The British are embarrassed to talk the way ordinary people talk, they think it's corny and patronising.

They like to flag their intelligence with long, complicated words.

But I was trained in New York and Americans aren’t embarrassed – quite the reverse.

They think it’s their job to talk like ordinary people, it’s more persuasive.

You might say Britain aspires to be white collar and America aspires to be blue collar.

A great example happened when Britain was at war and America was still neutral.

Most Americans wanted to stay out of the war.

The US agreed to sell Britain weapons, but that was as far as they wanted to go.

President Franklin D Roosevelt was sympathetic to Britain, but he had to tread carefully.

In 1940, Winston Churchill explained that Britain couldn’t afford to buy any more weapons.

He wrote: "The moment approaches when we shall no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and other supplies. While we will do our utmost, and shrink from no proper sacrifice to make payments across the Exchange, I believe you will agree that it would be wrong in principle and mutually disadvantageous in effect, if at the height of this struggle, Great Britain were to be divested of all saleable assets, so that after victory was won with our blood, civilisation saved, and the time gained for the United States to be fully armed against all eventualities, we should stand stripped to the bone. Such a course would not be in the moral or the economic interests of either of our countries."

The language was typically pompous, the way politicians feel they should speak.

Roosevelt replied in similar language: "There is absolutely no doubt in the minds of an overwhelming number of Americans that the best immediate defence of the United States is the success of Great Britain in defending itself; and that, therefore, quite aside from our historic and current interest in the survival of democracy, in the world as a whole, it is equally important from a selfish point of view of American defence, that we should do everything to help the British Empire to defend itself."

Roosevelt couldn’t help by simply "giving" Britain military aid, he had to find another way.

What he proposed was an arrangement whereby Britain could "borrow" the weapons they needed and either return them, or pay for them, after the war.

Such a thing had never been tried before – there was no legal precedent.

It would be both complicated and contentious to present the Lend-Lease bill to the US government.

So Roosevelt didn’t use bombastic, pretentious language, he spoke to human beings.

He said: "Suppose my neighbour’s house catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him put out his fire. Now what do I do? I don’t say to him, ‘Neighbour, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it.’ I don’t want $15 – I want my garden hose back after the fire is over. If it goes through the fire without any damage to it, he gives it back to me and thanks me very much for the use of it. But suppose it gets smashed up – holes in it during the fire; we don’t have too much formality about it, but I say to him, ‘I was glad to lend you that hose; I see I can’t use it any more, it’s all smashed up.’ He says, ‘All right, I will replace it.’ Now, if I get a nice new garden hose back, I am in pretty good shape."

Roosevelt spoke in what the British would call corny, patronising language.

But the Lend-Lease act was passed by 317 votes to 17 and the US lent Britain $50bn of military aid (equivalent to $700bn today).

Because instead of trying to use impressive language, Roosevelt spoke like a human being.

And that’s what Roosevelt can teach us about advertising.

That’s how we should be talking to people.

Because that’s what Bill Bernbach meant by: "Simple, timeless, human truths."

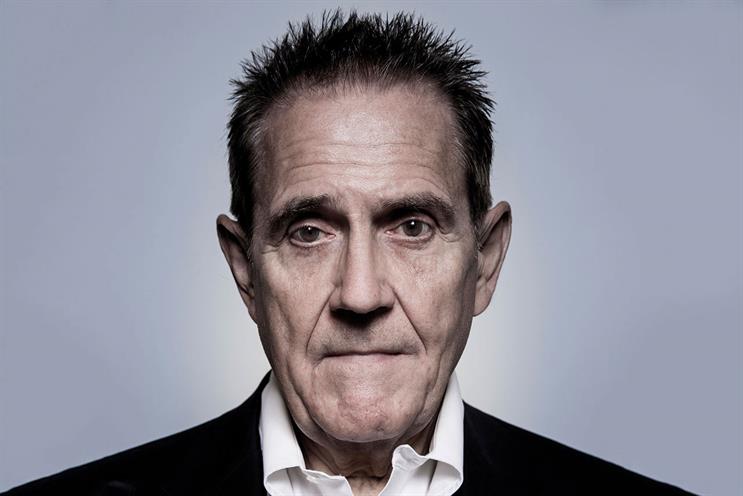

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Blindness and How to Cure It, Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three