The long march of social purpose through adland’s institutions continues apace. And this time, the IPA looks like it’s fallen into step.

Last October, its “guru of effectiveness”, Peter Field, released his , which appeared to cherry-pick examples in order to make the case for brand purpose.

Now, the IPA is changing its famously rigorous rules in a way that is likely to make it easier for social purpose campaigns to enter its Effectiveness Awards, and, by inference, to win one.

As last month’s report recommends, the primary criteria should be:

"1. Value Contribution: How impressive is the financial, social and/or environmental contribution of the activity to the business (whichever is applicable given objectives of case).

2. Strength of Proof: How convincingly and credibly does the paper establish the link between the activity and value contribution?”

In other words, from now on – despite – entrants will no longer have to reference ROI or, indeed, prove that the work actually sold anything.

This amendment is unnecessary. The report cites examples of excellent social purpose entries that have won under existing criteria. And projects that are not-for-profit have always been accepted and awarded. This decoupling of financial outcomes from effectiveness is bad for the industry, and maybe even worse for the IPA Effectiveness Awards brand.

IPA Effectiveness Awards’ Purpose

When the IPA launched its awards in 1980, it was ridiculed by many who thought it impossible to measure the impact of one element in the whole marketing mix.

But the IPA went ahead with this as its “purpose”. Yes, it used that term, but in this case it was very much a commercial purpose: “To demonstrate that advertising can be proven to work against measurable criteria, for example, sales measures and show that it is both a serious commercial investment and a contribution to profit, not just a cost.”

It then set itself two challenges: “First, to prove that advertising could add value and demonstrably contribute to profit and, second, in doing so, to develop and spread best practice.”

If ever there was a time to encourage that “best practice”, it is now.

Remember the “Crisis of creative effectiveness”

Little more than two years ago, the IPA declared “a crisis of creative effectiveness” saying that “Creatively effective campaigns are now less effective than they have been in the entire 24-year run of data and are now no more effective than non-award winning campaigns.”

Where once a creatively awarded campaign would be about 12 times as efficient as non-awarded ones, the multiplier is now in “catastrophic decline”.

Needless to say, those campaigns that dominate at Cannes and D&AD give scant proof the work has worked. Indeed, as chairman Tim Lindsay once said of the latter, some award-winning, purpose-driven work is “undoubtedly a scam”.

To repair the industry’s reputation and reintroduce rigour, the IPA launched its “Effectiveness Accreditation” in April last year. It was to be the commercial equivalent of B Corp certification. Alas, president Julian Douglas’ effort “to build an effectiveness culture within agencies day-to-day” has thus far attracted just six of the top 100 creative agencies in the UK, according to Nielsen. .

What C-Level clients want

It suggests our biggest shops have little appetite – or maybe even aptitude – for effectiveness. Which is a key reason C-Suite clients don’t take them seriously.

You’d expect the IPA to know this. Marc Nohr, chair of its commercial leadership group, certainly does: “Ask C-suite execs what sort of conversations take place in a boardroom, and you’ll hear the same thing: profit and loss, growth, productivity, commercial performance. They just want to see marketing investment increase market share, minimise defection or drive numbers in some meaningful way.”

With rising inflation and the cost of living crisis curtailing consumption, this focus on the bottom line will only intensify.

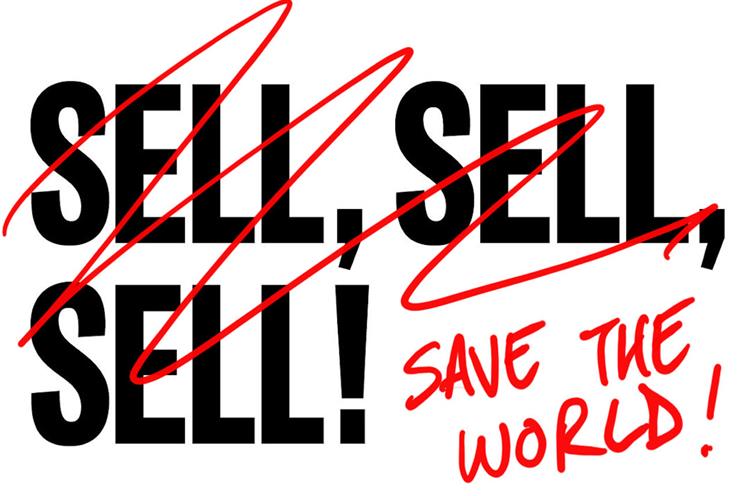

But when it comes to entering the revamped Effectiveness Awards, agencies will be happier talking about the kind of work they enjoy doing – and which they like giving the balloons to ().

Precisely the kind of work, in fact, that pushes clients ever closer to the digital and direct sales activation shops that promise “more for less” and instant ROI.

In such dire circumstances, you’d expect the IPA to double down on its commercial purpose. Yet, remarkably, it is watering down its emphasis on financial accountability.

It’s called a “sales funnel” for a reason

Les Binet and Peter Field, have often used the IPA to argue for the sales funnel – and the budgetary split that makes it a cornerstone of marketing strategy.

But it is called the “sales funnel” for a reason. Its objective is to build brands that people want to buy. This can be achieved by improving differentiation, trust, distribution, media coverage, employee satisfaction, mental availability etc. But the proof of the entire process – and the justification for the client’s marketing spend and their agency's fees – is that people did actually buy something.

If the IPA removes this from the criteria used for judging effectiveness, then its awards will lose their purpose. And a great brand, which all of advertising could be proud of, will become increasingly irrelevant. And so, too, will the industry that no longer has an awards show that keeps its balloons anchored to the ground.

Steve Harrison is a creative director and author