In a recent psychological experiment, two groups of people were given an exercise. One involved words relating to youth and vitality, the other, to age and infirmity. The real experiment began only as they left the room. Those with words relating to infirmity still fresh in their minds moved much more slowly and uncertainly than those dealing with words relating to vitality.

In another experiment, two groups of students were given the CV of a new lecturer. It was exactly the same CV except for a few words. One said he was cold and aloof; the other said he was warm and friendly. Both groups attended a lecture by the subject of the CV and were asked afterwards what they thought of him. Those with the 'cold, aloof' CV said he was cold and aloof, and vice versa.

There are now thousands of experiments demonstrating just how open to influence human beings are. We are manipulated by examples of 'priming' and suggestion, such as those above. We fall prey to 'anchoring' and 'availability' (being more influenced by fresh or easily remembered information than by relevant facts). We are strongly swayed by the blandishments of authority, of social pressure (conformity, fashion) and by instincts of reciprocity (giving, trusting and liking). We are too quick to accept shoddy explanations without further investigation, so long as they make superficial sense.

Our perceptions also make a mockery of much of our decision-making. Our judgements about others are routinely confounded by emotional projection and transference. We give value in the hand disproportionately more weight than value we might have in the future; we feel losses disproportionately more than gains; we consistently overestimate our own abilities (including our ability to make good judgements); we are often strangers to our own selves, unable to predict what we will feel like when we are angry, hungry, drunk and so on.

Led by the superficial

We are also acutely sensitive to small changes in conditions, but very quick to adjust to these changes (leaving us without an 'objective' benchmark for decision-making), and we routinely make decisions based on superficial comparisons rather than objective facts. For example, in experiments, if you offer someone a choice between two products, one priced £8 and the other at £12, most will choose the £8 option. Yet, if you add in a third option at £20, without changing the quality or value of any of the choices, most will opt for the £12 alternative. Suddenly, the addition of another option changes our decision. The £8 option seems suspect ('if it's that cheap it must be shoddy') and the £12 option seems good value - a trick many brands and retailers have known for a long time.

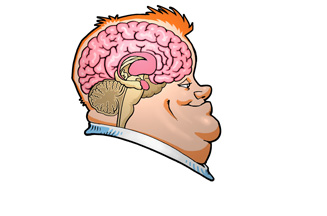

A revolution in behavioural, social and evolutionary psychology is rapidly mapping these and many more 'predictable irrationalities'. Meanwhile, neuroscientists are discovering the connections between these behaviours and the functioning of the brain. Now we can actually see which bits of the grey matter get fired up by which decisions, and even what chemicals are at work. For example, positive expectations of an experience release neurotransmitters such as endorphins and opiates, which actually make us feel good in anticipation.

What does this revolution mean for marketing? How could - should - marketers use this new knowledge?

One certain route to disaster is to view these discoveries through the lens of the mid-20th-century behaviourist psychology upon which most modern marketing theories are based. This teaches us that human behaviour is infinitely malleable: all you have to do is find the right 'stimulus' to get the right 'response'.

It is complete codswallop, but it sounds plausible and it creates its own research and action agenda: 'If we can find the correct stimulus, we can generate the right responses, and, hey presto, we will have discovered the secret of "effective" marketing. What better way to do this than by working out how the human mind works?'

Brain researcher Adam Koval expressed this approach perfectly a few years back when he said that new discoveries in psychology and neuroscience 'give unprecedented insight into the consumer mind. It will actually result in [marketers] getting customers to behave the way they want them to behave'. Before we get carried away by Koval's dream, however, let's dig a little deeper.

Punchbag marketing

First, there's far more we don't know than we do know. Yes, people may walk slowly after being exposed to words relating to age and infirmity. Yes, those students may have been influenced by what they read in the invented CV. Yet, how long do these effects last, how strong are they when mixed with other influences?

After a term of lectures, and students' natural tendency to gossip about their lecturers has had a chance to bear fruit, will their initial impressions remain unchanged? Influences like these may, sometimes, be strong enough to trigger a sale. The question is, are they long and strong enough to build a brand?

Now let us go one step further. If consumers are so easily influenced, every marketer is likely to pile in to use the same trick to influence them in the same way. To what effect? The net result is punchbag marketing (for more on this, see my blog) where, a), brands get sucked into an escalating arms race of short-term and superficial influences, with each brand's stimulus being quickly cancel-led out by equal and opposite stimuli, and, b), the consumer is treated as little more than a stimulus punchbag and so ends up punch-drunk. Is that really good marketing?

However, there is more, because human minds are complex and do lots of things at the same time. We are, for example, equipped with powers of foresight and hindsight; we can and do think through alternative scenarios; we can and do learn from our experiences. In one Stanford University experiment, consumers were exposed to advert-ising that appealed to certain cultural stereotypes. The advertising had a strong, immediate effect on preferences. However, when the same consumers stopped to think about their choices, the researchers report that 'this disparity disappeared'. So: outside the laboratory in real life, how influential would such advertising be?

Humans have other instinctive reactions, too. For example, one of our most finely-honed propensities is to look out for, and spot, deception and cheating. When we discover it, another overridingly powerful instinct kicks in - that of revenge. As mere mortals, we may be open to persuasion, but God help those who get caught trying to manipulate us.

There is one more dimension we need to consider. Every time we use energy generated from fossil fuels, we emit carbon into the atmosphere. Each emission seems small enough for us to ignore, especially when we look at the benefits created by consuming the energy. However, over time, these toxic emissions have accumulated and now threaten to cause catastrophic climate change.

Marketing tactics and strategies that deliberately take advantage of peoples' 'predictable irrationalities' also generate a toxic emission - of steadily accumulating, climate-destroying mistrust. Yes, taking advantage of these frailties may achieve short-term 'results' that make the marketing look 'effective'. Yet, the toxic emissions of mistrust just carry on accumulating to generate global climate change - an environment where regulators, the media and pressure groups think the words 'marketing' and 'ploy' go together as naturally as 'bees' and 'honey', for example.

So here is a prediction: over the next few years, new findings in psychology will trigger a fundamental rethink about what marketing does, and how. Marketers will be able to choose to use this know-ledge in one of two ways. Either they can set out to build deeper win-wins with their customers in more innovative and sustainable ways, or they can become more 'effective' in taking advantage of individuals' decision-making frailties.

The more we learn about human beings' predictable irrationalities, the greater the premium that society - consumers included - will place on those institutions, services, frame-works and methodologies that help us adjust, avoid and counter-balance their negative effects. Far from delivering marketers the elusive secret of effective influence and persuasion, ongoing discoveries in human psychology will actually expose advantage-taking, value-destroying marketing ploys to word-of-mouth revenge and punishment, and underline ancient (boring) marketing wisdom.

In the long term, brands are built by helping individuals make and implement better decisions, not by trying to take advantage of their decision-making frailties. In the long term, brands are built by consistently offering superior value that is delivered by fair processes, not by trying to hide mediocre value behind unfair processes.

The real question is how to do this. New research in psychology is transforming our understanding of human decision-making. We can use it to transform marketing too.

Alan Mitchell is a respected author and a founder of Ctrl-Shift and Mydex. Alan.Mitchell@ctrl-shift.co.uk

Debate your views

What impact do you expect our growing understanding of human decision-making to have on marketing techniques? How can you avoid accusations of exploiting consumers' frailties? Has the stimulus-response approach really had its day? How will you adapt your strategies and tactics?

Let's continue the debate - visit Alan's blog at