Netflix has backtracked on pursuing trials to gamify its kids content by offering viewers digital badges as rewards and incentives to stay watching. The initial backlash against this had been that it is a nakedly self-interested move to keep children watching, turning our kids into binge-watchers. This is fair enough: it is.

But of course, this is nothing new and it’s not just Netflix that does this. The gamification of everything, everywhere is a well-engrained system of nudging people’s behaviour in search of perpetual "engagement".

Look at Nike Running Club challenges, Audible’s shields and badges, or literally anything on Facebook. Goodhart’s Law states that ‘when the measure becomes the target, it ceases to be a good measure’. So, there is a question as to why Netflix – with record subscribers, revenues and huge pipelines for original new content – needs to make such short-term, tactical moves.

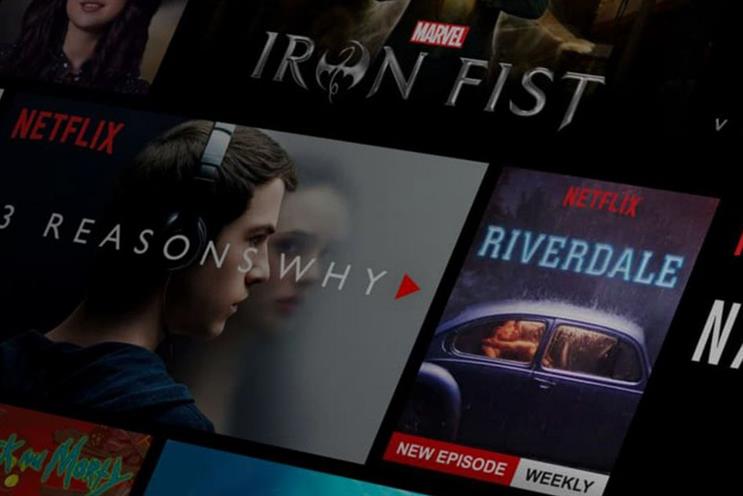

Currently, Netflix doesn’t rely on advertising to fund its programmes. But its model does have a parallel with advertising. Just as it is far more expensive to acquire new customers through advertising than it is to retain existing ones, Netflix brings people in with its big-hitting classics and shiny original content, but keeps people in with cheap-to-acquire reruns of Buffy, Highway Thru Hell and persuasive design to keep you streaming.

As Stephen Witt writes in the Financial Times, this is successful because ‘people love garbage’. Netflix’s reputation is greater than the quality of its content or user experience, where people spend an inordinate amount of time searching and choosing, or watching ‘junk’ (Faris Yakob’s on balanced media diets is great on this).

With kids’ shows though, something different is going on. Of course, there are always concerns about the amount of time kids spend on screens, or that toddlers can swipe before they can hold a set square. But there’s also a problem with the quality of shows for kids.

With in advertising aimed at children, the value of such programmes has dropped, so there is less good stuff being made by broadcasters for children. Unless it is enshrined in their remit, like the BBC for example, the commercial incentive for broadcasters simply isn’t there. And when you look at the current state of YouTube, with some users creating disturbing ‘kids’ videos, as James Bridle recently , there’s not a great choice for parents or children.

The supposed agnosticism of media technology platforms has been a huge strength in fuelling user growth. But today, that very agnosticism gives rise to accusations that the platforms themselves don’t care about the impact of the content they serve people.

Facebook recently for suggesting offensive and upsetting searches about children to users. YouTube’s announcement that it will supplement conspiracy videos on its site with Wikipedia entries to tell the truth is odd: the largest video platform in the world will rely on a volunteer-run encyclopaedia to give its content credibility. And this is changing how people see these companies. As Tom Cheshire recently , ‘before every select committee hearing on extremism or fake news, MPs will go and find objectionable content on a platform, then use it to castigate the tech firms on a very public stage.’

So, there’s a huge opportunity for a trusted creator and distributor of programmes for children, one known for making things that are entertaining and good for children, rather than chasing dopamine hits in toddlers.

In the way Channel 4 has a strong reputation of being for young people, with a clear sense of direction and principles to move beyond engagement-only metrics, Netflix could become the brand of choice for millions of harried parents everywhere. What if it didn’t just invest in original content for kids, but worked with cultural and educational institutions to develop new entertaining curricula that was both for screens and the home, classroom and the car seat?

It’s not the current remit, but would help move the brand beyond the agnosticism of ‘engagement’ and into something more meaningful and useful for millions. More than a platform, more than a bottomless pit of programmes, but a trusted and creative service that parents and children alike can access and enjoy without fear of compromising children’s development.

Dan Gavshon-Brady is lead strategist at Wolff Olins