Tesco is a case in point. It was the first major retailer to have its products linked to the contamination and has been closely tied to the story ever since.

In most of that time its main conduit to talk to its customers has been a series of press ads, which it has used to reassure them and apologise.

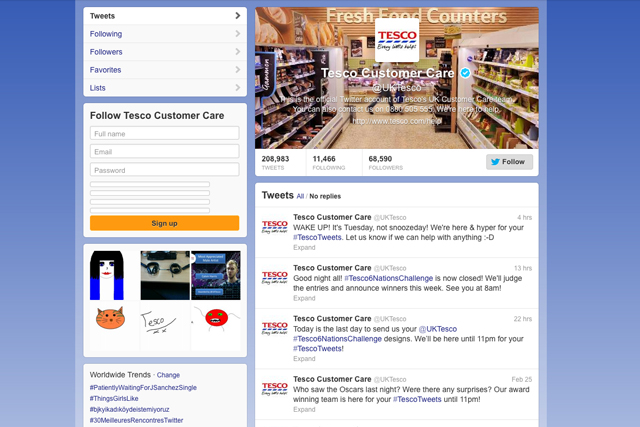

What it has not done is say a word about any of this on Twitter. Its feed contains no mention of horsemeat in the past two months - not even of the apology ad or 'farm and factory' website it announced as part of a drive to make its supply chain transparent.

The only tweet that could have been construed as a reference to the horsemeat situation was what appeared to be a joke, posted early on in the scandal: 'It's sleepy time so we're off to hit the hay! See you at 8am for more.'

Roundly criticised

Some roundly criticised Tesco for this, arguing it was too soon to make jokes - all a bit po-faced, I feel. Many others, however, gave a more positive reaction and took it for what it was: a very British response to the situation - a small joke. It was one that was shared more than 3000 times - after what by then had been days of serious news about how many burgers contained traces of horsemeat.

Tesco later apologised, saying it never intended to make light of events, and the tweet had been 'scheduled before we knew of the current situation'. Make of that explanation what you will.

Since then it has ignored the horsemeat scandal on Twitter, despite the story continuing to be one of the most-talked-about on social channels.

At the International Business Festival event in London last week, Sir Terry Leahy, the former Tesco chief executive, refused to be drawn on why had been so quiet.

All this provides a good example of how companies are failing to manage their Twitter feeds and use them to best effect during a crisis. It is a problem that is damaging trust in brands, according to most of the PR chiefs who spoke to PRWeek recently.

Batten down the hatches

One can understand why, to an extent. There is a tendency when a brand is under fire to batten down the hatches, as lurking just below the surface is a palpable fear that saying something will risk giving the issue oxygen.

The other consideration is how some of the Twitter feeds of companies like Tesco are operated. Its main @UKTesco account acts as a customer-service channel dealing with issues relating to food deliveries and product availability, rather than more weighty matters.

That, in part, explains the hay joke and crisis-management response that followed. It probably wasn't something sanctioned by the PR and marketing team, which clearly ruled subsequently that under no circumstances were those tweeting via @UKTesco to mention horsemeat again. They haven't.

The result has been radio silence and nothing from the PR and marketing team (its media account, , has also remained mute).

That's a mistake and a missed opportunity - and that's the core of the issue. The people who could be crafting messages to reassure customers and build trust are not doing so. They are not engaging.

Twitter accounts at major British companies like Tesco should be many things: flexible, multifaceted, and reflecting all the issues their customers are talking about - otherwise, they are failing.

Gordon MacMillan is social-media editor at the Brand Republic Group and editor of The Wall blog.