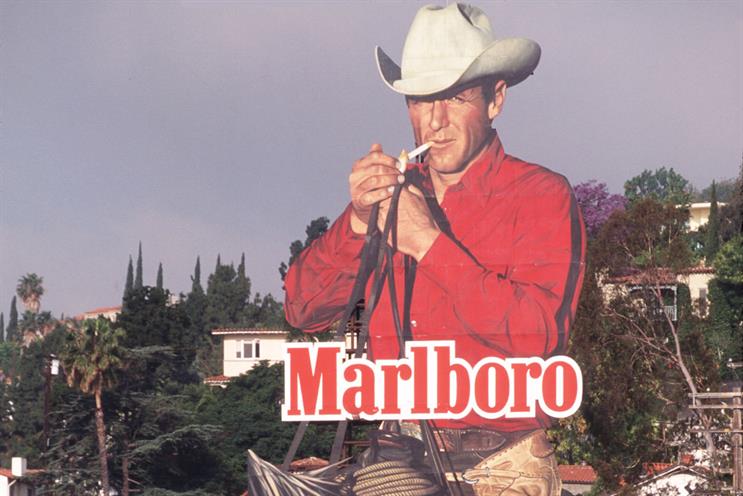

When Marlboro "cowboy" emerged as the winning campaign at the Advertising Association’s Last One Standing event, many in the audience must have felt this was not quite the product category the event’s sponsors had hoped to prevail. It is an awkward but undeniable fact that, among the many commercial successes in history that are almost entirely attributable to great advertising, two of the greatest are Marlboro and De Beers: fags and diamonds. No wonder we all love talking about that Volkswagen campaign so much.

Nevertheless, the Kenco brand manager, Emad Nadim, presented his case convincingly – so much so that I was prompted to research the origins of the Marlboro campaign a little more.

I already knew plenty about the De Beers campaign and its success in creating perceived value for diamonds, until then a relatively minor gemstone. Lines such as "How else can a month’s salary last a lifetime?" are, in my opinion, as great as "lemon" and are a rebuttal to the popular notion that the pre-Bernbach advertising industry was inhabited exclusively by dimwitted WASP posh boys.

But I knew much less about Marlboro. I was vaguely aware that the brand had been launched as a cigarette for women. What I didn’t know at the time was that all filter-tipped cigarettes were seen as feminine. Not only had Marlboro been launched with the slogan "Mild as May", but its filter was once surrounded with a red protective band: "Beauty Tips/to Keep the Paper from your Lips."

Marlboro initially sought to reposition the brand as one for men, targeted at that "small niche" of males who were concerned about the risk to health from smoking. To this end, it sought to reduce the stigma attached to filter cigarettes among men.

In truth, it was probably a bit lucky. There were initial plans to feature a range of Marlboro figures in the advertising, moving from cowboys on to other rugged individualists – truck drivers, lumberjacks, oilmen and so forth. The cowboy was so successful to begin with that it made a decision to stick with him exclusively. Good call.

In truth, it was probably a bit lucky. There were initial plans to feature a range of Marlboro figures in the advertising, moving from cowboys on to other rugged individualists – truck drivers, lumberjacks, oilmen and so forth. The cowboy was so successful to begin with that it made a decision to stick with him exclusively. Good call.

But it was also lucky in its agency – which persisted in promoting the campaign when Philip Morris was doubtful. It was lucky, too, in its other advisors.

One of these was Louis B Cheskin. I had forgotten about Cheskin since reading The Hidden Persuaders about ten years ago. Cheskin was a Ukrainian immigrant to the US who, alongside Edward Bernays and Ernest Dichter, was one of a group of European psychologists selling their skills in uncovering unconscious influences in human behaviour.

Cheskin, whose original specialism was the psychological use of colour, proposed that the Marlboro packaging should suggest a medal worn around the neck as an unconscious cue of masculinity. He supported the cowboy campaign and later had a hand in Marlboro’s introduction of the hard, flip-top cigarette packet – an invention that, by creating a ritual around opening a pack, contributed almost as much to the addictive nature of cigarettes as nicotine.

What is strange about the generation that included Bernays, Dichter and Cheskin is that they created an adverse reaction against the unconscious school in marketing. Not because they were useless, but because they were so effective. So paranoid did the discipline become over attacks such as The Hidden Persuaders that, for 50 years or so, most marketing operated under the ridiculous pretence that people make purely conscious rational decisions and can accurately explain the reasoning behind their actions.

I am delighted that Marlboro won. Understanding its genius can help in many other current challenges

So I am delighted that Marlboro won. I suppose you could claim that, by encouraging men to switch to filter cigarettes, it may have had some health benefits – but this is probably stretching the truth. But understanding its genius can help in many other current challenges – solving problems of the environment, health and social behaviour.

In any case, we desperately need better psychological models in marketing. The other entrants to Last One Standing embraced fields as diverse as digital marketing for small businesses, the TAP campaign for Unicef, product placement and advertiser-funded content. This breadth made it clear that advertising now encompasses such a broad range of possible activities and interventions that the old measures and metrics, and simplistic assumptions about how human behaviour works, are no longer fit for the job.

So one way to prepare for the future is by studying the 50s.

Rory Sutherland is the executive creative director and vice-chairman of OgilvyOne London, and the vice-chairman of Ogilvy & Mather UK