Doug Ivester joined Coca-Cola as assistant controller and director of corporate auditing in 1979.

He was analytical, data-driven and a total believer in technology.

By 1999, he’d worked his way up to become CEO of Coca-Cola.

Fortune magazine wrote of him: "Ivester may give us a glimpse of the 21st-century CEO, who marshals data and manages people in a way no pre-information age executive ever did or could."

So, definitely a man who did things by numbers.

But numbers aren’t all there is to it when you’re dealing with people.

For instance, the law of supply and demand seemed basic common sense to Ivester.

The more people wanted something, the more they would pay more for it.

So it made sense to charge more for Coca-Cola in hot weather.

And, because he believed in technology, to use vending machines to change the price automatically.

In an interview, Ivester said: "I think it would be fair to raise the price of a soda on a summer day like today. Vending machines could be equipped with thermometers, and when demand for a cold soda rose with the temperature, the price would rise too. It’s just Economics 101."

That seemed basic economics to Ivester, but it seemed like something else to consumers.

It seemed like screwing the thirsty customer for every penny.

And the competition, Pepsi, made the most of the opportunity.

The Pepsi spokesman, Jeff Brown, said: "We believe that machines that raise prices in hot weather exploit consumers who live in warm climates. At Pepsi, we are focused on making it easier for consumers to buy a soft drink, not harder."

But because Ivester was an accountant, he was numbers-driven, not people-driven.

So he didn’t understand the emotional impact.

The share price of Coca-Cola’s bottlers dropped from $37 to $18 in five months.

And yet Ivester could have raised the price on Coca-Cola in hot weather, if only he’d understood people aren’t numbers.

If only he’d bothered understanding the price-anchoring effect.

Price-anchoring is an example of cognitive bias.

Don’t just present facts and figures, understand everything is judged in context.

So, the object of price-anchoring is to set up an initial price against which subsequent changes will be judged.

For instance, if the initial price is 50 cents, then raising it to 75 cents sounds expensive.

But if the initial price is $1, then cutting it to 75 cents sounds like a bargain.

Advertising people understand this, but accountants don’t.

To them, 75 cents is still 75 cents no matter what it’s compared with.

Ivester could have raised prices in hot weather if he’d presented it the other way round.

If he’d presented it as lowering prices in cold weather.

Just approach the law of supply and demand from a consumer perspective.

Lots of things are cheaper at times of low demand: airline fares, gas and electricity, hotels, railway fares, etc.

So presenting Coca-Cola temperature-controlled vending machines that way round would have seemed like a benefit to the customers.

Instead of an opportunity to gouge more money out of them.

Doug Ivester only lasted two years in the job of Coca-Cola CEO.

Because, while he was a brilliant accountant dealing with numbers, no-one taught him that consumers aren’t just numbers.

For consumers, 75 cents isn’t always 75 cents.

Depending on how it’s presented, 75 cents is a rip-off, or 75 cents is a bargain.

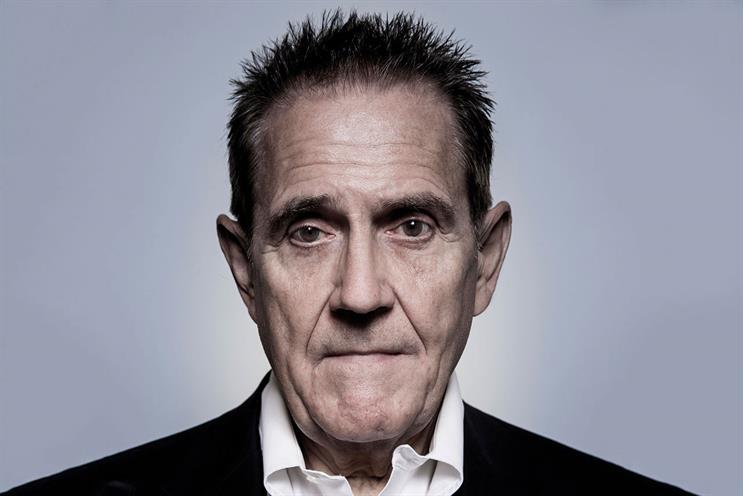

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.