It’s not hard to see where Carlsberg was coming from when it decided to completely overhaul its main UK beer. It had almost nothing going for it: fighting for sales in a shrinking corner of the market, a brand that consumers understood poorly, with many believing it originated in Ireland rather than Denmark.

The product, a low-alcohol lager created for the philistine Brits that had little in common with authentic European pilsners, was considered pretty poor by many – but its reputation was perhaps even worse. So it made sense to create a brand new beer to sell under the new, classier name of Carlsberg Danish Pilsner.

Whether the new brew is a drastic difference is certain to divide commentators – Twitter account Craft Beer Channel took great pleasure in pointing out that, even after the revamp, 41% of beer drinkers still preferred Carling, with the implication being that it is hard to think of anything worse.

Snobbery exists in every consumer category, but seems to be particularly overt and acceptable when it comes to alcohol. The realty is that no-one’s preference is "correct"; just because the folks at Craft Beer Channel know a lot about hops doesn’t mean their favourite drink – which ±±ľ©Čüłµpk10 assumes is Voodoo Jazz Hat – is actually any better than Carling, Carlsberg (old or new) or anything else. Some people like a mildly flavoured drink and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that.

But what Carlsberg has done is moved the brand in the same direction as consumer preferences. The new beer keeps the low alcohol content that appeals to people who want to moderate their drinking, but has far more flavour and body than before, and is likely to be considered an improvement by most people who try it.

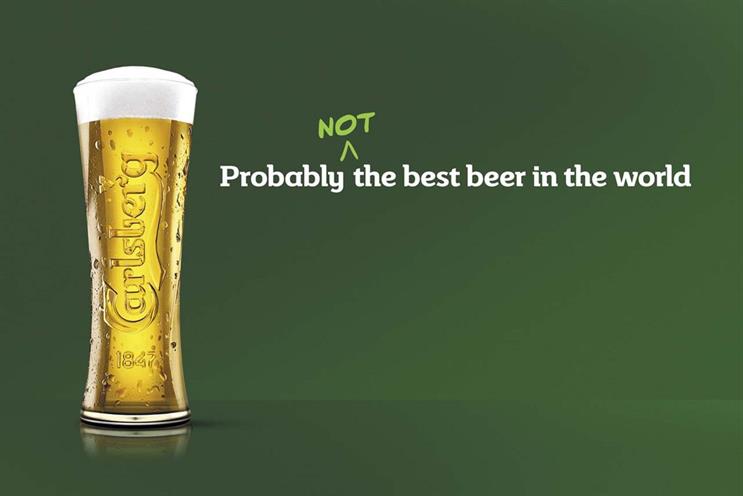

A bold move like this, though, posed a problem for a brand that had spent years claiming to be probably the best, even if the claim was made with tongue firmly in cheek and was not taken literally by many.

Carlsberg's solution was a kind of marketing self-flagellation (with a campaign by Fold7), in which it drew as much attention as possible to its past wrongs before anyone else could, while promising it had learned from its mistakes and was now a changed beer. But will this ploy get the message across?

Yelena Gaufman

Yelena Gaufman

Strategy partner, Fold7

It’s rare that a recipe change isn’t a tweak shrouded in marketing fluff. This was that rare occasion. We had a completely new brew on our hands that we needed to get people to try. But we were fighting general consumer scepticism and disinterest in lager, as well as more specific perception issues with a brand that hadn’t lived up to its promise in a long time. Being bold and honest was really the only way for us. The engagement we’ve seen so far has been incredible. Brand rejecters are trying the new brew and coming back to Twitter to give it a thumbs up.

Cat Wiles

Cat Wiles

Head of planning, VCCP

I love the strategy – it’s bold, ambitious and playful. Both Marmite and Skoda prove that a self-deprecating strategy can have legs, if executed correctly. However, for me, this is where Carlsberg falls short. The work makes a functional statement, but fails to make an emotional connection beyond the apology. It is lacking any of the wit, charm or originality that we’re used to from this iconic brand. The strategy could pay off, but Carlsberg will need to quickly move from creating a debate to finding something more enduring that propels the brand forward. Hopefully, that’s just round the corner.

Sophie Lewis

Sophie Lewis

Chief strategy officer, VMLY&R

I love the Carlsberg campaign. I love a bit of humility and the acknowledgement of a fuck-up. I’d say it owes a little debt to KFC and their fries, but getting your fries a bit crispier is arguably easier than reworking your whole beer-brewing recipe.

And, the truth is, who isn’t going to try it? I will, and I suspect I’ll love it. Not because I think it’s going to taste significantly different, but because I know it’s changed and I appreciate the honesty/candour/desire to do something interesting in a troubled category. Well done, client. Well done, agency. Growth beckons. Probably.

Chris Gallery

Chris Gallery

Strategy partner, Mother

When we sponsored negative tweets for the launch of KFC fries, it created a great platform to launch a new product… but KFC never promised that they had the world’s best fries – and they’re always on the side of the main event.

You’ve got to applaud any launch/relaunch that actually cuts through to culture, so well done on that. Time will tell if it was worth it to get editorial and Twitter abuzz for a day.

I just can’t imagine ever creating a campaign for 11 different secret herbs and spices, saying: "Sorry we’ve been wrong since 1952. Oops."

Rania Robinson

Rania Robinson

Chief executive, Quiet Storm

The mean tweets idea isn’t original – other versions include something similar we did for The Mirror a few years back. But, in many ways, it feels more meaningful. To publicly recognise falling short of the claim it became famous for at a time when advertising was taken at face value feels appropriate and necessary. Today, brands get called out for not living up to their promises. Having the self-awareness and genuine commitment to delivering against them feels smart, with potential to trigger the reappraisal it so desperately needs. Assuming, of course, the product lives up to the new promise.

Craig Mawdsley

Craig Mawdsley

Chief strategy officer, Abbott Mead Vickers BBDO

It certainly looks like a bold move, doesn’t it? You must admire the honesty and the willingness to grasp the nettle by changing the product, not just the advertising. And in a category that tends to trumpet heritage or novelty, this seeks to forge a middle path – a brand you know, but almost totally reinvented.

That’s where I get concerned about it. It runs the risk of being too much like Carlsberg and not quite enough like Carlsberg at the same time. Is it going to work?

[Please insert your preferred old or new Carlsberg endline-related reference in here.]

Ant Firth-Clark

Ant Firth-Clark

Senior cultural strategist, Canvas8

Yes. It will go down as a funny, well-executed beer campaign. The self-deprecating aspect certainly has publicity-grabbing novelty, which will likely drive an initial spike in consumption of the pilsner, especially amongst younger consumers who’ll appreciate the brand's humorous transparency.

However, the attempt to make the brand more "premium" feels like a hopeful elevation tactic. The strategy will be effective in getting people to revisit the beer brand but, as a growing number of people become more discerning with their beer choices, the desired longer-term shift will ultimately come down to the execution of the beer itself.

.jpg)

.jpeg)