This makes me curious.

Two words with dictionary definitions so similar that an alien skipping through Wikipedia would be forgiven for thinking them the same thing, yet engendering a reaction that could not be more different. Why?

Pre-testing involves the testing of broadcast work that has been through a few rounds of creative development just to get to that stage. Working hours have been spent, emotional investment made and – I don’t care how rock-like the emotional stability of an agency or client team – inviolate opinions formed about how it should be executed. This is because a broadcast ad is a linear, "closed" product, usually conceived and authored by no more than two people. It doesn’t develop or improve with use. The less that has to change, the more successful a pre-test is deemed to be.

A prototype, on the other hand, refers to a test model of a product or service, and that’s where the similarity with ad pre-testing abruptly ends. Designing something we hope people will want to use time and again demands we pay close attention to how every interaction works. It’s a calculatedly "open" process in several senses:

1 We stay open-minded about the outcome and, what’s more, we do so willingly. Even an early paper prototype of a digital service reveals opportunities and issues to work through that a concept cannot hope to illuminate on its own.

2 It’s a collaborative process by design. Rarely the output of a single auteur or a linear process, developing a product or service demands a set of various and complementary roles: a mix of interaction designer, producer, technologist, developer, writer and strategist, with a product-owner for goal-setting and sign-off.

3 It’s an iterative process that continues beyond first release. Prototyping may sound like it involves more process and thus bloats time and resource. Conversely, it can save time: we course-correct, rather than pursuing mistakes to completion, observing how users react intuitively to a product before the team’s own opinions calcify. "Make, test, learn, repeat" (words stolen from friends at Made by Many, the digital product innovation agency) is a mantra to work by, not a set of rules imposed by a third party with a set of predetermined norms.

Questions worth asking now

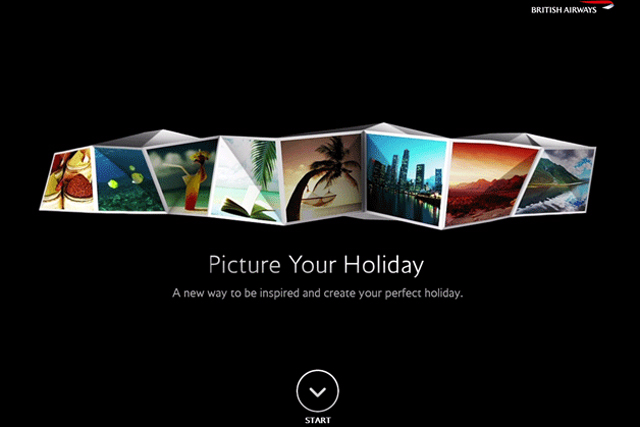

1 Are we prototyping to help sell in our idea within an organisation or as a part of the development process? Fine if the answer is yes to both. Even with a product like the British Airways "Picture Your Holiday" app (a BBH client), the soul of the idea was always in the interaction. Prototyping helped make that real from the start. With further prototyping, key interaction challenges were unearthed early and the team could explore how largely the same code base could be used across different platforms, leading to a more effective roll-out later.

2 Are we making a product or a message? Occasionally I get asked whether we should apply prototyping methodologies to broadcast creative. My answer is usually no, because unless a script is very complex or requires an animation process, the assets required for pre-testing don’t qualify as natural parts of the production process.

3 Is speed a competitive advantage in our market? If yes, then we have to ask: if we know our market, audience and brand and have trusted partners on board, what are we investing in pre-testing for?

By contrast, prototyping methodologies can make the work and the process faster, better, stronger – and, frankly, happier.