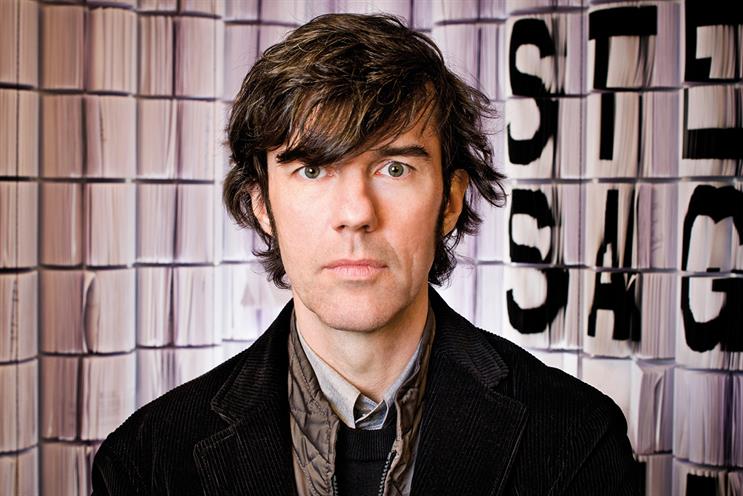

Just like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get with Stefan Sagmeister.

Unpredictability is the hallmark of the Austrian-born, New York-based iconoclast whose work, often as striking as it is unsettling with its innovative use of typography, has profoundly influenced design culture for more than a decade.

Even so, it’s surprising to learn that beauty will be Sagmeister’s theme when he talks at the D&AD Festival.

After all, this is someone who was prepared to self-harm in the name of art. In 1999, he created a lecture poster by having the details carved on to his chest with a knife.

For his 2003 "Sagmeister on a Binge" exhibition poster, he ate 100 different junk foods, gaining almost two stone in the process, and took "before and after" pictures of his semi-nude body.

Not exactly what you would call beautiful gestures. But Sagmeister acknowledges that age – he’s now 54 – is distancing him from his reputation as design’s "bad boy".

"I certainly don’t feel like a maverick and I’ve become much milder," he says, though insists: "It’s not that I’m losing my creative potency. I’m just trying to be true to myself."

Perhaps this personal catharsis explains his current obsession for beauty – a "subject close to my heart" and one he believes is back in vogue after a century of neglect.

He suggests beauty was the unsung casualty of the Great War. Having thrived since the Stone Age, beauty couldn’t survive the post-war hostility to it after four years of mass slaughter.

But more recent developments indicate a comeback – which is being reflected in everything from design

to architecture to the sciences, Sagmeister claims.

For evidence, he cites Google Books. Embracing more than 25 million titles, it is said to be the biggest online collection of human knowledge. "I’ve just seen a survey of all the online books Google has been digitising," Sagmeister says. "It’s clear from that survey that, while interest in beauty had been on a downward slope for a very long time, that interest has been steadily growing since about 2005." His conclusion: "Function can’t do the job by itself. It needs beauty to be relevant."

How all this will play out at the D&AD Festival, often seen as an uncomfortable alliance of designers and agency creatives, remains to be seen.

Sagmeister’s advantage is that he has had his feet in both camps. He spent two years working at Leo Burnett in Hong Kong, while Sagmeister & Walsh, the New York design company he co-founded, has a client list embracing Pepsi, Levi’s and Red Bull, and working relationships with agencies including Bartle Bogle Hegarty, Droga5, TBWA and Publicis.

Does he think the design and advertising disciplines can learn from each other? After all, both have been fuelled by technology. Indeed, Sagmeister singles out technology as the most significant factor in the advance of design, enabling its exponents to do things that would have been unthinkable 20 years ago.

Sagmeister, though, has his doubts. He points to Fallon London’s 2005 Sony Bravia commercial featuring 250,000 balls bouncing down San Francisco’s streets as a rare example of advertising elevating to the status of art. Budgets would have prevented such a film being made as purely a piece of art, he suggests.

What’s more, graphic designers and agency creatives still struggle to name the most influential figures in each other’s discipline. "Of course there has been some blurring of the lines, but they are still quite separated," Sagmeister asserts.

Nevertheless, design has undergone a huge rehabilitation since the 1990s, when low esteem threatened to decimate it, Sagmeister says. He suggests that’s partly because of a burgeoning interest in the discipline by a public that has come to realise that successful design is difficult.

"So many people used to look down on design, suggesting that making things beautiful is somehow less

valuable," Sagmeister argues. "That’s bullshit."

There is one thing, though, that Sagmeister believes creatives from any discipline could benefit from – taking sabbaticals. ±±ľ©Čüłµpk10 actually caught up with him while he was in Tokyo, where he is five months into his third year-long career break – a journey that began in Mexico and will end in a tiny village in the Austrian Alps.

He has previously admitted that his first sabbatical – taking no work from clients and not knowing whether or not they would remain loyal – was a "heart in the mouth" decision.

In fact, Sagmeister sets off on his sabbaticals with a loose schedule that gets refined as he goes along. He works hard each day – one current project is creating an exhibition that he wants to take around the world – but ensures his evenings are free to meet friends.

"Any creative in any situation can profit from a sabbatical but it does need a lot of planning," he warns. "Also, I’ve had students approach me about going on sabbatical. I say no. Sabbaticals will only be of benefit after you’ve worked a significant amount of time."

And what of Sagmeister when his latest odyssey finishes? A travelling exhibition focusing on another of his preoccupations – happiness – remains unfinished business.

As for the longer term, he has no idea what his epitaph will say. "I’d like to be remembered as somebody who was kind," he confesses. "Beyond that, I’ve not the slightest idea – and I won’t lose any sleep over it." How predictably unpredictable.