'Having a god complex is not only bad for business, it's also bad for creativity'

Have you heard the one about Graham Fink, one of the most celebrated creatives in advertising, turning up to the British Arrows dressed as Robin Hood, wielding an empty quiver in anticipation of picking up some awards?

Or Ron Collins, a founder of WCRS, who famously used to appraise student books using a foul-mouthed Sooty glove puppet?

And legend has it that Tony Brignull, one of the most awarded copywriters of all time, knocked out an account man for changing his copy, although this is disputed.

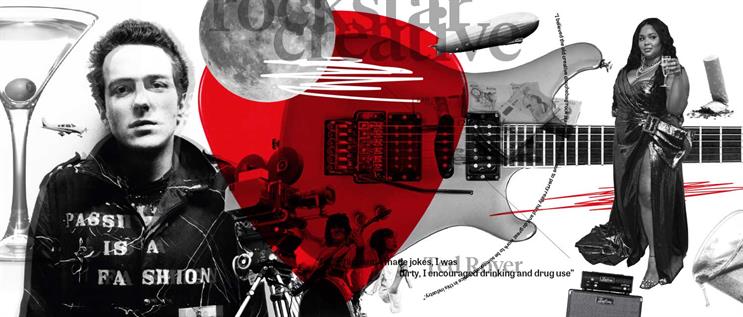

Such stories have become lore in the world of advertising: creatives known for their swagger, antics, eccentric wardrobe choices, office outbursts or all of the above. Their personas loomed large and their names were on the door. Uncompromising in their vision, they were the closest you could come in this industry to a rock star. Some say they just don’t make them like that any more.

That is one version, anyway. More recently, the dark side of so-called rock star behaviour has come to light. When Ted Royer, the former Droga5 New York creative chief who was fired in 2018 after an internal investigation, resurfaced last year at an event for young creatives in Las Vegas, he caused a stir for his remarks about his previous conduct: "I was flippant, I made jokes, I was flirty, I encouraged drinking and drug use. And I believed the old creative douchebag rock star notion that you have to party really hard and do great work to be someone of notice in this industry."

Many people have been happy to see that definition of a rock star die. In a column published in 北京赛车pk10 in January, Melanie Welsh, founding partner of planning agency Strat House, wrote that the rock star persona "has lost much of its fanbase".

"The rock star delusion has existed in part because senior creatives, who have tended to be white and male, have been one of the most adulated and cosseted groups in the history of this industry… They were the virtuosos, the mavericks. If they wanted to behave like a cross between Keith Moon and Little Lord Fauntleroy, who would dare stop them?" she wrote. "The irony is that having a leader (male or female) with a god complex is not only bad for business, it’s also bad for creativity."

In response to Welsh’s criticism, veteran creative Paul Burke hit back with the argument that "advertising always thrived on the talents of rock star creatives and we’ve all reaped the benefits".

"Do you like what the neutering – rather than the nurturing – of rock star creatives has done to your industry? Are you proud of the ads it now produces?" Burke contended. "Now, more than ever, we need rock star creatives to restore the swagger, glamour and cultural significance that made advertising such an important and enjoyable industry."

This is a debate worth examining in an industry built on talent. Practitioners who fret about a "talent crisis" are pointing to a real fear that this business can no longer attract or keep the best people, and is losing its relevance as a result. Some leaders with long careers and memories say it wasn’t always like this: advertising was cool and people wanted to work in it. So how much were rock star creatives responsible for that? Does the decline of the rock star mean the death of the industry’s creativity?

The term itself comes with a lot of baggage. A rock star, in the traditional sense, "was a free-spirited, convention-flouting artist/rebel/hero/Dionysian fertility god who fronted a world-famous band, sold millions of records and headlined stadium concerts where people were trampled in frenzies of cult-like fervor", writer Carina Chocano noted in a 2015 New York Times article. Yet in recent decades, the phrase has become a business buzzword to refer to any kind of virtuosity: you can be a rock star salesperson, marketer, programmer, chef and so on. "Pretty much anyone can be a rock star these days – except actual rock stars, who are encouraged to think of themselves as brands," Chocano wrote.

Those deemed rock stars in advertising have been the people who were at the top of their game, but who also took on some of the stereotypical traits of real rock stars: they acted up, they got noticed. Yet using this term also assumes a wider cultural relevance that advertising sometimes lacks, a countercultural spirit that could be at odds with business demands or a certain set of behaviours that are no longer accepted in the workplace. No wonder many people now reject the very idea of a rock star in this industry.

"The times have changed and the totems have changed. It’s a totally different industry than it was 20 or 30 years ago," Vicki Maguire, chief creative officer of Havas London, says. "You don’t want to go and work for somebody because they’re going to party hard. The environment and culture [of a workplace] are just as important."

A major reason for the aversion to the term "rock star" is that those who wore this label often fit a narrow description that no longer captures the full range of talent coming up the ranks. In advertising, as in many other industries, the traditional heroes are mostly white men whose names still hang on the doors of the most storied agencies. As the industry changes and makes room for more diverse voices, "there’s an entirely new breed of role model", Mel Arrow, head of strategy at BMB, says.

Echoing this dissatisfaction with conventional role models, Jess Geary, senior channel strategist at Rapp UK, adds: "The term ‘rock star’ leaves little room for neural diversity at the very least. Aren’t we sending a pretty clear message to our introverts, our norm core heroes, our empaths and very often our women that they aren’t as good or valuable?"

This shift in perspective is happening in wider culture as well. Rock stars look different these days – think less Mick Jagger, more Lizzo, who graced the cover of Rolling Stone in February and has become a superstar for her messages of body positivity and female empowerment. Hedonism and hubris are out, while social consciousness, community and kindness are in – in other words, "you don’t have to be a dick", Brendon Urie, lead vocalist of Panic! At The Disco, told Kerrang! last year.

Today "a rock star is someone who’s willing to take a chance and stand up for what they believe in, maybe before anyone else believes in it", Sam Carter, vocalist of British band Architects, added.

The Clash’s Joe Strummer’s dictum that "without people, you’re nothing" has bled into the world of business, including advertising. "I don’t truly believe that in this day and age people do this on their own," Richard Brim, chief creative officer of Adam & Eve/DDB, says.

"Rock stars can get in the way of other people because they have this omnipresent figure in front of them. The best ideas we’ve had [at A&E/DDB] didn’t come from the rock stars, but from people who felt empowered to say whatever they thought. The answer can just as well come from the quiet tech guy in the corner as it can from the vastly overpaid person in the centre of the room. The minute you go ‘that’s a rock star’, you’ll just listen to that person more than anyone else."

Instead, collaboration is seen as one of the most important values in the modern workplace. Take esteemed commercial director Dougal Wilson. "You couldn’t meet a less rock star person if you tried," Brim says. "He is so respectful of everybody and won’t stand for bad behaviour, but he sweats every detail and he’s a genius." Brim himself, along with Maguire, Leo Burnett’s Chaka Sobhani and Droga5 London’s David Kolbusz, among others, are prime examples of a new generation of industry leaders who have big personalities but do not fit the mould of egotistical and tyrannical creative directors.

Sometimes, however, a fixation on collaboration and consensus can come at a cost to truly bold work. Julian Douglas, vice-chairman of VCCP, recalls his stint at Bartle Bogle Hegarty when the agency was developing the 2002 Levi’s ad "Odyssey", directed by Jonathan Glazer. The now classic spot follows a couple running and crashing through walls – but before the idea was made, the client questioned how Glazer would be able to keep up the energy and interest. "[Glazer] just hit a point where he said, ‘because I’m good’. It was such a mic drop moment – from anyone else it would have been extremely arrogant, but because he was the rock star talent in the room, it ended the debate," Douglas says.

Today, such single-minded confidence in an idea is rarely enough to end debates when more people are involved in the creative process, Douglas believes. "I don’t think it was ever easy to make brilliant work, but perhaps there were fewer people to convince," he says. "Today everyone feels they can do it – you can cut a video on a phone, for example – so it’s quite hard to go, trust in my expertise. If everyone’s having a go, you’re going to get more mediocre work."

There is also more fear among clients and agencies increasingly under pressure in a more tumultuous marketplace, Douglas adds. "People tend to do things that are much safer, tried and tested and won’t rock the boat. There are far more rounds to approval now than there were in decades past," he explains. "The more rounds of approval and layers of an organisation an idea has to go through, the more it will be normalised, rationalised and safer. That’s led to a lot of things that make sense and work and are effective, but if anything it takes you away from those outliers that break the mould."

Dave Trott, one of the rock star creatives of the industry’s past that Burke named in his article, also believes that fear is having a negative impact on creativity.

"Every age of advertising is a reflection of what’s going on in the world around it. Now everybody is scared stiff to do anything controversial or get into trouble or be outrageous. Rock star behaviour is controversial, fun and outrageous. The whole point used to be to generate controversy in order that we generated more media. If we could get into trouble a bit, that was a good thing," Trott says. "Nowadays if there’s controversy, you issue an apology and hope no-one will notice. ‘Afraid’ is the big word. Then you wonder why it’s not rock star advertising any more."

But Trott and others also contest the idea that the most influential creative figures in advertising’s history always embodied bad rock star behaviour. John Webster, for example, was an unassuming character who "dressed like he was going to the allotment. He’d come in wearing a tweed jacket and scruffy boots and write ads that no-one in this country was doing," Trott recalls. "All of his creativity was in his work. He didn’t behave like a rock star, get drunk and throw stuff out the window. He loved his work and won more awards than anyone else."

Paul Silburn, the industry legend who died last year, "was incredibly humble and loved the work", Brim says. "Nothing came close to him, but I don’t think he ever walked like a rock star."

Advertising veteran Mark Denton explains: "The very best creatives didn’t chuck their toys out the cot. They were people like Webster or [John] Hegarty who were great at selling work, were great presenters, and had gravitas and the respect of the client. They had this fantastic body of work behind them that you just couldn’t argue with."

Denton remembers walking down the streets of Soho in the heyday of Gold Greenlees Trott, which was co-founded by Trott, and seeing the lights on in the agency’s windows even at the weekends. The creatives behind those windows embodied a passion and work ethic that Denton fears is getting squashed in today’s more risk-averse and high-pressured environment. He is among those industry veterans, like Trott, who say advertising creatives have lost some of the trust and freedom that allowed them to be prolific and make groundbreaking work.

"The fun bit as a creative was you used to get your work made. I meet young creatives now who haven’t made anything for two years – nothing. That’s why people are getting burnt out," Denton says. "As a creative, when you get your work bought, sold and made, there’s no drug like it. It’s more exciting than any of the bad stuff on offer."

At a top agency a few years ago, Denton recalls seeing an all-staff email in which employees were encouraged to never say no to clients. This is a far cry from a period when "it was encouraged for creatives to stand their ground. Creatives were given more licence back then, but for the best ones it was about the work, and the clients benefitted," Denton says. He believes creativity thrives in places that make room for disagreement and debate.

Nils Leonard, co-founder of Uncommon Creative Studio, agrees. "A great industry falls out. It’s okay to argue and have different points of view – that’s the best bit," he says. "We used to be more open to differences and collisions."

The industry is at a point where it is railing against the old structures and patriarchy, and rightly so, Leonard says. He can certainly relate to that disillusionment: "I spent many years following genuine heroes of our industry. But when you get close to your heroes, you kind of kill them by proxy. I learned from them but I also learned things I definitely didn’t want to do."

Such frustration propelled Leonard and his business partners, Lucy Jameson and Natalie Graeme, to start their own agency. He cautions against falling into cynicism when confronting challenges, and he is an outspoken advocate for the industry’s potential. "I don’t hate our industry but there are things about it that I hate. I take that as my responsibility to change them," he says. "You must take it personally enough to go and make change."

However, Leonard worries that in all the upheaval, people are losing sight of what was always good about this business: its talent. "For the past five years our industry has got very good at hating and finding villains. We’ve stopped sharing what we love and started sharing what we hate. We have lost sight of how to celebrate each other," he says. "That has gone missing and it’s a critical part of our game. You need to believe in people – people show us the way. Be fans of each other."

As Brim puts it, instead of rock stars we need "diverse creative beacons who inspire people into the industry". Every sector of culture, including advertising, has been shaped by such beacons, who dared to do things differently and motivated others to follow that example.

After all, think of the first time a so-called rock star captured your attention on stage or screen. It wasn’t the superficial trappings of their appearance or vices that captivated you – not really. You watched them because they were unapologetically themselves, they had something to say, and they wanted so passionately for others to hear it. As Leonard says: "You don’t just practice creativity, you have to believe in it. Belief is fundamental." A rock star, in whatever form they take now, is someone who compels you to believe.