Mr Cadbury, Mr Sainsbury, Mr Marks, Mr Spencer, Mr Lewis, Mr Boot, Mr Walker, Mr Sharwood, Mr Warburton, Mr Lipton and Mr Tetley. All were 19th- and 20th-century entrepreneurs who made their name by making their name into a brand.

Wherever you go in Britain, you will be near the birthplace of such a brand. Some of them made it big, some didn't, and some never wanted to. From brewers to shopkeepers, chemists to confectioners, the names are part of our tradition.

In the course of writing this book, we have been lucky enough to interview representatives from brand dynasties that go back one generation - in the case of James Dyson - and considerably further, to a great-great grandfather in the case of Jonathan Warburton.

One piece of combined learning is very clear: contrary to what you might expect, those who inherit a brand legacy can be just as fanatical as those who start one. These individuals, too, have something to prove and to live up to and, perhaps, even more of an ethos to uphold.

What, we ask, is the link between having one's name over the shop, on the side of the truck or in the hands of the millions who are buying your goods? Does proprietorial nomenclature define the brand, or does the brand make the proprietor?

This may be a tradition that is dying out. The new generations of brand-builders favour a different approach, keeping their name one stage removed from the business. Pret a Manger, Virgin, Innocent, Carphone Warehouse (not to mention Google, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft) are shining examples: the founder may be synonymous with the brand, but they are not eponymous.

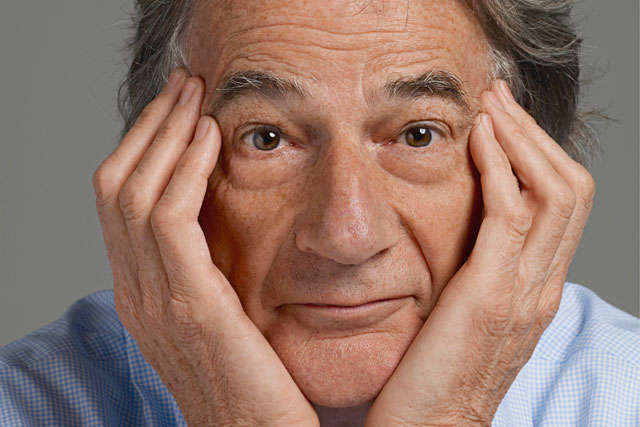

Just in case they have some wisdom to impart, we thought we would talk to some of the eponyms while they are still around.

Here, Marketing highlights some of the insights in The Branded Gentry: How a New Era of Entrepreneurs Made Their Names, offered by three of the 12 interviewees: Sir Paul Smith, Sir James Dyson and Jonathan Warburton.

Here, Marketing highlights some of the insights in The Branded Gentry: How a New Era of Entrepreneurs Made Their Names, offered by three of the 12 interviewees: Sir Paul Smith, Sir James Dyson and Jonathan Warburton.

SIR PAUL SMITH ON...

... taking early risks

I knew the danger: the job always changes you and you never change the job. I was very conscious of that at the beginning. I'd seen a lecture by Edward de Bono, and he made me think that if you want to stop this happening and stick by your guns, you've got to work out a way. You've got to somehow keep your purity but still get your income, even when each pulls you in an opposite direction.

[Our] little shop in Nottingham was 12ft2 and it was originally full of clothes that were unprofitable because they were very specific, especially for a provincial town.

So I thought, how would Edward (de Bono) work this one out? Should I change to selling clothes that people ask for? But that would mean me watering down the pure malt.

If I'd done that, I probably wouldn't be sitting here with you now; I'd probably be fat and just have my shop in Nottingham. So I decided to earn money on five days of the week selling fabrics and suits, and keep the purity of the stuff I wanted to sell for the Friday and Saturday.

Suddenly people started coming from all over the country to Nottingham, because you couldn't get anything like that anywhere else outside London. We were an oasis in the middle of the country. That's how I got going.

The reason why I've done all right is because I've always worked out a way of having product or income from more commercial things while still being really respectful of image, exclusivity and special things and limited editions.

... finding inspiration

Facebook, tweeting, blogs; I mean, I completely get it, and we have a whole department in marketing alone doing this kind of modern-company thing. But, personally, I'm a real pen-and-paper guy.

I like the idea that when you do something with a pencil, you can make a mistake and from that mistake can come an idea.

... work ethics

Things are very tough, especially now. What you hope is that the younger generation will see what's happened and might still be bright enough to readjust and understand what life on earth is about.

We all enjoy having some money and we all enjoy the opportunity to buy something special, but let's keep it within reason.

What's so horrible is that sometimes it's down to just one man sitting in his Porsche with his mobile phone, pressing a button that makes shares gain or lose millions. Whereas, take my guy who opens our warehouse and has been with me for 25 years. He opens it at nine every morning, whether it's snowing or not. He deals with 90 people, and when they're not feeling well and one's had a baby or had a bit of a problem with their heart, he deals with it.

I remember one designer asking me: 'How come you've done so well in Japan and how come that your clothes look so good? They made some handbags for me recently and they were nothing to do with our style at all.'

So, I said: 'Well, how often do you go each year?' The answer was that he had only ever been once, ever; he never even sent them a fax. I was going four times a year; I've been 85 times; I like the people, their heritage, their tradition, their food, and the jetlag doesn't worry me.

I've done well in Japan because I just got on with it. I like the Japanese. They embrace me, I embrace them, I work 17-hour days, 14-hour days, and I'm very willing. It's a proper, honest partnership.

... the lure of money

My approach has always been that, if I can just have a nice day, that'll do. Now, the shops have done OK, and it's all grown, but it was never about anything more than that.

The thing is, if I've got £100m today, £50m, £25m, it wouldn't make any difference to my day at all. I don't want a private jet or a yacht: I've got love, I've got health and I've got freedom. I mean, obviously, there's the security; the fact that you know where your next meal's coming from, that you can be a little bit indulgent in terms of beautiful things. We own some nice paintings and my wife has a nice art studio where she paints for her own satisfaction, but she doesn't try to sell it and she's quite shy about it.

I'm not motivated by the money. I've got a house in Italy, but I just drive a Mini.

SIR JAMES DYSON ON…

... the joy of selling

(As a nation) we despise selling; we despise salesmen, whereas in America, it's a very esteemed profession.

But, in time, I discovered that selling is absolutely fascinating. And exciting - because when you get a sale, it's absolutely thrilling.

Also I found it really interesting to under-stand what people wanted. Selling isn't about talking - it's about listening; about asking questions.

... innovation through failure

Everything, or almost everything, I do fails. It's a bit like long-distance running: you start out not knowing where you're going to end up. You start with an idea, you develop it, you develop it and you develop it, and it is failures all along. Eventually you end up in a place where you had no idea you would be when you started.

We didn't actually set out to design a hand-dryer. We were developing something else and just noticed how it scraped the water off your hands.

So we immediately saw that it would give us a better hand-dryer, because it was fast, it didn't use the energy of a heater, and it didn't damage your hands.

What we're always searching for is that magic technology that makes something work better and solves the things you get angry about.

...others' views of Dyson

I believe the engineering is the most important thing, so all we worry about here are our next inventions; what we're going to do. That's all we have to worry about. We don't worry about what other people think of us; we don't have to worry about what investors think. We just have one thing to worry about, and that's the technology.

JONATHAN WARBURTON ON...

... attracting the best talent

My dad was never a great advice-giver, but one of the things he said was to surround yourself with people who are better than you - just don't necessarily tell them.

If you look at a lot of very successful people, behind them, in front of them or by the side of them will usually be some very, very able professional managers.

Those kind of people are attracted to an environment where they see long-term thinking, well-invested. That is what we try to do and need to continue to try to do.

... doing it differently

Our premise has been to do the opposite of everybody else. At one time, we were the only plant-baker in the country that didn't make private-label. Why would I want to do private-label, because the cost base is higher anyway? So that wasn't some kind of great strategic thinking.

We saw our future in building a great brand that had our family name over the door. To some extent, it's self-fulfilling; because you're far more bothered if it's your name than if it's another name. I couldn't work for anybody else.

I've been a non-exec director of a couple of businesses for a long time and I've found them fascinating, interesting and hopefully helped along the way, but I view them so differently than my own business with my own name.