Dear Jeremy, I’m a bit stuck. I head marketing for one of the country’s favourite brands but I’ve been doing it for more than five years now. I keep reading marketers don’t stay in the same job very long and I’m worried I should be finding a new role or risk looking stale. On the other hand, I love what I do. Any advice?

Here’s a thought. Don’t you think it possible that marketers don’t stay in the same job very long because they keep reading that marketers don’t stay in the same job very long because they risk looking stale? Even when they love the job they’ve got?

Far be it from me to malign this distinguished profession, but marketing people have been known to be over-conscious of the need to be seen to be ahead of the curve, particularly when the precise nature of that curve hasn’t been identified.

Extremely expensive conferences seem to have been constructed with the sole purpose of making senior marketing people feel unsettled. Everything you painstakingly absorbed about marketing is either obsolete or obsolescent.

Indeed, the end of marketing has been declared on more than one occasion, though its replacement remains unclear. (How unsettling is that?) And, for the best part of ten years now, the inclusion of the word "digital" in any proposal has been enough to ensure it receives uncomprehending attention.

It’s a long time since a senior marketing person said: "I’ve absolutely no idea what you’re talking about. Kindly come back and see me when you’ve learned to speak English."

You’ve been in your job for five years. Thirty years ago, that would have been just about long enough for you to have acquired a real feel for your market and to have earned the respect of your board, your suppliers and your key retail contacts.

It would have given you the confidence to know which elements of your brand should be timelessly preserved, which needed imperceptible refreshment and which needed a total overhaul.

You would have known what your competitors were going to do three months before they did it. And your company would have known that you were now a great deal more valuable to them than when they first hired you five years earlier.

As I’m sure the prime minister would agree, what most marketing companies need in these turbulent times are strong and stable brands. Changing your chief marketing officer every 18 months neatly ensures that they’re never around to live with the consequences of the multimillion pound decisions they made; by then, they’re off to Rentokil or Bristol Zoo. And the new one, fresh from a price-comparison website and Viking Cruises, is certainly going to want to change more or less everything: how else will the marketing world know they’ve arrived?

You’re working for one of the country’s favourite brands and you love what you do. Lucky brand. And lucky you.

Dear Jeremy, Would you agree with me that this recent notion of the "post-truth phenomenon" is a load of nonsense? When was there ever a golden age of truth that we’re failing to live up to today? Shouldn’t brands be more confident and less earnest in their desire for authenticity?

Yes, yes, yes: I would agree with you. Only in agency presentations and sales conferences are consumers passionate about brands.

Only in response to poorly worded research questionnaires do real people voice concern about authenticity and truthfulness.

The very fact that you’re asking the question must mean that there’s some doubt about it, mustn’t it? So I’m certainly not going to sound like an idiot and say that I believe absolutely everything they put in the ads, am I? Who do you take me for?

Mostly, people either don’t much like things or do quite like things. And the things they quite like they tend to buy quite regularly because they quite like them.

What’s pleasing, though, about the whole post-truth, fake-news confection is that good old plodding advertisements, because they don’t pretend to be anything other than advertisements, are seen to be the real thing.

Whereas all those weaselly imposters, perversely attempting to acquire a veneer of authenticity through the practice of duplicity, are increasingly seen to be the charlatans they are.

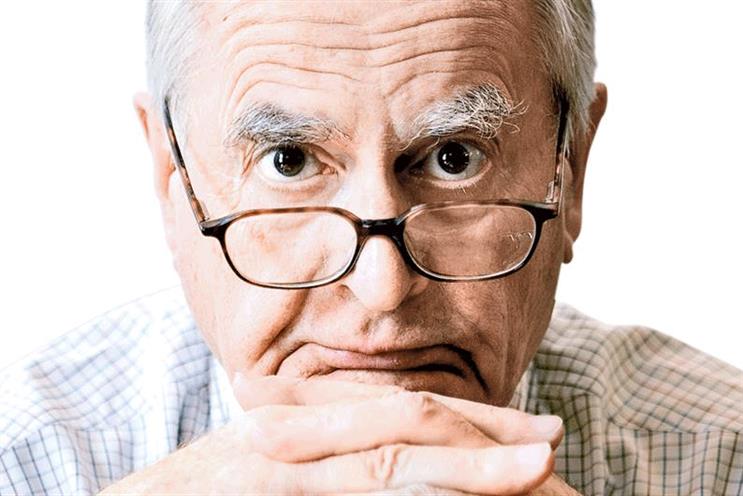

Jeremy Bullmore welcomes questions via campaign@haymarket.com or by tweeting with the hashtag #AskBullmore.