Recently, I heard a New York journalist on the difference between sympathy and empathy.

When she was little, her dad let her choose her own Mother’s Day gift for the first time.

He took her to the mall and let her look around all the shops.

She was so excited, eventually she saw the gift she loved.

A box of different glittery, plastic jewellery: earrings, rings, bracelets, necklaces, tiaras.

Her mum tried on all the jewellery, even the tiara – and, of course, said she loved it.

But, of course, afterwards it was the little girl who wore it all.

Because the little girl knew about sympathy, but she didn’t yet know about empathy.

Sympathy is when we want other people to feel good, so we do whatever would make us feel good.

Empathy is when we put ourselves in the other person’s place.

When we try to understand what would make them feel good.

Sympathy is emotional, empathy is rational.

For empathy we have to think, not react.

That’s one of the first things I teach students.

They ask me what advertising I like.

I say: "If we’re professionals, we don’t use language like that."

The phrase "I like" has two things wrong with it: the pronoun and the verb.

First, the pronoun "I" suggests that what we think is important, and it isn’t.

We are not the market – therefore, it’s irrelevant at best.

Second, the verb "like" is subjective, and without rational judgment.

So we don’t use the terms "I like" or "I don’t like", they are only for consumers.

Professional language is "It works because…" or "It doesn’t work because…"

This forces us to discuss the function, what the job is, not just our subjective preference.

And it forces us to be objective, to give reasons, to think rather than react.

When I talked to David Abbott or John Webster about their ads, that’s how they spoke.

David could tell me why an ad was a DPS rather than a single page, or a 48-sheet rather than a 16-sheet, why he’d used Bodoni rather than Futura, why photography not illustration.

John told me why the commercial was black and white rather than colour, why it was silent rather than with music, why the set was oversize not lifesize, why the voiceover was American not English.

There was nothing random or subjective in their work, everything was there for a reason.

Consequently, absolutely every aspect of it was open to question.

Because every aspect could be explained logically.

In New York, it was the same with Bill Bernbach, Helmut Krone, Mary Wells, Ed McCabe.

This isn’t the world of fine art – in our world, form follows function.

We don’t decide what it looks like without reference to the job it’s doing.

That’s the difference between sympathy (emotional, subjective) and empathy (rational, objective).

That journalist ended her talk with another example: her cat.

To demonstrate how much her cat loves her, it keeps bringing her presents.

The most valuable thing that the cat can find to prove its love is a dead mouse that it’s hunted and killed.

Because that’s what the cat would love most.

Our advertising is like that dead mouse.

We love awards – awards make us happy so that’s the sort of advertising we try to do.

We never bother to see what people actually want.

Consequently, there are currently 615 million ad-blocking devices globally.

That’s $41.4bn revenue lost, and that’s predicted to rise to $75bn by 2020.

That’s the cost of giving people what we like, not what they like.

Sympathy not empathy.

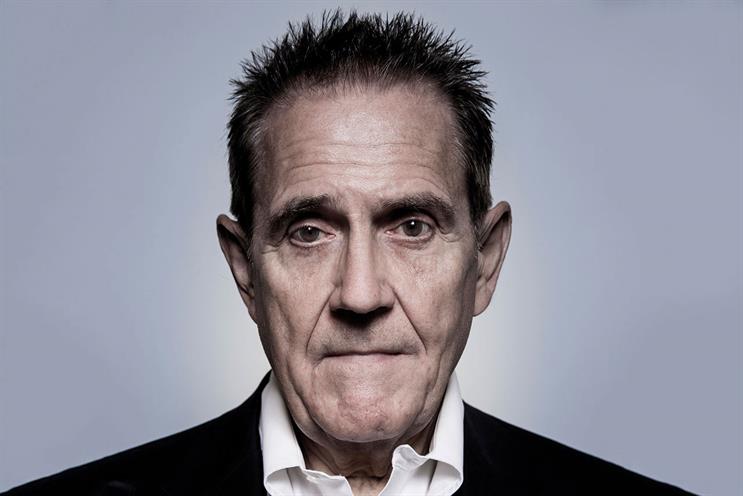

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.