In September 2006, we were sure Generation Free, the ABC1 18 to 35-year-olds who have grown up with the internet but without a newspaper-buying habit, would embrace us.

Before launching thelondonpaper, our research among Generation Free revealed that the number one activity they admitted to on their evening Tube journey was to stare blankly into space.

They told us they would read a paper if it gave them something they wanted in an attractive format, it was easy to digest after an exhausting day, it wasn't pompous or didactic, it entertained and informed, and it shared their love of living London life to the full. In the internet age, they were just not going to pay for it any longer. And Metro had already made free papers respectable.

Most of our audience can afford to buy a newspaper. But they are not prepared to commit the time or the effort to the transaction process and, largely, see no need to. We decided to go to them, using a mobile, flexible distribution force.

Very quickly, more than a million readers a day were interacting with thelondonpaper, eagerly consuming our easily digestible mix of the serious and the not so serious.

They started to contribute reader model applications, opinion columns, Lovestruck dating messages and Pet of the Day photographs with equal relish. We dare not change any of our regular features without canvassing our readers' passionate views on the matter.

For Generation Free, price-free media is not without value or "cheap". Our readers, and the users of Google, Skype and Facebook, all have extremely high expectations of our service, regardless of the fact they are not paying for it.

This trend is challenging and forces responsibility upon us. And rightly so, because Generation Free's crucial transaction is not money, but time.

Stefano Hatfield, editor. Thelondonpaper

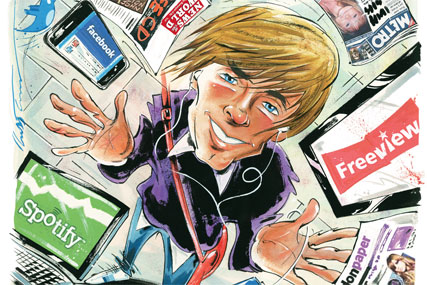

It seems hard to believe, but none of the following everyday brands - Facebook, BBC iPlayer, Spotify, thelondonpaper, Twitter - existed in the UK before 2006.

Not only have these successful upstarts crashed their way into the modern consumer's lifestyle, but they are the first generation of media brands to offer their services for free.

And, radically, free no longer equates to cheap, with modern consumers expecting a "freemium" service in a beautifully designed, well-considered package.

This radical generational change started with consumers under 35 who grew up with the internet, but is catching on fast among an older audience of "early adopters", who similarly expect high-quality information and entertainment without paying a penny.

Mike Soutar, chief executive of ShortList Media, says: "We are in the middle of a complete revolution. It started with consumers, it is sweeping all before it, and the smart media owners and brands are not waiting around to take advantage of it."

The good news for advertisers is that free consumers are sophisticated creatures, who understand that the "price" of engaging with free media is that it is advertising-funded.

Furthermore, there is no link between engagement and price; consumers are absorbed by content that is relevant to them and is presented well.

The interesting question is whether media owners - particularly in the digital space - will ever be able to put the free genie back in the bottle. Can they ever start to make significant money from - even, heaven forbid, charge for - products they have so far given away for nothing?

Soutar believes not. He says: "Free media is changing the old, incumbent order, and the change is so far-reaching that most people can't see how momentous this shift will be.

"Media owners who are hoping the old order will somehow reassert itself are burying their heads in the sand."

Harriet Dennys, features editor, Media Week