In 1896, the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad, known as the "KT" (or Katy) for short was in financial trouble.

William Crush was responsible for attracting passengers and freight, he needed to increase sales and awareness, fast.

But in Texas in 1896, there was no media to advertise in: no movies, no TV, no radio.

So Crush needed to come up with a way to do two things in a hurry:

- Get a lot of free publicity for the Katy.

- Get people to quickly spend a lot more money on railroad tickets.

He grew up in Iowa along the railway tracks and as a boy often wondered what would happen if two trains ran into each other:

"I believed that somewhere in the make-up of every normal person there lurks the suppressed desire to smash things up. So I was convinced that thousands of others would be just as curious as I was to see what actually would take place when two speeding locomotives came together."

And that was his plan: two obsolete 35-tonne steam trains crashing head on into each other at 50mph, a combined speed of 100mph.

Of course, he couldn’t say that, he had to call it a "scientific experiment designed to study railroad safety".

The management of the Katy built several miles of track 15 miles north of Waco, Texas.

Entry was free, but there were no roads, the only way to get there was by train.

Fares from across Texas were priced at $2 from Austin, up to $3.50 from Houston (that’s $60 and $105 in today’s money).

If the predicted 20,000 people travelled to see it, the Katy would make a lot of money.

In the event, 40,000 turned up and the event was a massive success.

Well almost.

One reporter wrote of the crash: "The immense crowd was paralysed with apprehension.

"There was a swift instance of silence, and then, as if controlled by a single impulse, both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half a driving wheel."

A Civil War veteran who was there said it was more terrifying than the Battle of Gettysburg.

Three people were killed and dozens were maimed.

Photographer Jarvis Deane was struck in the eye by a bolt, and blinded.

(Doctors said he was lucky, the bolt snagged on his eye socket preventing it from becoming lodged in his brain.)

As you’d expect, the management of the Katy fired Crush immediately.

But then a strange thing happened.

The train crash made a massive profit and was covered by every newspaper in the US.

Suddenly the Katy was the most famous railroad in the country.

So, the next day they hired Crush back.

In fact, New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis now wanted their own train crashes.

It seemed the US couldn’t get enough head-on locomotive wrecks.

In fact, until the 1930s, crashing railroad trains became one of the biggest entertainments in the US, with over 146 train wrecks.

We may look down our noses at train wrecks as a popular form of entertainment.

And as far as train wrecks for advertising, what even is the brand purpose?

But for four decades train wrecks were amazingly successful.

Because people don’t want to be lectured about what they should like.

People don’t want advertising administered like taking medicine.

People just want fun.

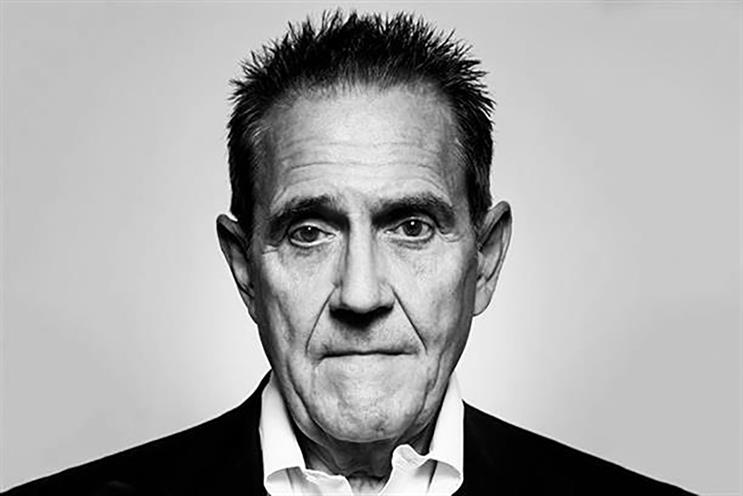

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Blindness and How to Cure It, Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three