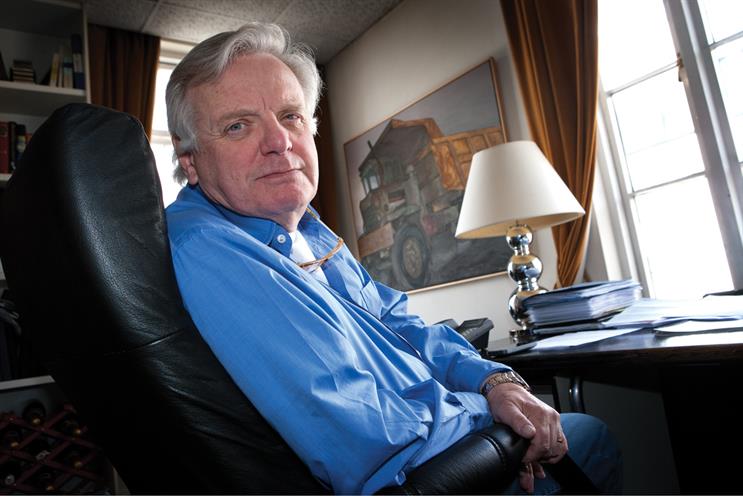

It was one of the few spring days that actually felt like spring when 北京赛车pk10 met up with the legendary TV impresario Lord Grade. The sun shone brightly into his compact King’s Road offices and Grade was in high spirits as he fidgeted with his iPad – he was planning to use it to watch cricket when the interview was over.

The previous day, Pinewood Shepperton studios – which Grade chairs – had its £200 million expansion plan blocked by the local authority, South Buckinghamshire Council, which deemed the development "inappropriate". Grade seemed to be taking the news in his stride, though, and showed no trace of bitterness. He admitted finding the process frustrating but was sanguine about the studio’s appeal prospects. Presumably, more than 40 years in the TV and film industry gives a man perspective on these matters.

However, when you get Grade on to the subject of film trailers, it’s a different story, and the sanguinity disappears.

"Cinema trailers are the worst kind of marketing," he seethes. "They have no faith in the intelligence of the audience. It’s just crash, bang, wallop. Why not just stop and let people talk for a second?"

Grade has seen a lot during his career in TV and film, which has taken him from London Weekend Television, to the BBC, to Channel 4 and ITV – not to mention a stint in Hollywood. The man is no stranger to criticism either, taking flack for many of his programming decisions. But it is impossible to deny that Grade knows a thing or two about the arts and show business. And, as his outburst on trailers showed, he is also a man who remains passionate about creativity.

What does commercial creativity mean to you?

Creativity is creativity, whether it’s commercial, public sector or whatever. I suppose commercial creativity is where you are working to a brief, but that shouldn’t inhibit the imagination. Some of history’s greatest artists and composers worked to a brief, which is what creatives do in agencies. For some artists, their commissioning patron is their own inspiration, but you have to be in a pretty good position to do that.

Do you think the British creative industries are in good shape?

Oh yes, very much so. Whether you’re talking art, architecture or movie-making, we’re very strong. Where we have been a bit lacking is in invention. Well, we have been brilliant at inventing things, but absolutely crap at turning them into commercial opportunities. We don’t like selling in this country – salesman is a term of abuse – but we’re all salesman now, ever since the Thatcher revolution.

Has anyone shaped your view of commercial creativity?

I was quite impressed with my uncle Lew’s [Grade, the media impresario] amazing ability to back his instincts. Nine times out of ten he was right, whether it was with Thunderbirds, The Adventures Of Robin Hood back in the 50s, or right through to The Muppet Show. He backed his instincts, picked good people and let them get on with it, and that has been my yardstick as well.

My first mentor in the business was a man called Billy Marsh who was, alongside my dad, the best agent in London – or even in Europe. He discovered Morecambe & Wise and Norman Wisdom, and was a genius. I was apprenticed to him when I was young. His sensibilities and understanding of creative artists were a fantastic grounding for me.

What inspires you?

Seeing a great performer, whether it’s on the musical stage or in the theatre – that, to me, is as good as it gets. I love to be in the theatre with 1,000 people, all sharing an amazing performance and seeing someone truly great. I get very moved by ovations – real ovations, not the first-night clack with friends and family. You can’t beat that. It’s better than a movie, and I love movies.

Do you think new technologies have come at a cost to creativity?

Not at a cost to creativity, but it’s a cost to investment. At some point, someone has to pay for the next generation of content and that’s what worries me. Look what’s happened to the music industry. It’s been wiped out, really. Where’s the money going to come from for the next Dark Side Of The Moon or Sgt Pepper? That’s the threat. Copyright is no longer respected.

Do you think new technology has made it harder to keep an audience’s attention?

Attention span is always going to be a problem. My attention span has shortened considerably, but I still like Test cricket… explain?

On the other hand, there is always a plus, and the plus is that anyone can be an artist today. You can shoot video on your phone. It’s wonderful. In the old days, anyone could get a paintbrush and start daubing and now we have the video equivalent of that. I think that will reseed the creative beds brilliantly.

How do you tell whether a creative idea will succeed?

I have an infallible test of creativity that, now that I’m no longer in the business, I can divulge. When anybody came to me to pitch an idea – be it a writer, producer or executive – I would try to change it.

I’d say: "It’s great but, instead of being a solicitor, could he be a doctor?" If they said "That’s a good idea", you know you’re in trouble because they’ve got no vision.

How healthy is the UK ad industry?

It goes through good spells and bad spells – I don’t think it’s a bad period at the moment – but I think where creativity is now at a premium is in inventing. There’s so much noise competing for people’s attention, so the real creativity now is in how we can market in a new way and use new technology to cut through this.

I do worry that the magic of creativity is going, however. The CGI stuff is brilliant, but the impact has gone because you know how it’s done. It’s all very cleverly done but, in the end, you can do so much with digital it’s like the audience is seeing how the magician did his trick. If I was creating any ad – which, gladly, I never have because I would be crap at it – I’d want to do it for real and shoot it in a way that people know it’s real.

[At this point, Grade refers to the Ford B-MAX ad, where a man dives from a high board through the middle of a car, as an example of a piece of creativity where the magic is spoiled by knowing the spectacle was created by computers. Investigation later revealed that the stunt was performed live by the stuntman Bobby Holland Hanton, who was on a wire but nonetheless dived through the car at 85 per cent of the speed of a regular dive.]

Where do you stand on the recent debate surrounding the restrictions on political advertising in the UK?

I don’t see why political parties shouldn’t be free to advertise as long as it’s clearly labelled as advertising. Let the people decide. If they don’t want to watch it, it will die. It’s a free market. I mean, come on, guys, get real! America seems to have survived.

TV advertising has stayed strong despite more people migrating to digital formats. Why do you think that is?

You can’t get the impact that you can get on mass television anywhere else. People are experimenting below the line and all that comes out of the same budget as TV, so it’s tough out there, but TV is very resilient. And the price is artificially low because of the ridiculous regulatory regime.

Have you embraced new technologies and social media?

I’m not on social media and I don’t Tweet. People have heard enough from me over the years. But I’ve got a smartphone and I have an iPad.

How important are the creative industries to the UK?

They’re vital. I’ve heard successive prime ministers talk about the three growth sectors of the economy – financial services, the public sector and the creative industries – and I think the creative industries are the last man standing in that trio. We’re so good at it. I look back to when I was a teenager in the late 50s. If you told me then that we were going to have some of the world’s leading chefs, fashion designers, artists… it’s gobsmacking. You couldn’t get a decent meal in London in those days. There wasn’t a chef worthy of the name.

Do you subscribe to the view that there is more creative output in an economic downturn?

It’s always there, but it just becomes much more important.

How much of Pinewood Shepperton studios’ revenue comes from letting space to advertisers?

It’s a very small percentage. We just haven’t got the space. They’re always welcome, but do you take a three-day booking for an ad or a six-month booking for a film? Where we do very well with advertisers is that we have a custom-made water tank where advertisers do a lot of work. It’s 20 feet of clear, warm water with plenty of spots for cameras.

Do you think the Government is doing enough to support the industry?

’m a great believer in governments getting out of the way. The film industry, particularly, has been very well-served by this government and the previous government, no question about that. If we had more money, we would put more money into the arts, but we don’t have the money at the moment.