Scotland is unique in that each family has its own patterned cloth called a tartan.

Each tartan is different and each family, or clan, can trace its heritage back a thousand years to the particular pattern it’s always worn.

Except they can’t.

It was all made up in 1829 by two brothers from Surrey.

Tartan patterns always existed, of course, but they had nothing to do with clans.

It was just whatever cloth was available to the people of a particular region.

The oldest example is in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh: a small scrap of wool, herringbone, tweedy cloth from around 300AD.

But it had no meaning, different Highlanders wore whatever cloth was available in their area, naturally people in different areas wove differing patterns.

And over the years tartan came to be known as a particularly Scottish Highland cloth.

Then, in 1822, the theatrical King George IV paid a state visit to Edinburgh.

He wanted to see tartan everywhere, as his fantasy of Scotland.

So suddenly every family wanted to own a tartan.

Seeing an opportunity, two brothers from Godalming in Surrey jumped at it.

They were born John and Charles Allen in Wales, but changed their name to the more Scottish-sounding Allan, then Hay Allan, then Hay, then finally Sobieski Stuart.

They published a book called Vestiarium Scoticum.

They said this book was copied from a document from 1721, which was itself a copy of a parchment from 1571, detailing the tartans worn by 75 different clans, from the Highlands, the Lowlands, and the Borders.

The book, and the brothers, were received with open arms by Scots nobility.

It meant everyone could tell exactly what tartan they were entitled to, and could proudly boast of their heritage by wearing it to formal gatherings.

The brothers were the toast of Scottish aristocracy, they were given wealth and land.

But not everyone was convinced.

One of the most famous Scotsmen, Sir Walter Scott, wrote that the book "sounded like a tartan weaver trying to drum up trade", and that "the idea of distinguishing clans by tartan is but a fashion of modern date", and that "no Lowlander ever wore a clan tartan".

But in 1832 Sir Walter Scott died and, with him out of the way, the brothers were able to release another book Costumes of the Clans and, in 1847, The Tales of the Century, in which they claimed to be the grandsons of Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Eventually, in 1895, The Glasgow Herald tracked down the supposed 1721 copy of the Vestiarium Scoticum.

The newspaper's chemist wrote "The document bore evidence of having been treated with some chemical agents in order to give the writing a more aged appearance than it is entitled to."

So, proof that it was a fake.

But none of that affected the "tradition" that the Sobieski Stuart brothers had started.

Even today, people with Scots ancestry come from all over the world to have their "clan tartan" made into a kilt in Edinburgh.

The need for a sense of belonging overrides facts and makes truth irrelevant.

As David Hume, another Scotsman, said: "Reason is the slave of the passions."

Which is a great lesson for us, and worth remembering.

Sometimes the answer lies in the product, sometimes the answer lies in the consumer.

And sometimes the consumer is more important than the product.

And an exciting lie is nearly always more attractive than a boring truth.

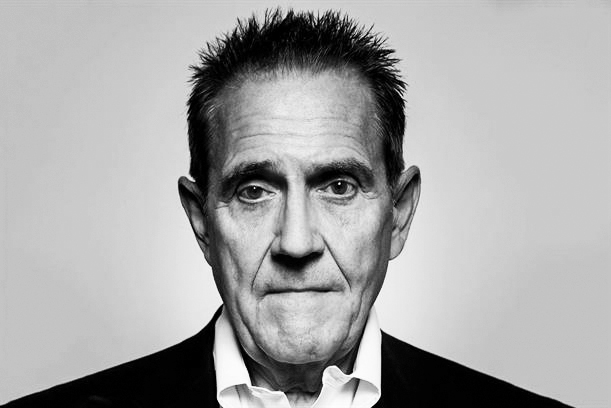

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Blindness and How to Cure It, Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three