott’s creative legacy? Undoubtedly there’s the mould-breaking work for Sainsbury’s, credited with turning the retailer from a cheap, downmarket chain to a grocer of choice for the middle classes.

Then there was the incisive poster campaign for The Economist, which has easily stood the test of time.

And what of the touching Yellow Pages campaign, Abbott’s riposte to those who claimed his literary style would never make the transition to television? JR Hartley, the pensioner who finds his out-of-print book on fly fishing, thanks to Yellow Pages, remains one of UK advertising’s most-remembered characters.

In a cynical and visual age, Abbott’s work stood out because of its craftsmanship and great storytelling: intelligent, honest and heartfelt.

Paul Arden

1940-2008

Bloody-minded, unconventional, exasperating, exuberant, Paul Arden was the eccentric genius who was Saatchi & Saatchi’s creative engine-driver during its most potent years.

Bloody-minded, unconventional, exasperating, exuberant, Paul Arden was the eccentric genius who was Saatchi & Saatchi’s creative engine-driver during its most potent years.

Small wonder that nobody who worked with and for Arden ever forgot the experience. He was both idolised and feared, and his maverick style made it hard to get the measure of him.

"What do we make of Paul Arden?" 北京赛车pk10 once asked. "Is he a talented eccentric who doesn’t know the meaning of the word conformity? Or is he merely the most pretentious man in the advertising business?"

If truth be told, he was a bit of both. Yet he was also the spark plug for some of the best work to come out of Charlotte Street. Silk Cut’s "Slashed purple", The Independent’s launch campaign, "It is. Are you?", the British Airways "Manhattan" spot and much more all appeared during Arden’s 14-year stewardship of the Saatchi creative department.

He never stopped searching for new and unusual ideas, and never shirked from refusing to give clients what they wanted if he thought it wasn’t right. "There is no distinctive style here," he once said of the agency. "If there was, we would put a stop to it immediately."

Arden wouldn’t stand for any slipshod work being presented to him. It would either be torn up or tossed to the floor, where he would stamp on it. He had no time for reputations and believed that creatives were only as good as their last idea. "Life with Paul was one long furious row," a former colleague recalled.

Once, when asked to give a presentation on creativity, he arrived on stage with a string quartet, which proceeded to play some Beethoven. He then walked off without saying a word.

He never lost his creative passion and was in his sixties when his self-help book It’s Not How Good You Are, It’s How Good You Want to Be was published. It sold more than 500,000 copies.

Until the end of his life Arden deplored convention. "Astonish me" was always his best advice. "Bear these words in mind," he once wrote, "and everything you do will be creative."

John Webster

1934-2006

John Webster was everything a creative titan wasn’t supposed to be. His steel-framed spectacles personified his studious manner; there was no hint of flamboyance either in his dress or demeanour. He never threw tantrums, could be painfully shy and never went to Cannes to collect any of the gold Lions that were showered on him.

John Webster was everything a creative titan wasn’t supposed to be. His steel-framed spectacles personified his studious manner; there was no hint of flamboyance either in his dress or demeanour. He never threw tantrums, could be painfully shy and never went to Cannes to collect any of the gold Lions that were showered on him.

It wasn’t that Boase Massimi Pollitt’s creative catalyst wasn’t aware of his talent. He just preferred not to shout about it. The originator of some of the most enduring British TV advertising of all time – from the Smash Martians and the Sugar Puffs Honey Monster to the Hofmeister Bear – Webster produced ads that not only bowled over awards juries but also that millions of people were happy to welcome into their homes. This is what mattered most to Webster.

It’s no accident that Webster’s creative prowess was at its height at a time when TV was delivering mass audiences. The two were made for each other.

So what was the secret of Webster’s success? Much of it came from being an astute observer of everyday life. He loved the films of Jacques Tati, saying: "He taught me that humour or irritation, for most people, comes not from large dramatic situations, but from normal ups and downs of life."

He was a voracious collector of the trifles that he thought might open up a creative route – from scraps of poetry to newspaper photographs.

The same was true of the movie and TV characters that he locked away in his mental filing system. The Honey Monster, for example, was a development of Cookie Bear whose antics drove the crooner Andy Williams to distraction during his 1970s TV series, while the Cresta Bear ("It’s frothy, man!") was based on the degenerate lawyer played by Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider.

Webster liked receiving awards but only because "they give me confidence", he once said. "When an account man wants to turn down my script, he thinks twice."

The letters from teachers asking whether their class could have a still from one of his ads, hearing people in the street shouting one of his slogans – these were the prizes Webster valued most.