Beauty advertising has been successfully selling female consumers "hope in a jar for generations" but it is a strategy that is long past its sell-by date.

Take the visceral reaction to beauty and fashion icon earlier this month. Kardashian removed the Instagram after a swift and furious social media backlash.

Beauty advertising has traditionally been one of the worst offenders for embellishing reality and selling women idealised and restrictive forms of perfection, underpinned by extreme airbrushing and dubious claims.

However, recently, the big trend in beauty has been for hyper realness, with diverse models, bold statements of ’no-airbushing’ and simplified and playful product packaging. A shift reflected by new beauty players such as Crayola coming into the market promising to put the fun back into beauty.

But are brands right to jump on this bandwagon, or could they be damaging an industry that built its very foundations on fabricated aspirations and the promise afforded by "hope in a jar"?

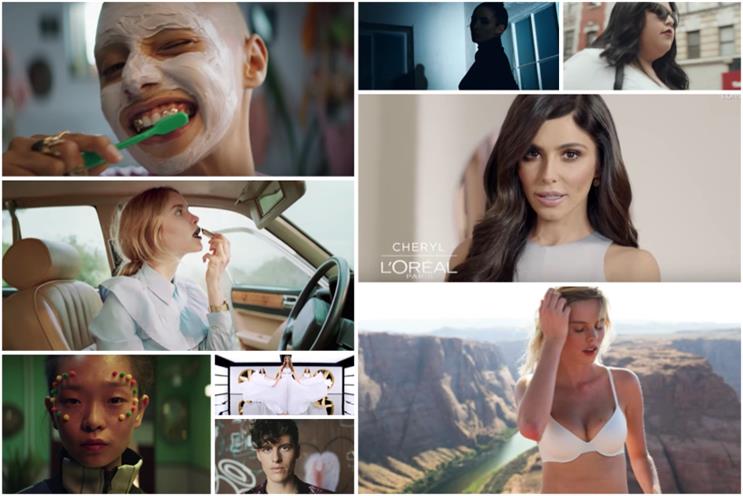

The creative agency Brave recently tested women’s emotional reactions to 10 fashion and beauty ads; some of which employed conventional approaches and others which embraced a more inclusive version of ‘realness’. We caught up with Sophie Russell, a senior planner at Brave to find out what the implications of the research is for brands.

Q: Why are consumers rejecting 'fake' beauty ads?

A: There are two primary drivers. The first is ‘perfection fatigue’ - consumers are so accustomed to seeing the conventionally ‘fake’ and perfectly polished beauty ads that the primary response is simply indifference. They are increasingly aware of advertising tricks and techniques, and are instantly sceptical that they will be able to achieve the same look at home – without the crowd of stylists, makeup artists and image retouchers.

The second is a more active rejection. The #bodypositivity movement is empowering women to rebel against narrow and unattainable beauty standards and instead celebrate their differences and their imperfections. As a result, brands casting only young, thin, white, flawless models no longer feel relevant in the modern age.

Q: The beauty industry has been selling 'hope in a jar' for decades what's changed?

A: ‘Hope in a jar’ is still alive and well, with the beauty industry growing at 5% a year globally - what’s changed is how women ‘hope’ to look. We are experiencing an inversion of influence; in the past women primarily aspired to look like models and celebrities, now they are inspired by the beautiful women of all shapes and sizes in their social media feeds.

Competitive pressure is also at play. The fashion and beauty categories have been shaken up in the last few years by new collaborative, transparent and ‘real’ brands like Glossier and The Ordinary. Traditional brands, fearful of losing share, are having to change and adapt in order to survive in this new consumer-led world

Q: What are the key findings from your research?

A: On the whole, the ‘real’ ads performed better than the ‘fake’ ones, in both facial coding (measuring engagement through facial expressions) and galvanic skin response (measuring emotional arousal through our sweat glands). Worryingly, brands adopting conventional beauty approaches achieved some of the lowest scores we have ever seen using the tool, proving the indifference hypothesis correct for this category at least.

However, this is not to say all of the ‘real’ ads scored fantastically. Some of the brands who had fully embraced the trend within their creative, by challenging stereotypes and celebrating individuality, achieved high scores (Aerie, H&M, Dove, Asos beauty), while others who had only nodded to the trend failed to see much emotional uplift at all (Rimmel, L’Oréal Elvive).

It seems that realness is not something brands can adopt half-heartedly.

Q: What resonates with consumers and why ?

A: Body positivity: "Real me" by Aerie and "My beauty, my say" by Dove both explicitly championed body positivity and, as a result, were rewarded with high engagement and emotional intensity throughout.

Diversity: We frequently saw peaks in engagement where diverse cast were shown – for example the men in the Asos beauty ad, the older woman in the H&M ad, and when plus-size women were seen for the first time in the Aerie ad.

Strong women: We saw peaks in engagement where women were shown in powerful positions such as leading a board meeting in the H&M ad, or when the boxer in the Dove ad states: "My face has nothing to do with my boxing".

Q: What is being rejected and why?

A: Unattainable aspiration: The ads which relied on the traditional aspiration of perfectly polished, glossy women on a whole received very low scores. Interestingly, we saw the same indifference whether a model (Pantene), celebrity (L’Oréal Casting Creme Gloss) or influencers (L’Oréal Elvive) were used.

Exaggerated product claims and demonstrations: We saw large peaks in contempt (measured by facial coding), during an airbrushed ‘before and after’ of the effect of Maybelline’s mascara, and when Olay posed the question of the beautiful model: ‘Is it genes or is it Olay?’.

Inauthenticity: The Rimmel ad was very diverse and aimed to champion individuality, but unfortunately experienced decreasing levels of emotional intensity throughout. It seems the ad didn’t go far enough to make the mission feel true to the brand, and therefore struggled to really connect with the viewer.

Q: Is there a risk that far from being authentic 'real women' are seen as a marketing gimmick?

A: In short, yes. Our results tell us that consumers are already becoming indifferent to markers of realness, likely because so many brands have now jumped onto the bandwagon.

Consumers have caught on to the fact that for many brands, this shift towards realness is inauthentic and tokenistic, and only respond emotionally to ads which feel genuine and credible. A brand has more chance of escaping gimmick territory if realness is integral to their brand and not just an advertising approach, such as The Ordinary with product transparency and Glossier with its community-led mindset.

Q: What are the implications for marketing in other sectors?

A: The trend for realness actually has implications for every sector. The Edelman Trust Barometer revealed that trust in brands in general is at an all-time low, with those seeming the most distant and corporate bearing the brunt of the distrust. As such, brands in many categories are seeking to appear more transparent, authentic and human in order to reconnect with their audience.

Food retail: Successful food brands and retailers are embracing food imperfection, championing ‘ugly’ fruit and veg and adopting messy and ‘real’ food photography.

Banking: Traditionally one of the least trusted sectors, banks are trying to lose their cold corporate image by admitting their faults (ie. Natwest "We are what we do") and casting real people (ie. Nationwide "Voices").

Technology: Bad publicity over questionable ethics have driven the big digital brands such as Facebook, Google and Amazon to search for ways to appear less distant and more human.

The 'new rules' of beauty advertising:

-

Lay off the extreme airbrushing and embrace imperfection

-

Be transparent about your brand benefits, vacuous claims can be damaging

-

Diversity is appreciated, but is fast becoming a hygiene factor

-

To connect emotionally tap into the macro trends of individuality and body positivity

-

Don’t stop at advertising: embrace realness and transparency in your brand values

Bravery Scores

(0-100, with higher scores indicating stronger emotional reactions to ads)

‘Real’ success

50 - Aerie: ‘Real Me’

39 - H+M: ‘She’s a lady’

35 - Dove: ‘#MyBeautyMySay’

34 - Asos Face + Body: ‘Go Play’

‘Fakery’ failure

16 - Olay Total Effects: ‘Is it DNA or is it Olay?’

15 - Rimmel: ‘Live the London Look’

14 - Pantene Foam Conditioner: ‘Strong Is Beautiful’

11 - Maybelline Eyes: ‘Make It Happen’

10 - L’Oreal Paris Elvive: ‘A World Of Care For Your Hair’

09 - L’Oreal Paris Casting Creme Gloss: ‘Fear To Fearless’