Start at the end. That’s the advice from a new book, The Last Mile, which explores how to nudge people into buying a product.

The author, Dilip Soman, a marketing professor at the Rotman School of Management, argues that advertisers are obsessed with getting people to love their products rather than actually buy them.

"Most organisations tend to pay the least amounts of effort to the last mile and spend a disproportionately larger amount of effort on ‘first mile’ issues such as strategy, innovation and branding," he says.

Soman adds: "This is probably why we end up with puzzles such as: why do more than 90 per cent of new products fail? Or why do consumers who say they are delighted with a product or service not repurchase it? The book makes a call for a better theory of the last mile."

His view was supported by Ogilvy & Mather Group UK’s vice-chairman, Rory Sutherland, at a recent Ogilvy event. Sutherland said the best advice he received in the early part of his career in direct marketing was to "start with the coupon".

This approach forces you to think about – and remove – obstacles for people to buy. Sutherland likened it to managing a traffic jam: if a road has bottlenecks at two points, there is no point widening the road at the first, because you would just create a bigger problem at the second. "The theory of constraints says the obstacles to remove first are the ones at the end," Sutherland said.

Here are the key lessons from Soman’s book.

Context is everything

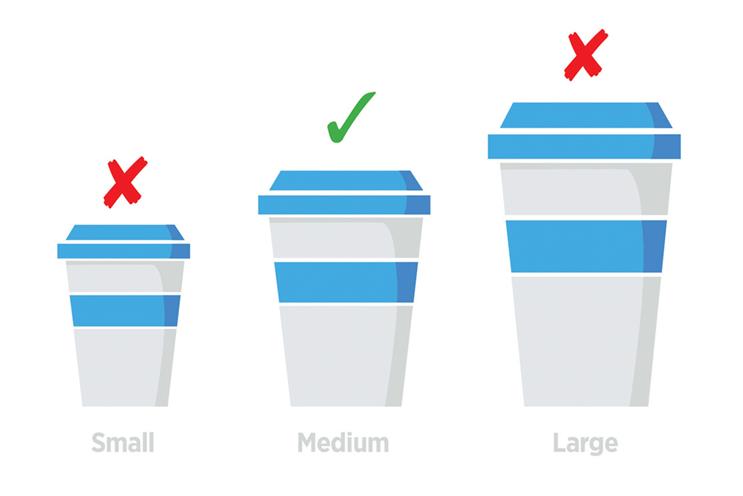

Research carried out by Soman on cup-size choices in 700 coffee shops around the world found that 74 per cent of cups sold were medium-sized. This is despite the fact that the volume contained in the cups changed depending on the shop – so the way choices are presented make a huge impact on how consumers behave.

Soman’s advice for retailers is to ensure they are effectively using their data to understand how consumers behave in the context of their own stores: "Map out the decision-making process and identify all the possible walls that could prevent consumers from making the purchase. Then think about the underlying psychology and see how best you can break those walls down one at a time."

There can be too much choice

When the restaurant chain Old Spaghetti Factory increased the choices on its menu, it actually reduced the number of options people ordered. "We believed that giving people more choice is good and that the more we can empower consumers with information, the better off they are," Soman suggests. "Neither is the case. People tend to completely ignore information when you give them a lot of it."

Value is a changeable concept

Another experiment in a Colorado ski resort found that the physical format of the ski pass had an impact on how frequently people visited the slopes. Everyone had to pay for a non-refundable, four-day pass in advance. Those who were given one card that they could use every day visited the slopes less than those who were given individual coupons for each day. "No matter how bad the weather got, those who had coupons still showed up," Soman says. Unused coupons remind people of lost value. He suggests this knowledge could be used to help nudge people towards healthier choices. For example, health companies could give people coupons to increase take-up for annual check-ups and flu jabs.

A penny saved isn’t a penny earned

Soman says: "Economists have long believed that money is fungible – that’s a fancy way of saying that any unit of money can be exchanged with any other. But our work has shown that’s simply not true."

Take the Boots Advantage Card. Those who save up points tend to spend them on luxury items such as perfume rather than day-to-day products such as toothpaste, even though the monetary value is the same.

"People spend money differently as a function of how it is earned. Salaries are treated differently from cash gifts; monthly incomes are spent differently from annual bonuses," Soman points out. "Also, money is spent differently as a function of how it is budgeted. Money that is designated spending money is going to be spent, even when the products you intended to purchase turn out to be cheaper than you expected."

If brands can frame a purchase as coming from a certain fund, people will spend accordingly.

Furthermore, the average spend on card payments is higher than that in cash. "The way in which you pay changes the way you consume. The easier it is to see how much money you are spending, the more painful it is to spend it," Soman says.

Think about the timing

"You are four-and-a-half times more likely to buy clothes if you touch them," Soman explains. "That’s when you know shoppers are interested, so that’s when you should approach them."

However, if a customer who was initially "just browsing" encounters a long queue at the till, this will give them time to remember they weren’t planning to buy anything and abandon the purchase. Soman concludes: "The psychology of time has immense implications for how we can manage waiting times, lines and, in general, consumer experiences."