This year we’ve watched Facebook and Google be put through the wringer for their role in promoting fake news and offensive content.

This includes the interference of fake news in the 2016 US presidential election, to the recent investigation by into YouTube videos of undressed children that’s led to threats of a brand freeze, or that Russia-linked accounts meddled in the UK’s EU referendum vote.

The global proliferation of viral hoaxes facilitated through social platforms has helped expose the critical problem facing the digital advertising industry.

Fake news has become a highly profitable business. People (and publishers) are making a living off of viral hoaxes. Imagine you wanted to influence – or mislead – 1,000,000 people by getting them to visit a fake news site. You could achieve this goal by buying traffic for £0.15 a click. It would run you over £150,000.

That’s a lot of money.

But, what if you sold ads on your fake news site and could earn £0.20 for every visitor who clicked? And what if some of the content went viral? Now you’re netting at least £50,000, even as you mislead consumers.

Indeed, our data science team recently completed a study, , that examines these types of schemes.

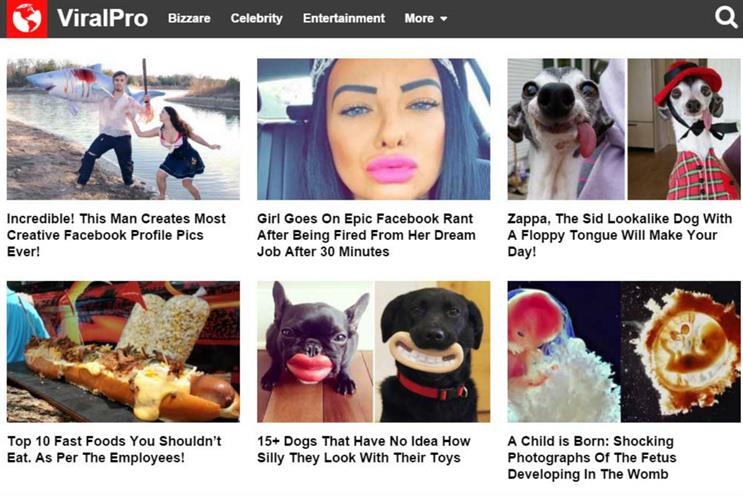

They found that viral content—subject matter that capitalises on people’s changing media consumption habits and shortened attention span—is a warning sign that a publisher is either knowingly or unknowingly purchasing fraudulent traffic for itself, or redirecting non-human users to other sites to drive monetisation.

Here’s how it often works: without a steady stream of visitors coming through their homepage, publishers who rely on viral social traffic experience major peaks and valleys in their revenue patterns. By manipulating people’s love for cute animals, playing on political differences, and their attachment to extreme ideologies, some firms have been wildly successful in distributing their content on social.

Even better for fraudsters, they’ve been able to generate ad revenues off of low-quality posts that require far fewer resources than properly fact-checked news stories or a professionally-made video. When their content fails to gain traction with social audiences, these publishers are incentivised to buy traffic from third-party sources that aren’t always legitimate because their success hinges on their ability to pay as little money for traffic as possible.

In addition to the overlap between viral content and ad fraud, our data scientists found a significant connection between viral publishers and the "fake news" content that dominated the conversation in the months prior to and following the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

In fact, our data scientists ultimately came to the conclusion that fake news is a subcategory of viral content rather than its own breed of storytelling.

Like other viral content, these ideologically-slanted, factually-dubious stories exist to get readers fired up, engaged and clicking – as we saw throughout the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the EU referendum vote here.

Some of these publishers don’t care why a reader would click; all they care is that they did click. Many ad-supported fake news publishers are more motivated by ad money than by ideology.

It’s time to end the cat-and-mouse game between fraudsters and legitimate actors in digital advertising and work towards a solution to eliminate ad fraud.

Industry-wide efforts like IAB’s Trustworthy Accountability Group and ads.txt have shown the resolve needed to work together to eliminate shady publishers from the supply chain.

Now our industry needs to address the grey areas of handling viral content fraud.

What happens when viral content attracts a mix of human and non-human traffic? What happens when an audience composed of real people is flocking to low-quality "fake news" content?

Answering these questions is the necessary next to solving this problem.

Nigel Gilbert is vice-president of strategic development EMEA for AppNexus