In 1879, a Scotsman, James Murray, began to compile theOxford English Dictionary.

The project was simple but vast: to list every single word in the English language.

Not just the top few thousand, but absolutely every word, however obscure.

And not just the meaning, but when it first appeared and when it was modified.

This was an insane project, almost beyond comprehension.

It meant reading every book ever published in English, every word however esoteric.

The problem was they could never afford the enormous amount of manpower needed.

So, in 1879, Murray invented crowdsourcing.

He printed a four-page leaflet appealing for volunteer readers.

He sent it to newspapers and magazines in Britain, the US and the colonies.

He even sent it to bookshops to insert in books, and to display on their counters.

He asked readers to note words, what they meant and where they’d first appeared.

He was inundated with replies, eventually six million contributions.

The work took forever (eventually 70 years); each letter took several years.

Murray became dispirited, how could such an insane task ever be complete?

But suddenly, in 1881 he began to receive replies in the post from Dr WC Minor.

In each parcel came hundreds of definitions with information about where each word had first appeared, some going back hundreds of years.

The amount of work, the clarity and attention to detail was astonishing.

Only a rich, cultured, learned man with a lot of time on his hands could perform this task.

Over the years Dr Minor’s contributions came in their thousands.

In a preface to an early volume of the dictionary, Murray expressed his gratitude:

"Invaluable in enhancing our illustration of the literary history of individual words, phrases, and constructions have been the unflagging services of Dr WC Minor, which have week by week supplied additional quotations for the words actually preparing for press."

By 1889, Murray and Dr Minor had been corresponding for eight years without meeting.

One day, Dr Justin Windsor, Librarian of Harvard, remarked to Murray: "You have given great pleasure to many Americans by speaking as you do in your preface of poor Dr Minor. This is a very painful case."

Murray asked what could be the problem for such a cultivated, educated man?

Dr Windsor was amazed he didn’t know.

He explained that Dr Minor was a patient at Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

He was an American who shot and murdered an innocent man in London, whom he believed was one of a gang who came up through the floorboards at night and sexually abused him.

Dr Minor was quite insane.

It became apparent that it was his insanity that made him perfectly suited for the project.

He was cultured, educated, obsessive, fixated, with nothing but time on his hands.

Because he had a pension from the US Army and nothing to spend it on, he had fitted out his cell like a library complete with every book ever written in English.

His every waking minute was consumed by obsessive reading and notations.

The dictionary became his life.

The insane project might never have got finished without his insane contribution.

And yet if Murray had known about Dr Minor, he might have refused his help.

He might not have allowed a madman anywhere near such a scholarly work.

In which case we might not have the Oxford English Dictionary today.

Which is proof of something I learned early on in my career.

In England, we are too often seduced by either posh accents or fancy job titles.

But the quality of an idea doesn’t depend on the source: strategists, marketing or creatives.

You should judge the idea on its own, not by where it came from.

A good idea doesn’t care who has it.

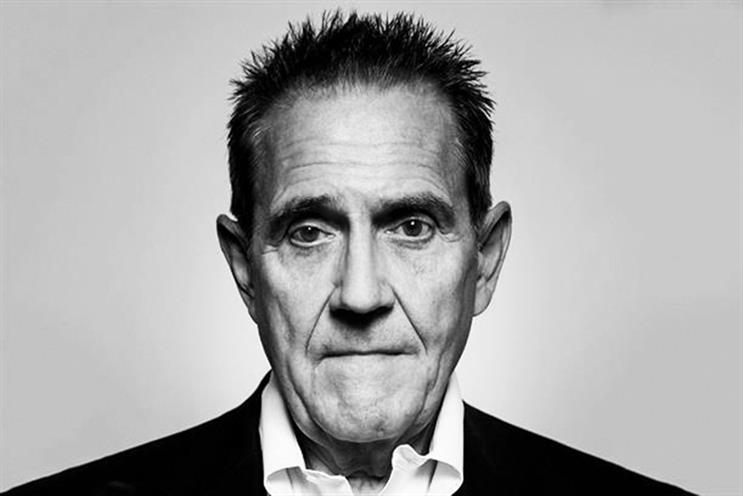

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Blindness and How to Cure It, Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three