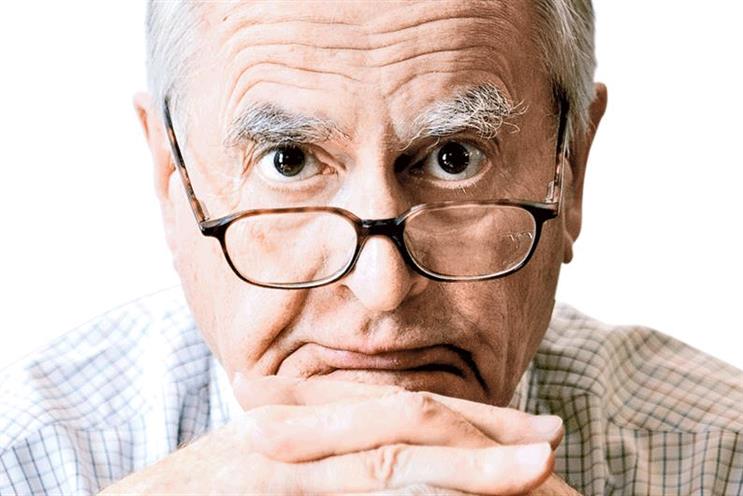

Dear Jeremy, Sweden is introducing a rather dreamy six-hour work day. That’s the additional amount of time I work most weekends! Is it possible that I’d get just as much done in fewer hours if I changed the way I worked? Any tips to do so? Would a six-hour day ever work in adland?

It’s very touching how we cling on to the pretence that we can measure the worth of the work we do by measuring the time we took to do it.

When timesheets were first introduced in advertising agencies, a man with a clipboard asked a copywriter how long it took to write a 30-second commercial. Without missing a beat, the copywriter snapped back: "Six hours and 23 minutes." The clipboard man nodded, the number was noted and was later incorporated into a spreadsheet.

Six months later, the management consultant concerned reported that the agency had three too many copywriters. (They probably did – but it had nothing to do with the time it takes to write a 30-second commercial.)

The late and wonderful Bernard Gutteridge often filled in a whole morning on his timesheet (or, more often, an afternoon) with the entry "Thinking What to Put".

Thinking what to put is an entirely legitimate use of paid-for time for an advertising person, less so, perhaps, for a stenographer.

The eight-hour day is a convenient fiction. Work doesn’t get done in an eight-hour day. Work gets done – and people are paid for an eight-hour day. Mostly it took them three hours or it took them 16 hours. It would be exactly the same if we all worked a six-hour day, a 17-hour day or a two-hour day.

Dear Jeremy, I love reading books but never have enough time to get through everything I want. What should I spend more time on? Books about business, creativity and topics relevant to my job, or novels?

If you’re lucky enough to have an interesting job, the books most likely to be of value to you won’t be about it.

As James Webb Young wrote 70 years ago, "The best books about advertising are not about advertising", and this from a man who’d written one of the very best books about advertising.

There are some good business books but even the better ones would have been even better if they’d been left as the 5,000-word think-piece they started out as.

Book publishers can’t make money out of 5,000-word think-pieces so they cajole their authors (or their authors’ ghosts) into a form of literary botox. They’re like legs of ham injected with litres of water at the abattoir to bulk them up for sale. 5,000 lean, insightful words become 80,000 bloated, repetitive words – often smothering the original, valuable perception altogether.

Sometimes just the title and the subtitle of a 300-page book tell you all that’s valuable about it. You don’t mention biographies. And I do mean biographies rather than autobiographies. Donald Trump’s autobiographical books – The Art of the Deal, How to Get Rich, Think Big – may help you understand how he became president but they won’t help you understand anything else. (His ghost writer claims he wrote most of them but they certainly read as though they were written by Trump.)

If you have to pick just one category of book, I’d go for good, dispassionate biographies of high-profile, complicated people written by rigorous and level-headed professional biographers. You’ll learn little if anything from hagiographies. A good biography of a scientist or a soldier or an engineer or a composer is never of restricted interest only to scientists, soldiers, engineers or composers.

Remarkable lives, well told, invariably have common threads and universal lessons for just about everyone. You’ll recognise their doubts, their prejudices, their insecurities, their introspections. You’ll find comfort on some pages and inspiration on others. And there won’t be anything at all to do with what you do for a living.

Dear Jeremy, This industry is making me fat. How can I politely decline all the lunches and booze?

This industry isn’t making you fat. Sofas are. And greed. And an absence of willpower. You’re not a victim, you’re a creep. Snap out of it.

Jeremy Bullmore welcomes questions via campaign@ haymarket.com or by tweeting @北京赛车pk10mag with the hashtag #AskBullmore.