Marketers tied by contract to big, global communications agencies would traditionally harbour a secret yearning.

While the agency of record offered stability, scale and a certain comfortable rapport, the feeling was always present that, out there on the low-rent side of town, were younger, smarter offerings that the solus arrangement precluded – sexy starts-ups, fearless independents, agencies with thrillingly iconoclastic names, like Mother or St Luke’s.

Occasionally, a tryst would be arranged by a marketer either senior enough to cope with the fallout of breaking the rules, or junior enough not to care. A brief was quietly issued – usually something that the normal partner had struggled with for a while.

It was rare that these indiscretions led to successful fulfilment across the endless rounds of consumer research and Link testing. But the itch got scratched.

A new digital era

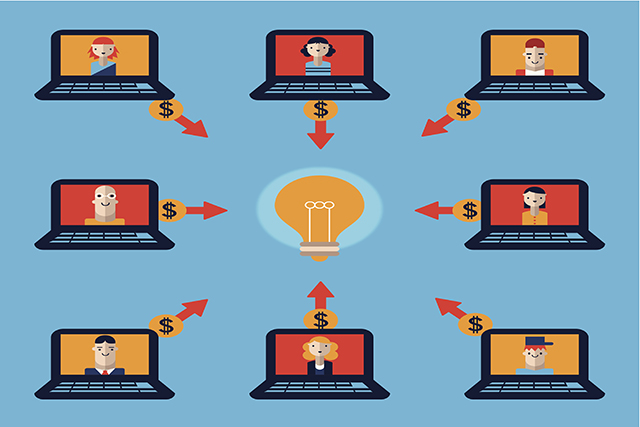

With the coming of digital connectivity, the same yearning took on a different guise. Never mind fresher agencies, out there was an entire world, a whole stratum of undiscovered genius with its fingers tantalisingly poised on the keys. Out there was a crowd.

Intermediaries sprang up to facilitate the new desire – the now defunct OpenAd at first, then Idea Bounty, and recently the more nuanced offerings of Tongal, Zooppa, GeniusRocket and Blur, which tend to focus on a niche area, such as video, or claim to "curate" their crowds.

Success stories are eagerly publicised – although, if you look closely, the same cases come up with suspicious regularity: TV ads for Danone yoghurt, Unilever’s Peperami, and Chevrolet, and various assignments for Pepsi, Pringles, Nokia and Gillette.

Commercial creativity is always about brilliance inside the box

Meanwhile, look at the Cannes winners over the past three years, and it is clear that the agency teams still dominate.

The crowd hasn’t shown up here yet. For all the creativity and freedom that the open internet fosters, for all the cleverness and wit that uploads itself onto YouTube every hour, very little

of it translates to the world of branded, commercial communications. Why?

The answer is that commercial creativity demands a skill set far rarer than pure imagination and a love of freedom. It demands two capabilities that pull cruelly against each other. First: brilliant, sweeping originality. Second: its polar opposite – tight, disciplined compliance.

Creativity

Brands are already highly organised constructs, long before the creative professional gets to work with them. The result is that commercial creativity is always about brilliance inside the box – one bounded on its six sides by the brief, the objective, the brand guidelines, the medium, its dimensions (either physical or temporal) and the budget – to say nothing of regulatory constraints. It takes an extraordinarily rare talent to come up with anything that simply covers the bases, let alone soars above it all to strike wonder into watching eyes.

The final episode in series 13 of Top Gear showed an entertaining glimpse of the difficulties. Jeremy Clarkson and James May attempted to create a 30-second TV ad for the Volkswagen Sirocco Diesel, presenting their ideas to DDB’s executive creative directors.

One script after another was felled for being off-brief, inappropriate, cliche´d or flagrantly in breach of regulations. The sequence was tongue-in-cheek, but it served to delineate the tiny space in which creative professionals must work their magic.

.jpg)

.jpeg)