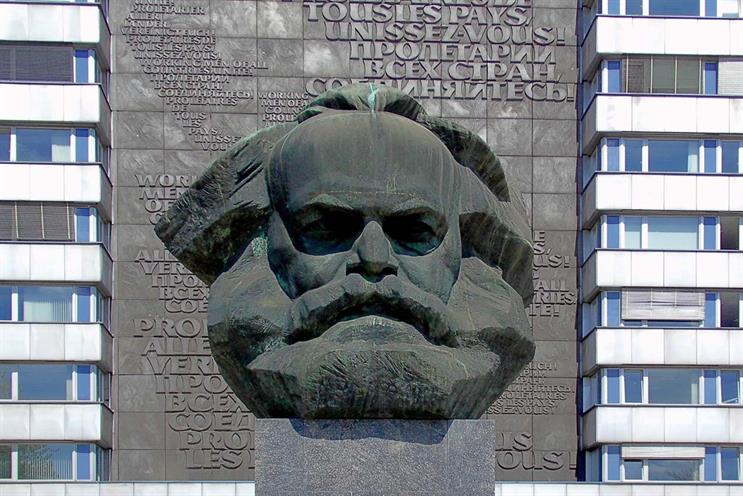

Advertising agencies have always been quietly Marxist organisations. And as they have become weaker, more fragile businesses, their adherence to Marxist economic principles has become ever stronger.

This Marxism isn’t born of any commitment to a fairer distribution of wealth among staff, nor from some seizure of the means of production and exchange among the lumpen proletariat in the design department. Marxism is baked into the agency business model and its fidelity to big Karl’s notion of surplus labour value – the creation of capital by first harvesting and then selling the fruits of other people’s talents.

The agency business model is in fact premised on just one idea: charge more than you pay. Our costs are office space and the brains inside them, so profit is really just your "surplus on people". Unlike the 19th-century cotton mills that inspired and appalled (and funded) Marx, the agency has no particular technique or apparatus. Just talent and time. So, get as much talent and time billed to your client as possible and be sure to always sell up and pay down. This is surplus labour value in its clearest, purest form and it has been an effective model over the years, cultivating a good many ulcer and launching the odd yacht.

But it is becoming a difficult model to sustain. Not for ethical or political reasons – ad people are the delightfully sluttiest of all capitalists. It is unsustainable because it no longer works. Advertising is in a state that economists might call "market failure". Markets are supposed to create the efficient distribution of goods and services, with competitive forces creating value and encouraging innovation. Buyers get what they want at an equitable price and the better suppliers of that need thrive and grow. So far, so Thatcherite. But as literally anyone who has ever bought a train ticket in the UK can tell you, sometimes markets break down and nobody gets what they want. Nobody is happy, nobody’s needs are met and both sides of the exchange feel like they are getting stiffed.

To be technical for a moment, market failures happen when individually rational behaviours lead to poor outcomes for the group. Individual, perfectly rational, self-interest leads to everyone ending up worse off. This is the case for agencies and their clients; our logical market choices are destroying value for everyone.

Large client companies acting according to perfect self-interest, consistently negotiating us down on price and up on scope. The structure of our market, characterised by the oversupply of agencies, and competition across disciplines for the same budget, make this downward fee pressure a matter of economic inevitability. This, and the almost complete absence of barriers for new agency entrants, means that giant companies buy services from smaller ones and often squeeze them pretty bloody hard in the process. Result: the agency gets stiffed.

Agencies respond in the only "rational" way they can – by controlling costs, reducing the numbers of senior staff, getting younger, less well-trained and fewer expensive staff to do more work for less reward. Better still, chuck a bit of freelance at it when the work is there and don’t carry the cost when it isn’t. Even better still, spin this gig economy bullshit in some notion of empowerment and work/life balance. That’s why anyone on moire than £100k in an agency right now better be looking over their shoulder. That’s why the starting salary of a grad in advertising is an ever-shrinking fraction of an equivalent position in law or tech or TV. The ability of an agency to make money on the surplus value of their staff becomes predicated on managing a staff-to-revenue ratio of an ever-shrinking financial pie.

More agencies than talent

This brutal talent economics is really bad news for clients. It is the real reason that the advertising market isn’t working for brands any more. Brand owners are struggling to get what they want from our industry – good ideas and a good experience while getting them.

Historically, the best agencies don’t necessarily have the most stars; they have the most consistently high-performing teams. They don’t just have talent; they have talent density. But advertising’s market failure makes this more and more difficult. The invisible hand of our failing market is driving agency managers into making more and more poor, expedient decisions. The product is getting worse, the talent base thinner, the industry sequentially less able to do the things it was conceived to do. Result: the client gets stiffed.

Individually, no marketing department is trying to grind the quality out of their agencies; individually, no agency manager is trying to asset-strip their talent base. But, decision by decision, negotiation by negotiation and hire by hire, this is what we have all been doing for years. So we are left with a shrinking talent pool spread across too many agencies, with many of our brightest and best jumping ship to places that are less of a grind, less of a struggle. Ask any smart advertising intermediary and they will tell you there are enough brilliant people working in London to populate 20 great agencies. The problem is that they are spread out over 200. It is a problem not just of talent drain but the remaining talent dispersal.

The mood on the ground in agencies seems to be one of exhausted compliance and at the top one of hysterical denial. Let’s give five people who don’t know what they are doing five days to do something really difficult and call it a "sprint". Let’s call the half-thought-through and the half-arsed an expression of new-found "agility". Let’s pretend a bunch a freelancers are in fact all "rapid-prototyping". Let’s call second jobs, conceived to fill what is lacking in an agency career, "side hustles". Above all, let’s "lean in" to the economic gale and pretend we find it bracing.

What is to be done?

Having spent a few years away from the game, I now wonder if I spent most of my time in it as a manager in it entirely missing the point. I worried a lot about "positioning" and capability when all I should really have been thinking about was talent. I fretted about the semantics of agency creds documents when I should have spent more time trying to find, reward and keep the very best people. I didn’t much care for the somewhat blousy discipline of HR as it was practised in agencies and never quite realised it secretly mattered more than anything else.

The only meaningful questions for an agency are how it can pay talented people more than competitor agencies, how it can in turn attract more of the very, very best to work there and hold on to them for as long as possible. How it can have happier clients, do better work and make more money in the process. And, as questions go, it’s a doozy. It’s 3D sudoku performed on rollerblades. Blindfolded.

No company has solved this puzzle, but there are maybe a few clues to what the solution might look like. One is in the consultancy model, where its staff-cost-to-revenue ratio allows younger staff to eat and live a little closer than in zone 5. The consultancies work by charging more per head and per hour, by providing value (or perceived value) to clients by delivering more structural interventions in a business than this year’s ads or content calendar.

Agencies still frame their offering in a disposable, output-driven way. In a world of zero-based budgeting, there is no longer the cosy assumption of this year’s budget to be spent on this year’s campaign. Those days are gone, probably forever. But we deliver outcomes that matter via executions in which we are excellent. Agencies’ real outputs are launches, relaunches, growth, loyalty, conversion. Perhaps we need to sell these outputs as products and stop assuming that any business automatically wants "ads" or "digital" or "content" any more. The agency of the future will "productise" these outcomes and sell a menu of valuable business tasks, configuring their outputs to deliver these bigger, less frequent communication interventions. We will replace the decrepit model of retained services with an ambition for highly valued repeat business.

Delivering greater value by answering bigger business challenges is a commercial strategy for the top line that may make some meaningful marginal differences to agency economics, but on their own they are unlikely to do enough. Doing more valuable work is part of the equation, but it will be swimming against the tide of dramatic oversupply and procured pricing. To be able to pay more, we must also spend radically less.

Agencies need to focus on becoming dramatically leaner, with small, tight teams of people doing genuinely valuable things and nobody seemingly just along for the ride.

This sounds harsh, but agencies have to start focusing solely on value-added activities and start eliminating everything else. It is a change that will demand a transformation in culture and radically more cost-effective day-to-day operations. Putting people and talent first will be a bloody business, delivered by culture and, perhaps surprisingly, by tech.

Culturally, we will have to find a way to marry high rewards with high expectations and a much more rigorous and competitive way to identify high (and low) performance. A great agency needs to be a hard place to get into and perpetually demanding to stick with, but one that's worth it. Financially, professionally and emotionally.

A changed culture can’t take hold if the way an agency operates remains the same. If the goal is to create an agency that has as few staff as possible but pays them more than anyone else for delivering things that clients are willing to pay more for, then technology needs to come to the aid of talent. Technology needs to set agency people free from the menial and the mechanical, the monotonous and unimaginative. And agencies are still full of this kind of work.

Artificial intelligence-driven automation is beginning to make real headway into a variety of white-collar professions. Perhaps the time has come to go further and see what can be done in our own world. If multi-variate digital and social creative execution is better handled by a bot called Malcolm, it should be done by a bot called Malcolm. AI could allow us to concentrate our resources on the human imagination, on people who can do the extraordinary things that technology can’t. Messaging automation won’t write the next "Just do it", but it will populate the nudging army of conversion ants that are necessary part of modern communications. We need to be sure we are paid handsomely to do both.

If the agency business is to survive and thrive, we will need to find tech-enabled ways to put human talent and creativity first. It is time for a new vision for agencies: to find, inspire, reward, train and unfetter the most imaginative people in business, to build a company and way of working that lets them do nothing but express their talent for the sake of good clients who value and reward the quality of that work. It won’t be easy, but the agency that wins will find a way to get the best people in one place and give them the tools they need to build an industry anew.

David Bain is founding partner of BMB