Philippa Foot lectured on philosophy at Oxford, UCLA, Berkeley and MIT.

In 1964 she proposed a thought experiment in ethics.

(It isn’t supposed to have a right answer, it’s just supposed to provoke thinking.)

Suppose you were standing by the points on a railway line.

The points are there to switch the trains between the main-line and a siding.

On the main-line four men are working.

On the siding one man is working alone.

Suddenly, coming down the main-line, you see a runaway freight car.

If you do nothing the freight car will run straight into the four men and kill them.

If you switch the points, it will go onto the siding where the man is working alone.

You’d save the other four men, but the freight car would kill him.

The question is: what would you do?

Do nothing and four men die, or pull the switch and one man dies.

As I say, there isn’t a right answer.

But, in research, most people agreed it’s better to save four lives than one.

They agreed the right thing to do was to pull the switch and divert the freight car onto the siding.

But when those same people were asked if they would pull the switch they said no.

Even though they agreed it was the right thing to do they wouldn’t, or couldn’t, do it.

What we think and what we do can be very different things.

This dichotomy is illustrated by two great philosophers: Jeremy Bentham and Immanuel Kant.

Bentham was the founder of Utilitarianism: the greatest good for the greatest number.

To Bentham, saving four lives was obviously better than saving one.

It gave a net benefit of three lives.

But for Kant that wasn’t true, the act involved taking life and that’s always wrong.

Kant was the founder of the Categorical Imperative: the belief that every act you do should be something you would wish to be a worldwide law.

Killing people just because we think it will benefit others couldn’t be such an act.

And we can see Kant’s position makes sense.

But we can also see that Bentham’s position makes sense.

So which is the right one?

Again, whatever Bentham and Kant think, there isn’t a right answer.

If two of the greatest philosophers can’t agree, what chance do ordinary people have?

No wonder there’s confusion: we can see the sense in killing one man to save four, but when asked if we would do it the truth is no we wouldn’t.

So we can’t even be trusted to behave in a way we say we think is rational.

Yet when conducting research groups, researchers view respondents’ answers as facts.

Often creative work will live or die on what people say in research.

Groups of people are asked how they would behave in certain circumstances.

And their answers are treated like scientific findings.

Despite the dichotomy between what people say and what they would actually do.

Despite the fact that we know the two are often very different.

But we continue to ignore the fact that theory isn’t real life.

Or as David Ogilvy put it, "People don’t think what they feel. They don’t say what they think. And they don’t do what they say."

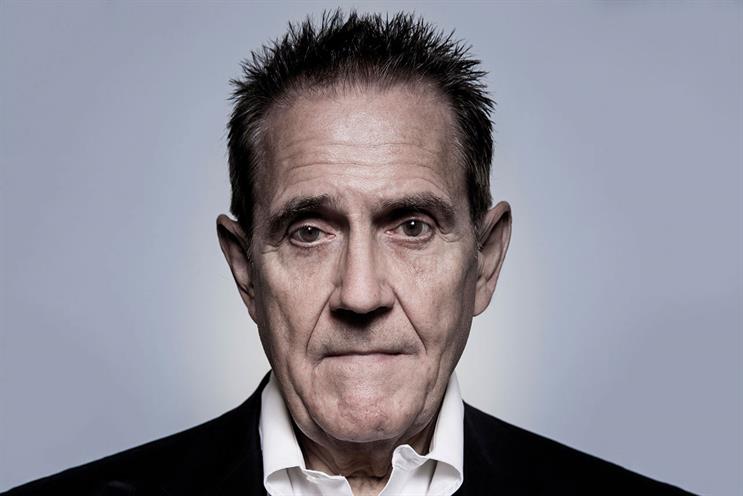

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three.