Facebook hasn’t just pulled away from its rivals, it has rocketed into the social networking stratosphere.

With active users last officially recorded at 500 million and now thought to be more than 600 million, Facebook has become the unquestioned king of the social media sector, leaving MySpace and Bebo eating dust in its tracks.

But Facebook’s dizzying rise to dominance hasn’t stopped some observers wondering if it really will prove to be the last word in social networking, prompting potential rivals to look for an Achilles heel.

Take privacy, a regularly cited weak spot for Facebook. Critics have long argued that unless users apply the maximum settings, they can make themselves vulnerable to intrusion or unwanted attention from advertisers.

Facebook faced its first significant backlash on the issue in 2007 over the now discontinued Beacon targeted ad programme. The company’s drive to reassure users that it takes privacy seriously has seen successive policy tweaks, most recently in May. Settings are now arranged on a simplified "dashboard" aimed at giving users greater clarity and control over how much they share information.

And while Facebook can place ads according to general demographic data and any interests that users have explicitly registered in their profile, advertisers are not given any specific information about individuals or direct access to users.

But the company’s perceived slowness to deal with some of these concerns has given rivals an angle of attack. , tackles the issue head on. "Inherently private, Diaspora doesn’t make you wade through pages of settings and options just to keep your profile secure," the service’s homepage declares.

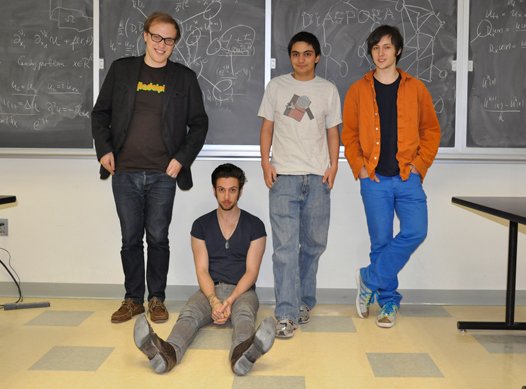

Still in development and expected to launch next year, Diaspora is the brainchild of four New York University students (pictured) who want to decentralise networking away from "hubs" like Facebook and give users "choice, ownership and simplicity".

And what about the quality of connections on Facebook, where ‘friends’ are often just casual acquaintances, even people you haven’t seen for years?

Less is more

Path, a network that launched last month as a photosharing app for the iPhone, addresses this concern. Co-founded by Napster founder Shawn Fanning and with a host of investors including Ashton Kutcher, the start-up expressly limits users to just 50 connections, compared to the Facebook average of 130.

Path’s creators took inspiration from Oxford University anthropologist Robin Dunbar’s theories about human interaction, which sets 50 friends as the outer boundary of our close personal networks, and 150 people as the maximum number of social relationships the human brain can handle at any given time.

Matt Van Horn, vp of business development for Path, which calls itself "The Personal Network", says: "Facebook is the most powerful network in the world and it’s an amazing tool we use every day. But it’s become more of an acquaintance network, for every person you went to high school with or worked with.

"If you are sharing with one person you don’t really trust or are not open with, that changes your sharing behaviour. We want to create an environment where users feel comfortable being themselves and can share their lives with people."

Path may develop into a text-based network, and is looking to make money from premium services and local advertising. But it’s hardly gunning for Facebook; Van Horn stresses it is "complementary" and has a "great relationship" with the all-conquering network, where its chief executive Dave Morin used to work.

When another ex-Facebooker, Chris Hughes, unveiled his new charity network Jumo last week, he also insisted it was no kind of rival to Facebook. It seems Facebook’s supremacy is starting to be taken for granted – it is something to be worked with, rather than against.

In fact, few experts would bet on new entrants giving Facebook anything worse than a fleabite. Richard Holway, chairman of TechMarketView, believes that, like Apple with iTunes, Facebook has cornered its market. "All my friends are on it and I’ve invested a huge amount of time in it over three years. It would take something absolutely startlingly different and wonderful to make me drop Facebook."

Making the web manageable

Ian Maude, internet analyst at Enders Analysis, points to Facebook’s colossal scale and rapidly growing financial muscle – he thinks revenues could climb to as much as $1.8bn this year, more than double last year’s performance – although he thinks some start-ups could work.

"You don’t have to be Facebook’s size to make money. The potential rewards are big enough to mean it’s worth trying even if the chances are relatively low, and venture capitalists will plough money in," he says. "But most of these things are, frankly, destined for the scrapheap – one or two may carve out a niche for themselves."

The author and social forecaster James Harkin argues in his forthcoming book Niche that there are two routes to success in the digital world: either to control an "ecosystem" or to preside over a tightly identifiable niche within that.

Harkin thinks Facebook works as an ecosystem. "It signs people up, in the end, because everyone is there. Facebook has 500 million users, and it’s possible to search for almost anyone there. Niche social networks are growing because they offer us the chance of what we all really want - which is to narrow down the web to a more manageable number of people."

Harkin believes the successful niches will be based on shared passions and interests. "They probably won't call themselves social networks, they might be dating agencies, magazines or fashion subcultures," he says.

"As new things grow up, there will be lots and lots of interesting new groupings and subcultures, many of which will be really exciting – and many of which people will be prepared to pay for."