I read something interesting by the new Booker Prize winner the other day. Not his novel (I'm sure Lincoln in the Bardo is great but I’m afraid a 288-page historical fantasy, based on a series of graveyard monologues, is going to have to wait until the Christmas hols). No, I’m talking about a somewhat shorter piece in The Guardian.

In it, George Saunders argues that embracing the unexpected is a vital part of the creative process. While preparation is important and the first draft a necessary evil, the real magic comes in the subsequent editing and execution. At some point, there has to be a leap into the unknown, a departure from the original brief because: "Simply knowing ones intention and then executing it does not make good art."

He suspects all writers work this way, memorably quoting Gertrude Stein on the point: "If you start out to write a poem about two dogs fucking and you write a poem about two dogs fucking - then you wrote a poem about two dogs fucking." And while I hardly think our own scribblings are in the same literary league (or should even have the same artistic pretensions), I feel the same basic point applies in our world. Briefs should function as springboards rather than as railroad tracks: providing inspiration rather than leading inexorably to a predetermined destination.

If you spend months developing something that turns out exactly how you first imagined it, you should probably be worried rather than comforted

This holds true at every stage of the process. A great client brief should leave room for a good planner to build on the strategy, not just present it fully-formed on the plate. A great agency brief should allow space for creative people to make lateral leaps, not just provide a template for them to colour in. A great research brief should focus on the objectives and hypothesis, not dictate the details of the methodology. A great production brief should ask for fresh eyes rather than insist the director, designer or photographer sticks slavishly to the script. And, perhaps most of all, a great process should allow for some magic to happen "on the day", "in the market" or "in culture", that nobody could ever have imagined (let alone at the start of the process).

Of course, if there are too many sideways moves at too many points in the journey, then the thinking can be blown off course. But even here, it’s legitimate to ask whether this is necessarily a bad thing: a strong team should have the humility to learn as they go, and embrace new solutions that emerge along the way, if they lead to a better – albeit unexpected – place. In fact, if you spend months developing something that turns out exactly how you first imagined it, you should probably be worried rather than comforted - because it will likely be on brief but unremarkable.

Do a Dunlop

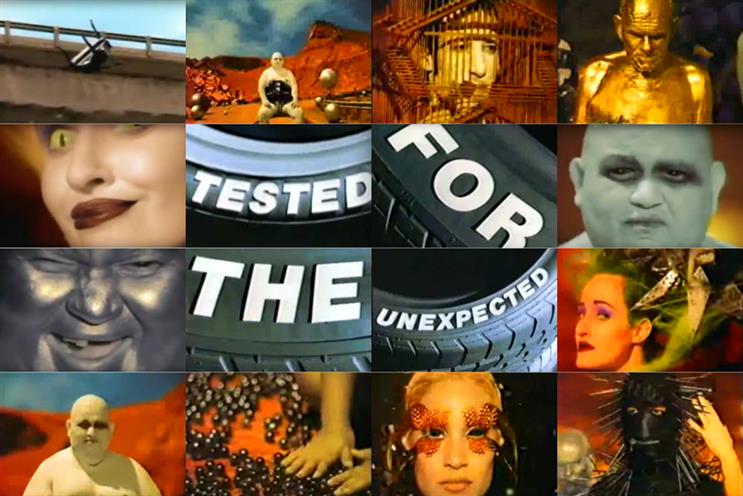

One of my favourite campaigns of all time is AMV’s extraordinary effort for Dunlop, back in 1993. It took a prosaic brief about being prepared for all eventualities and turned it into a surreal obstacle course, featuring falling pianos, rubber fetishists and an evil genie. The line was "Tested for the unexpected" and you can be pretty sure that this work was not anticipated by anyone, at the outset of the process. But you can also be fairly certain that it’s the only tyre ad from that year, which anyone still remembers to this day.

Maybe this is a challenge we should all set ourselves: a test for the unexpected? Is this idea exactly what we would have predicted before we set out – and if so, why do we think it will surprise anyone in the real world? Likewise: has this team added anything to our brief – and if not, why have we paid them all that money and given them all that time, just to parrot back what we gave them in the first place?

At its best, our industry is capable of creating huge commercial value, using such gloriously unexpected solutions as sarcastic aliens, pregnant men, drumming gorillas, subservient chickens, strutting superheroes and rainbow bootlaces. Let’s have more of these, rather than the equivalent of Ms Stein’s copulating canines.

Andy Nairn is the co-founder of Lucky Generals