For artist and producer Prince Rapid, the early days of grime were a time of inventiveness – not least when it came to the challenge posed by scaling the heights of inner-city tower blocks to mount radio aerials.

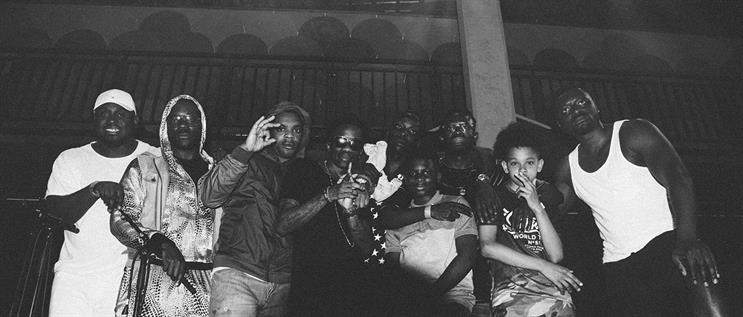

He was an original member of Ruff Sqwad (pictured above), a group formed 15 years ago in Bow, east London. It is now considered one of the key pioneers of grime music, a genre that emerged in the capital in the early 2000s and is influenced by garage, jungle and hip-hop.

In the early days, grime’s only outlet was pirate radio, which explains why Rapid – whose real name is Prince Owusu-Agyekum – and many of his friends found themselves setting up rooftop broadcast systems. Those were the lengths they would go to get their sounds heard.

You no longer have to tune in to pirate radio to listen to grime. Mykaell Riley, director of the Black Music Research Unit at the University of Westminster, worked on a recent study of the genre ("State of play: grime") commissioned by Ticketmaster. He describes grime as the most "significant musical development within the UK for decades".

So, as grime goes mainstream, commercial opportunities have inevitably followed, and brands as varied as Adidas and HSBC have used it in their marketing. Just last month, grime posterboy Skepta – winner of the 2016 Mercury Prize, UK popular music’s most prestigious award – starred in Nike’s triumphant viral ad "Nothing beats a Londoner".

Nike’s agency, Wieden & Kennedy London, said Skepta was chosen for the video precisely because he is something of a hero to many young Londoners.

This wave of brand interest is testament to grime’s growing influence. But the relationship between marketers and subcultures is rarely an easy one. "A bit like punk in the 1970s, grime is the sound of anti-establishment youth," says Henry Scotland, managing partner of Iris, which has worked with grime musicians for brands including Superdry and Adidas.

"Unless the brand already plays some role in youth or street culture, there’s a real risk of appearing to appropriate a subculture they have no permission to play with."

Owusu-Agyekum himself fronted an ad campaign by BMB for soft-drinks brand KA, when it held a competition last September to discover the best emerging grime artist in the UK. The winner, Birmingham rapper Lady Sanity, was rewarded with an artist-development package and recognised at The KA and GRM Daily Rated Awards, a grime industry ceremony.

Owusu-Agyekum’s collaboration with KA Drinks made sense because he grew up drinking its products, he says. The company was also already involved in the grime community, having co-created and sponsored the Rated Awards for two years.

Value exchange

That kind of authenticity was also evident in Adidas’ 2016 collaboration with grime MC Stormzy, who provided a soundtrack to mark footballer Paul Pogba’s transfer from Juventus to Manchester United. The pair are mutual admirers and from a similar background, says Gareth Leeding, creative director of We Are Social Sport, the agency behind the campaign.

"The value exchange was right for both the talent involved and the brand. It felt authentic and because of that everyone came out on top together," Leeding says of the work. "It needs to be a collaboration to make sure both sides are happy and [the work is] authentic to what they would normally do."

It also helps if the brand and artist have a "shared level of cool", Leeding adds. That was certainly the case with Nike and Skepta. The brand had the credibility to form the partnership because it is seen as "cool", and many grime artists sport its footwear, Wieden & Kennedy London creative director Mark Shanley, who worked on the ad, says.

"We tried to do it sensitively, to hold up a mirror to this subculture and celebrate it, as opposed to just sticking a swoosh at the end of the video and saying we’re down with that," Shanley adds. "You can’t just stick your logo at the end of a grime video and say you’re a cool brand."

Skepta starred in Nike's 'Nothing beats a Londoner' ad

Owusu-Agyekum believes grime, which is still seen primarily as a UK genre, will one day enjoy worldwide popularity. With artists such as Skepta and Stormzy, who won best male solo artist and best album at the 2018 Brit Awards, enjoying mainstream success, more brands will warm to the prospect of collaborating with the grime scene, Scotland predicts.

Indeed, according to Leeding, more progressive brands have always looked to subcultures to grow and find new audiences. "Subcultures are where new and interesting things are being created. It’s a place for creatives to be inspired," he explains. "When you can capture that raw energy that exists in subcultures, you can breathe new life into a brand, genre or concept."

Marketers’ increasing attraction to grime is a reflection of the natural creativity within that genre, Leeding adds. As Owusu-Agyekum puts it, grime "wasn’t taught, it was fresh music".

Selling out?

Subcultures might inject fresh creative energy into a brand, but what of the artist? Are cutting-edge musicians "selling out" by lending their talent to advertisers?

"Only if the sole value being exchanged is money," Scotland says. "But most deals these days see artists benefiting enormously from the strength of the creative, the timing and the distribution."

For Owusu-Agyekum, the question of compromising artistic credibility depends on whether an artist is forced to alter the style that garnered them attention in the first place.

"When you get more mainstream and become a bigger success, a lot of people change their approach and content, and start making more popular sounds," he cautions. "When acts become too commercial, it changes how the music is seen in the streets."

However, Owusu-Agyekum acknowledges the financial lure is a potent factor. "If it puts money in people’s pockets, I’m happy about that," he says.

Prince Rapid

While he has seen some of his peers benefit from commercially fruitful deals, it remains a rarity on the grime scene. For less popular artists, brand partnerships can provide real creative support in a shifting music industry, where falling record sales have taken their toll.

Marketers that want to get involved must "make sure to provide a positive platform for that subculture to express themselves", Leeding warns. "They need to have long-term aspirations in that community. There’s nothing worse than when you see a brand dipping their toes in that subculture and it’s just a one-off. It’s almost better to have done nothing at all."

Owusu-Agyekum urges brands to "know our journey, where [grime] comes from, and what artists had to do to get to this stage". As his memories of climbing tower blocks illustrates, grime originated among London’s youth as a DIY genre. He and his friends – whom he characterises as "mischievous" – experimented with sounds in their bedrooms, making music, instead of following the criminal examples of some "elders", as Owusu-Agyekum describes them, in their community. They didn’t wait around for record deals to create something.

So, what if marketers nurtured that DIY spirit?

Stormzy wasn’t a big name when Adidas first worked with him; neither was Abra Cadabra when the company chose him to create a custom track for an ad with Spurs footballer Dele Alli last year.

As the music industry changes, perhaps brands could provide a different channel for musicians to share their work, Leeding says.

"Why can’t brands reinvent the record label?" he asks. "If you can go on a journey with an artist over a period of 10 years – just before they’re about to break onto the scene to becoming a globally known artist – that could be much more valuable."

Owusu-Agyekum says his life changed when he gained access to the music industry, and now he is trying to pay it forward. He has set up a mentorship organisation, New Build Creative Resources, which aims to educate marginalised young people about the industry and introduce them to creative careers.

"A lot of young people think they can only be MCs or producers. Not everybody can be a rapper, but they don’t realise there are so many jobs within one industry. You could be a manager, a marketer, study law, become a publisher," Owusu-Agyekum says. "We’re finding talent and pushing them into the light."

It is also why KA Drinks’ competition to find emerging grime artists was close to his heart. Owusu-Agyekum recognises that talent can come from anywhere – from Ghana to the streets of east London or a teenager’s bedroom. And when looking for that spark – the same one that many creative marketers seek – he sticks to a principle that brands could mirror.

"You have to say something that grabs people’s attention," he says. "How can you change the way you look at things? How can you empower people?"