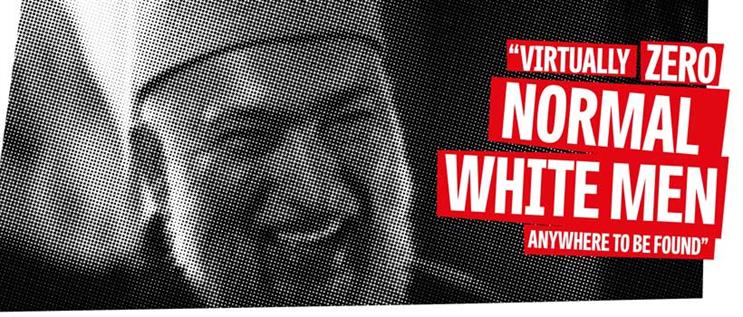

Sentiments like the one listed above are a common – if not entirely representative – feature in the comments section of blogs, YouTube videos and op-eds on the issue of diversity.

Such views, which decry "too much diversity", seem to be proof of a toxicity and fear in some quarters, now that the visibility of people of colour, previously omitted from media and advertising campaigns, has improved.

Of course, the issue of "political-correctness-gone-mad" cries from the loony fringes of the internet is nothing new whenever a brand or a channel gets a recognisably more diverse refresh. But figures tell us that, in the UK, only 7% of lead roles in advertising campaigns are played by someone from a BAME group. This belies the data from the most recent UK Census, carried out in 2011, which revealed that people from a BAME background account for 13% of the UK population.

In 2018, Lloyds Banking Group commissioned a study on ethnicity in ads. Its report, "Ethnicity in Advertising: Reflecting Modern Britain in 2018", is considered among the most insightful and comprehensive on this topic. The study found that although BAME groups are better represented in advertising than at any other time in history, they often appear in supporting, rather than leading, roles, and that three out of five ads feature an all-white or majority-white cast.

Anna Arnell, creative partner at And Rising, has previously expressed her disappointment at those who leave racist slurs in the comments section when her ads are posted to YouTube, and has an air of resignation when discussing race rows on Twitter. "I think some people feel like seeing ethnic people in ads is a threat to their white British culture," Arnell says. "They seem to think that anyone who’s not like them doesn’t belong in their world. Often, when we see work being done to redress a balance, it can feel scary to some people. But really there is no need for people to feel scared of the changes happening around them."

She adds: "We’ve had years and years of stories being told by the same voices. We’ve now got to embrace different stories. That’s how we grow as humans, by seeing different people’s stories."

"We’ve had years of stories being told by the same voices. We’ve now got to embrace different stories"

— Anna Arnell, And Rising

More advertising has started to represent people of various cultural backgrounds and with different stories. The BBC also boldly attempted to do the same with its recent adaptation of the Noughts & Crosses series of books by Malorie Blackman. The drama portrayed an alternative history in which African people colonised and enslaved Europe’s population. It immediately received a backlash from some viewers who were affronted by seeing white people on the receiving end of racially motivated discrimination.

Despite doing an important job of highlighting the ultimately arbitrary nature of discrimination in society, the team behind the production faced a raft of poor reviews posted on the movie information and ratings website IMDb, which could jeopardise plans for future series of the show.

Koby Adom, who co-directed the series, tweeted in March: "Please do me a favour. If you enjoyed #noughtsandcrosses on BBC 1/iPlayer, please go on IMDb and give us a star rating. The retracted (sic) brigade came out in full force, so star rating is low. Let’s balance it all out. Retweet this also/spread the word."

Not surprisingly, work that challenges preconceived – and often outdated – societal mores can draw extreme criticism from politically motivated audiences for whom privilege is a concept that is not shared by all.

Andy Nairn, founding partner at creative agency Lucky Generals, admits that one of the big challenges his agency grapples with is unconscious bias. "Everyone at our agency goes on unconscious-bias training," he says.

"It’s a big undertaking and we refresh it every year. It’s now part of our culture. It helps uncover the things that we stereotype in our minds, the things that we bring to our creative work, if they go unchallenged. In production terms, we are also putting in the work by having consultants on set who are there to point out any signifiers – props or costumes – that don’t seem consistent enough with real-life characters."

Morally, the ad industry is right to be increasing the breadth of characters cast in campaigns, but it’s also an imperative, commercially speaking. And while the range of ethnicity in ads has improved, it needs to go further if it is to reflect the diversity of the British population as a whole and overturn the continuing negative stereotyping and frequent lack of nuance in cultural references.

The Lloyds "Ethnicity in Advertising" paper reported that 42% of black respondents think advertisers don’t do enough to recognise their culture, while 29% feel that they are on the receiving end of negative stereotyping.

"The number of kids under the age of 10 who are mixed-race and the number of under-fives who are Muslim now make up a large proportion of our country’s population. So we need more representation, not less"

— Karen Blackett, WPP

Gen Kobayashi, chief strategy officer at Engine, is concerned about the large percentages of black people and Asian people who feel that they continue to be inaccurately portrayed in advertising. "Until this issue is sorted, no-one can have any complaints about ‘too much diversity in advertising’. These figures mean that, as advertising professionals, we’ve not been able to connect with a huge number of people. I think that this might be because people can see through the inauthenticity of some ads. I mean, you’ll always have voices of discontent, but we need to keep making work that’s more representative regardless."

Karen Blackett, WPP UK’s country manager, has been working hard to correct the many imbalances within the ad industry. She says: "The core issue here is that our population is changing. Take a look at the demographics: the number of kids under the age of 10 who are mixed-race and the number of under-fives who are Muslim now make up a large proportion of our country’s population. So we need more representation, not less. We should definitely not pander to the people who can’t cope with how Britain is changing."

Official Census data shows that the purchasing power of BAME communities increased from £30bn in 2001 to £300bn in 2011. "This new generation has gained massive amounts of purchasing power. In the current climate, we’d be mad not to serve this cohort," Blackett adds.

She continues: "Although we’ve been trying to get it right, we’re still not getting our stories told authentically. I think these kinds of conversations wouldn’t have been happening five years ago, but the problem at the moment is that we’re trying to do representation, rather than true diversity."

In short, this is not a tick-box exercise. Nonetheless, Blackett’s final remarks are unwaveringly positive: "I’m confident that we’ve entered an era of sea change."

The Advertising Standards Authority and Committee of Advertising Practice’s code states: "Particular care must be taken to avoid causing offence on the grounds of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability or age." Additionally, in June 2019, further guidelines were implemented that cover the offensive use of stereotypes.

A common issue for BAME groups in seeing representations of themselves in ads, is that there is often very little recognition of cultural difference. Diversity does not always mean complete immersion and assimilation into a homogenous Western culture. There is currently little attention being paid to specific cultural heritages and the contribution this has made to modern Britain.

That’s not to say it’s not possible to respect both heritages. Amazon’s 2016 Christmas ad, created by Joint London, depicted a friendship between an imam and a priest. Both men had problems with aching knees and, after meeting, they separately sent each other identical gifts of knee pads. The spot was widely praised for its portrayal of the community overcoming, and embracing, different cultural traditions with a common human theme.

Ultimately, the diversification of the ad industry is a complex issue. It will take some time for the sector to handle the stories and lived experiences of the multitude of people of colour who live in Britain, with accuracy and authenticity. But in the here and now, the industry needs to be more aware of its biases and strive to become more inclusive. The recent Black Lives Matter protests in the UK are vivid proof.

Brands getting it right

According to the Lloyds Banking Group "Ethnicity in Advertising" report, BAME representation in advertising more than doubled in the three years to 2018, with 25% of the people in ads during 2018 from BAME groups, compared with 12% in 2015.

This increase in representation may have been due in part to the #ChristmasSoWhite campaign of 2016, for which advertising consultant Nadya Powell created a pioneering stock image bank of black and ethnic minority families enjoying the festive period.

The BBC’s 2017 Christmas ad "The supporting act", made by BBC Creative, showed a schoolgirl preparing for a dance performance, while her father is repeatedly distracted by work. At the performance, the girl is struck by stage fright until her father joins her in the dance. While the ethnicities of the characters portrayed were ambiguous, it was not the main theme of the ad; rather it was the realistic portrayal of single-parent family life that resonated with audiences and won the ad widespread acclaim.

Tesco’s ongoing "Food love stories" campaign, created by Bartle Bogle Hegarty, was launched in 2018. It features a range of BAME groups telling the stories behind dozens of different meals, including world food favourites jerk chicken and curry.

Race complaints submitted to the ASA and CAP

In the two years to the end of March 2020, the Advertising Standards Authority received 992 complaints about 562 ads on the grounds of race.

An ASA spokesperson said: "A sizeable number of complaints where race is mentioned concern people objecting that there aren’t enough white people in ads, or there is an overrepresentation of ethnic minorities in ads. We also get complaints at a regional level, for example as complaints which assert that an ad unfairly stereotypes Scousers and is, therefore, racist."

Within this two-year period, just one formal ruling was upheld, the details of which are below.

Ad description

A press ad for Vic Smith Beds, which ran in the Enfield and Haringey Independent newspaper on 12 February 2020, featured a cartoon of a mattress, with a Union Flag on its front and wearing a surgical mask. The copy read: "British build [sic] beds proudly made in the UK. No nasty imports."

Issue

Two complainants challenged whether the ad was likely to cause serious and widespread offence by linking concern about the ongoing coronavirus health emergency to nationality and/or race.

Response

Vic Smith Beds said it would ensure the ad was not repeated. It said it had not been its intention to cause offence and that its customer base was a multi-ethnic mix, so it would not have made sense to offend its customers.