Editor's note: Addressing our Nigel Farage coverage

"The advertising industry is a great industry. They still go to lunch. They like a drink. There are some very clever people in it. It’s not heavily regulated, which means you can make money. I might fancy it myself one day," says Nigel Farage, leader of the Brexit Party, a "pound shop Enoch Powell" in the eyes of Russell Brand (a pound shop Oscar Wilde) and, according to The New York Times, "the most dangerous man in Britain". He laughs when reminded of this headline: "I loved it. I’d have paid for advertising like that."

Farage is holding forth with 北京赛车pk10 in a meeting room at Global Media and Entertainment’s headquarters in Leicester Square, shortly before he is to host his LBC radio show. On air Monday to Thursday evenings (from 6pm to 7pm) and Sundays (10am to 1pm), he now attracts 536,000 listeners (it is also watched online and on social media), an increase of more than 300,000 since the programme was first broadcast nationally in 2014. Today’s headline topic is fox hunting. "I like fox hunting," he says with a laugh, but then corrects himself. "I like the debate about fox hunting – and I like the idea that government shouldn’t regulate whether we hunt foxes or not." He is a regular attendee at the Boxing Day meeting of his local hunt at Chiddingstone Castle in Kent, partly, he jokes, because it is the only place in the county where you can get a pint at 10am.

Farage laughs a lot during the interview, usually at his own one-liners. He does so with such gusto it is hard not to laugh along with him as he explains what, in his opinion, is wrong with the advertising industry, how British politics is on the verge of a historic realignment and why the Brexit Party is set up as a company, not a political party. His trademark tweed jacket has been replaced by a businesslike, light-grey suit. The handshake is firm and friendly, rather than bone-crushing. Farage’s conversation verges on knockabout comedy at times and yet reveals a man who has thought more deeply about British politics than his "man at the golf club bar" shtick would suggest.

So what does Farage think is wrong with the advertising industry exactly? "They are so establishment, metropolitan and Londonised – they’re all in Soho aren’t they?"

"And Shoreditch," 北京赛车pk10 adds.

"Ah yes, Shoreditch," he nods. "And some of them are in Manchester, although they wouldn’t be there if they weren’t supported by taxpayers’ money. But they can’t see beyond London, which is why they missed a massive market opportunity. To be fair, they weren’t the only ones – the polling industry was slow to grasp this too – but, although some of my friends in the industry told me privately they favoured Brexit, every agency that commented publicly was pro-Remain."

Farage doesn’t fit our preconceptions of innovators. He is no Steve Jobs. Yet love Farage or loathe him – and it is a measure of his success that few are indifferent to him – Farage has been as transformational in his field, turning what once seemed a quixotic cause, the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union, into something 17.4 million of his compatriots supported at a referendum.

Farage’s success has prompted much agonised soul searching in adland. Mark Borkowski, founder and head of PR agency Borkowski, admits to getting acid reflux when discussing Farage and thinks Brexit is a salutary reminder of how inward-looking advertising and marketing have become. "All those people who were running around at Cannes recently, slapping themselves on the back and giving awards to campaigns that, as good as many of them are, play to hipsters in Shoreditch, Glasgow and Manchester, should give Farage a communications award," he says.

"When PR companies or ad agencies work with brands, we have become accustomed to adding layers to what we do to make sure the message works across every channel and adding nuance to make sure we reach every niche audience," Borkowski says. "Yet here is a man who understands his core audience, knows how to reach them, has the skin of a rhino and one very simple message." It doesn’t take much effort to remember "Take back control", a slogan Farage didn’t invent but co-opted when he recognised its potency.

Traditionally, political success of the kind Farage has enjoyed is attributed, at least partly, to a Machiavellian manipulator (think Peter Mandelson, Dick Cheney) or a spin doctor (Alastair Campbell, Bernard Ingham). Yet Jeremy Sinclair, chairman of M&C Saatchi and responsible for many political advertising campaigns, including the legendary "Labour isn’t working" poster, suggests Farage is different. "I don’t think he takes advice. He is seen as saying what he thinks, which plays to the mood of anti-political correctness in this country. He seems unreconstructed, slightly old-fashioned. How often do you see people in the media smoking a cigarette these days? Or drinking a pint of beer? He has positioned himself as the kind of bloke you’d talk to in a bar."

It has taken 27 years for Farage to become an overnight success. In 1992, he quit the Conservative Party in disgust at the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, which he believed fatally compromised British sovereignty. Seven years later, he was driving around the country with a UKIP poster that read: "Economic and monetary union means even more unemployment. Say never now." He became UKIP party leader in 2006 and, after victory in the 2016 referendum, left, saying he wanted his life back. Perhaps he realised that many voters agreed with David Cameron’s description of UKIP as "a sort of bunch of fruitcakes and loonies and closet racists mostly" or he had just tired of the vicious in-fighting for which the party was – and is – notorious.

After a spell on the sidelines – during which he may have lobbied Donald Trump to make him British ambassador to the US – punctuated by regular appearances on the BBC’s Question Time, Farage returned to the fray as Brexit Party leader in January. His mission, as he saw it, was to save Brexit, prevent the betrayal of 17.4 million Leave voters, arguing that "for a civilised democracy to work, you need the loser’s consent".

Winning 30.5% of the vote – and 29 seats – at the European elections was remarkable for a party that was only founded last November. That said, regional results do tend to confirm one official Vote Leave campaigner’s observation that "Farage is toxic within the M25". The Brexit Party won 17.9% of the vote in London – and just 14.8% in Scotland. Yet outside the M25 and south of Hadrian’s Wall, Farage is a vote-winner.

Brexit and the Brexit Party are supported by what he calls "real people", which implies that the 48% who voted Remain are unreal. This is, in his view, not as damning as how the media have portrayed Leavers. "The ad industry, like the media in general, has helped to perpetuate the myth that everyone who voted for Brexit were knuckle-dragging, tattooed, working-class scum," he tells 北京赛车pk10. "These people have no idea about what’s really going on in people’s lives." Given that some agencies responded to the Brexit vote by touring Britain on roadshows designed to understand this strange new zeitgeist, he might have a point.

"The emotional core of Farage’s appeal is unfairness," James Murphy, co-founder of Adam & Eve/DBB, says. "In 2016, the message was that you are being cheated by the EU. In 2019, the message was that the political elite is cheating you out of your referendum. It’s a very simple, emotive idea. They learned from the £350m-a-week-on-the-bus controversy not to bother too much with facts and to stick to emotions."

"Take back control" is usefully vague and uplifting, implying a sense of rightful ownership that needs to be restored. It’s hard to resist. What voter would say "You know what? I’ve had enough control, you can take charge for a bit"?

All this should come as no Damascene revelation to the advertising industry. Six years ago, a study for the IPA found that the most effective campaigns of the past 30 years in the UK were those with "little or no rational content". As ad strategist Ian Leslie wrote in the Financial Times: "Ads imprint themselves on the cortex when they touch the heart."

The other old-school advertising virtue Farage embodies is consistency. Sam Delaney, author of Mad Men and Bad Men: What Happened When British Politics Met Advertising, says: "He understands the importance of saying the same thing hundreds of times because the moment you’re really bored with it is the moment it gets through."

Staying on message is easier for the Brexit Party, which is registered at Companies House as a private company rather than a political party – the same route taken by Italy’s Five Star Movement, from which Farage has learned so much (see below). The Brexit Party has only three active directors – Farage, chairman Richard Tice and corporate financier Mehrtash A’zami – and is organised that way because, its leader says: "I thought I might as well stand or fall on my own ideas rather than something decided by a committee on a Friday evening after a six-hour meeting. That’s why we set it up properly as a business – and I own 60% of the company."

This model gives the leadership the freedom to vet new members – as the history of UKIP proves, you never know when a closet racist is going to decide to come out – and manage debate. In Delaney’s view: "The reason he fell out with so many UKIP members so often is because he rode roughshod over them."

With the Brexit Party set up as a kind of detoxified, professionalised UKIP, Farage is much better placed to keep everyone on message. And when you boil it down, that message is even simpler than "take back control" or "change politics for good"; it is us against them. Just as Five Star co-founder Beppe Grillo rose to fame by attacking Italy’s notoriously corrupt political caste, Farage made his name by attacking the EU, an organisation that, according to countless tabloid front pages, was determined to ban curved bananas and regulate how much cleavage barmaids could display.

"He has found a political space that suits him," Helen Thompson, professor of political economy at Cambridge University, says. "He understands that his core audience doesn’t want to be patronised by politicians and he shows that desire himself. He’s not as instinctive a politician as Trump but is good on the attack." And the real or imagined excesses of the EU – particularly the European Parliament – have given Farage plenty of ammunition.

While firing his tactical bullets, Farage has never lost sight of his strategic goal, which, Benedict Pringle, founder of Political Advertising UK, says, brands should learn from. "He has always had a simple yet unreasonably ambitious objective. The idea that the UK might leave the EU was almost unimaginable at the turn of the century but through relentless focus, personal charisma and a dollop of luck, he has almost achieved it," he says. In his own way, Farage has followed David Ogilvy’s oft-quoted advice: "Don’t bunt, aim out of the ball park, aim for the company of immortals."

That was the British advertising industry’s credo in the 1970s, when clients trusted agencies and agencies trusted their creative directors, but Delaney says: "From my experience of working with brands today, most campaigns start out as an exercise in damage limitation. The first goal is not to offend. And if something does offend even a handful of people, brands lose their nerve and give in."

Borkowski agrees: "One of the things that Farage and Boris Johnson understand is that no matter how bad things get, if you stick it out, in a few days the narrative will have moved on. If a brand gets criticised, the immediate instinct is to hide when, sometimes, they would be better advised to just tough it out."

The "Breaking point" poster is a perfect illustration. Showing migrants queuing to cross a border in the EU, the poster was unveiled on 16 June 2016, just hours before Labour MP Jo Cox was shot and stabbed to death by someone shouting "Britain first." The then chancellor, George Osborne, likened the poster to Nazi propaganda. Official Vote Leave campaigners despaired. The poster, it was agreed, had clearly backfired. Yet had it?

The furore kept immigration – an issue Farage had always regarded as motivating voters to back Brexit – in the spotlight for days. One week later, voters shocked the establishment – and quite possibly themselves – by voting to leave the EU. The poster was – and still is – shocking, but it was the kind of outrageous ploy that Grillo had used to dominate the political and media agenda in Italy.

"Farage is not universally appealing – Vote Leave decided to ostracise him in the referendum because they felt he wouldn’t help them get past 50% of the vote," Pringle says. "But what he has done is pick an audience, delight them and he’s not tried to placate everyone." Farage’s approval ratings have never been high – they hover around 24% at the moment – but, as Pringle says, a "significant minority of dedicated supporters is plenty" if you want to drive change.

The concept of authenticity may have become unhelpfully ubiquitous but it is at the heart of Farage’s appeal. "What he has done is develop a set of distinctive and authentic brand assets and sweated them," Pringle says. "The tweed jackets, the photo op in the pub, the open-mouth cackle and the shouty style of speaking, these are all ownable and ring true for him. Too many brands go astray by trying to adopt the values of the moment."

A lover of gin, beer and pork chops, five-day cricket matches, John Buchan’s thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps and World War I battlefields, Farage is so British he almost seems like a caricature. Yet as he says: "I am what I am. People’s attitudes are changing. People appreciate authenticity – look at Jacob [Rees-Mogg], Ann Widdecombe, Trump. They accept people who are flawed like me because we all are – I mean, look at Boris, he makes the rest of us look like vicars!"

Consultants have suggested that Farage change his image, even feminise himself. When reminded of this, he laughs out loud. "I mean, come on," he says, before finding himself – unusually – at a loss for words. Does his image or brand matter to him? He shakes his head. "I don’t look backward, I don’t read anything that is written about me." A later remark that he was treated disgracefully by the media between 2014 and 2016 suggests he may be being economical with the truth at this point.

Sinclair says Farage is right to stick to his guns and not rebrand. "That is absolutely the last thing he should do. What I take from his success – and it’s something that all brands can learn from – is you have to be who you are, not who you might like to think you are."

Who is Farage really? He comes across as a crusader – a challenger brand, if you will – but critics say he’s just a career politician who has made a career out of attacking other career politicians. Yet, as Sinclair says, he is not without charm, personality or wit. In a profession noted for pomposity, his humour can get the message across. Such one-liners as "France is wonderful. It should be. We subsidised it for 40 years," enthral his supporters.

To be fair, he doesn’t just laugh at his own jokes. As a man whose career depends, in part, on his ability to work a room, "Mr Brexit" (as he is referred to in his LBC profile) is a master at projecting bonhomie. Delaney once tested this by bestowing a mock knighthood on Farage on his News Thing RTUK TV show. At the end of the ceremony, the girl, a trained actress, who had "knighted" him, says: "My mummy says you don’t like foreigners." As Delaney recalls: "He didn’t get angry, he just went red and said something like ‘Oh I wouldn’t say that.’" Yet what happened next amazed the broadcaster. "He came over laughing and shook my hand. People began sharing the link – and then he shared it. It was everywhere. He really understands that any publicity is good publicity as long as they get your name right. If you have a go at him, you realise that the harder you are on him, the louder he laughs."

Yet there is another side to Farage’s hearty demeanour. "He has learned from Five Star in Italy how to bludgeon the media," Murphy says. "He gets so much airtime on Question Time because he has, with the help of the tabloid press, cowed the BBC. The focus on the media as biased servants of the liberal elite is relentless."

Similar ambiguities surround his "man of the people" image. His father, a stockbroker and antiques dealer, sent Nigel to the public school Dulwich College. Before politics consumed his life, Farage earned his keep as a moderately successful commodities trader. He now earns more than £25,000 a month for his media work through his company, Thorn in the Side, a name that says a lot about his self-image. His sons, Thomas and Samuel, have made careers in the City. It takes some nerve to sell yourself as anti-establishment when you’re an ex-public schoolboy who has worked most of your life in finance, but Farage pulls it off for a subset of voters. He has calibrated his image carefully, coming across as a genial member of the middle class.

Yet the real Farage must be more complex – and more interesting – than he lets on. He had the vision to understand, sooner than most of his British rivals, the transformational political power of social media. "He has an old-fashioned, mass-market message but he delivers it using state-of-the-art technology," Murphy says. Unlike most politicians, he is happy to discuss the techniques he has used – and where he learned them.

"I worked for American companies for 20 years and I travelled across America a lot. I saw the change – social media – happening more than 10 years ago. Remember Howard Dean [the former Vermont governor credited with creating the first political meme] in 2004? That was the first time it happened. Obama did a brilliant job in 2008, flouting every regulation, but he got away with it because he was a liberal," he says with a laugh. (For the record, the fact-checking site Politifact concluded that while there was a "strong equivalence between the way Obama and Cambridge Analytica accessed user data on Facebook", the critical difference was that users knew they were handing over data to a political campaign in Obama’s case, whereas with Cambridge Analytica, users thought they were taking a personality quiz for academic purposes.)

After studying what Five Star and its internet guru Gianroberto Casaleggio did in Italy, Farage has put similar methods to use in the UK. It can be no coincidence that one of the Brexit Party’s new MEPs is Alexandra Phillips, who worked at Cambridge Analytica, where Steve Bannon, a sometime confidant of Farage and Trump, was vice-president for a time.

The Brexit campaign replaced the traditional model, which treated the online audience as passive recipients of messages from leaders, with something more collaborative. Users felt like they were part of a conversation, a movement, and were encouraged to become paid "supporters" by a constant stream of varied, engaging content.

"I wanted UKIP to do social media but they wanted to stick to traditional methods," Farage says. "Yet social media has worked for the Brexit Party. We raised £3m in a few weeks and we’ve launched our first consultation – we had 32,000 responses to our survey in 48 hours, which shows how committed our people are. We’ve learned to keep the message consistent across the channels even if we have to use different language." (The Electoral Commission is reviewing Brexit Party funding.)

The question is: is this genuine consumer engagement as most brands would understand it? Even though the faithful can respond to surveys and apply to become a candidate on the Brexit Party website, Murphy is unconvinced: "You get the impression of a grassroots, populist party when, in reality, the approach is very much top down." During the European election campaign, many posts were scare stories, such as "Save democracy", aimed at older voters. Yet they were delivered in a sophisticated way – data is mined and the most receptive audiences targeted. Like Farage himself, the messages were effectively succinct: the party’s average Facebook message was 19 words long, compared with 71 for Change UK.

The Brexit Party won the Facebook and Twitter war during the European election campaign. Despite producing only 13% of the party political content on these platforms, it accounted for 51% of all shares. It was helped by dozens of sites that digital agency 89up believed were inauthentic, generating hundreds of messages on one subject, Brexit, every day. Yet, given that the party spent less than a 10th of what the Remain parties did online, according to 89up, it’s hard to dispute its effectiveness.

So what happens if Brexit comes to pass in a way that Farage generally approves of? It’s an intriguing question because there is a paradox about his success. As Sinclair says: "People buy his message but they don’t buy him." To be fair, as Thompson says, his seven failed attempts to become an MP say more about the UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system than Farage’s popularity but there is also the fact "his style mobilises his opponents", she says.

In Thompson’s view, a well-managed departure from the UK could turn the Brexit Party, as high as it is riding in the polls now, into a one-election wonder. That thought might have occurred to Farage, explaining his recent, risky attempt to broaden the party’s policies. Yet he does not come across as a politician whose every move is calculated to give him the keys to 10 Downing Street. "I don’t think he’s likely to become prime minister, I’m not even sure he wants to," Murphy says. "He may be content to think he has been one of the few people to have changed the course of British history."

Meeting Farage, one senses that part of him would love to spend his time fishing at sea, reading military biographies, watching cricket and sinking a pint or two. And yet he also, as his conversation makes clear, loves politics. Asked which – if any – British politicians have inspired him, he gives a long, thoughtful and surprising answer. "I like leaders, people who do something," he says. "Thatcher achieved something. So did Kinnock, although I don’t like him, he was very brave in taking on the really horrible left of the Labour Party – the kind of people who are running it now – and making it electable again. And Blair. He told you what he was going to do and did it. I thought most of what he did was disastrous but he did it.

"And I’ve always liked Tony Benn and Enoch Powell, two great intellects who said what they believed even though it damaged their careers. Ken Clarke – if he hadn’t been so pro-European he could have been prime minister. I like people who stand for something other than just getting the top job."

After such reflections, it is strange to watch Farage on his LBC show, revelling in the controversy Widdecombe generated with her speech comparing the UK’s membership of the EU to slavery in America. The analogy was crass, historically illiterate and absurd. Farage didn’t endorse her speech, but didn’t appear to take the outrage seriously either. The risk for him as a politician is that he becomes trapped in his own bubble – an alt-right/media industrial complex where legitimate criticisms are dismissed as the posturings of a politically correct metropolitan elite.

Delaney is convinced that a successful Brexit will not be the last we hear of Farage: "Look at what happened after the referendum. With the Brexit job apparently done, it wasn’t clear what he should do next. And then a few months later, he has his photograph taken outside a lift at Trump Tower with Donald Trump. I’m convinced he was angling to be the UK ambassador. I don’t know if he ever expected to get it but I believe that was the point of the trip. He can’t stand to be out of the limelight."

In that respect, appearing five times a week on LBC is a useful platform and so are the speeches Farage gives regularly to the elite in London. "I get up there, tell ’em what I think, get one clap and know I’ve ruined their evening. I love it!" he says. Whatever lies ahead for Farage, he will have done the British ad industry a favour if he teaches it that not everyone thinks like a Shoreditch hipster.

The Five Star playbook

In January 2015, Nigel Farage flew to Milan to discover how former comedian Beppe Grillo and tech-savvy political strategist Gianroberto Casaleggio had turned self-styled political start-up the Five Star Movement into Italy’s largest political party.

"I learned a lot from Five Star," Farage tells 北京赛车pk10. "Beppe had the fame, the humour, the Italianness, if I can put it like that, and Gianroberto was a visionary genius. They used the internet to build up a grassroots movement. I was impressed by their energy and the commitment of their supporters, who were willing to pay €25-30 a year to participate in the movement."

Using digital technology, Grillo and Casaleggio shattered the mould of Italian politics. In the 2018 general election, nine years after the movement was founded, it won a third of the votes. There is still no party quite like it in Italy. "Five Star is literally a party in the cloud," Marco Morosini, Grillo’s ghostwriter and mentor, noted in La Repubblica. "No address, telephone, conferences, meetings. Only digital rituals – its cathedral is the Rousseau platform, Five Star’s operating system."

Five Star was the first "techno-populist" movement to shake Europe’s established political order but how authentic are its claims of digital democracy? Urged to "Get connected", supporters go online to make donations, vote in referendums and propose laws. Although referendum results are often publicised, it’s hard to say whether these opinions actually shape policy.

For many years, Grillo’s blog (written by his lawyers) spelled out the party line, denigrated "traitors", expelled "infiltrators" and drove fundraising.

Yet Five Star, like Farage’s Brexit Party, is registered as a private company, not a political party. Until his death from brain cancer in April 2016, the movement’s éminence grise was Casaleggio, a shy, cyber-utopian internet consultant whose company Casaleggio Associati runs the Rousseau operating system. Daniela Aiuto, a disgruntled former Five Star member, alleged: "In the movement, politicians are at the service of the communication, which was usually done by the Casaleggios or people chosen by them. These people became the managers of our existence."

Italian newspapers revealed that candidates were asked to sign a contract pledging to resign from office if found wanting by Five Star, to toe the party line and to pay a fine if found to have damaged the movement’s image.

The micro-management of Five Star by Grillo and Davide Casaleggio, son of Gianroberto, may even extend to e-voting. Italy’s privacy regulator recently concluded that it was impossible to guarantee that votes on the Rousseau platform were not being manipulated from within.

Five Star’s policies matter less than its elevator pitch to the electorate – that a corrupt, hitherto untouchable and self-serving political elite has betrayed the Italian people. On 8 September 2008, Grillo staged Fuck You Day, an unofficial national holiday celebrated by two million Italians in support of a law to prevent convicted criminals serving in political positions. The beauty of this pitch is that it is easy to remember, impervious to rational argument and, as long as there are corrupt politicians in the world, it remains resonant and relevant. "Take back control" is as just as simple, emotive and durable.

The mainstream media are, in the eyes of Five Star’s leaders and adherents, the elite’s accomplices or dupes. Vitriolic attacks on "impure" journalists (an inspiration for Farage’s fusillades against the metropolitan media) are designed to strengthen the movement’s control of online information. Five Star’s denigration of such established media brands as L’Espresso is driven by ideological discord and a battle for market share.

Italy’s online information war is fiercely contested. Born on a blog, Five Star is now the party of Facebook. A recent video interview with the movement’s Luigi Di Maio, Italy’s deputy prime minister, was distributed to 12 million Facebook followers and attracted seven million views within 12 hours.

The dark side of "Get connected" is the plethora of sites, pages and blogs that, though not officially managed by Five Star, provide an echo chamber. Scurrilous accusations against opponents are made and withdrawn. Prejudices are aired then disowned. Sites are renamed to "recycle" followers.

For all its digital smarts and dark arts, Five Star is losing momentum. Running under the anodyne slogan "Continue to change" – not a patch on the Brexit Party’s "Change politics for good" – it won only 17% of the vote at the recent European elections, almost half its share at the last general election. The death of Gianroberto Casaleggio was a setback. Grillo’s decision to hand over the leadership, but not the party, to Di Maio may have confused some supporters and alienated others. Yet Five Star remains an inspiring and relevant model for Farage and other political start-ups.

Farage’s once (and future?) ally Arron Banks has said: "The Brexit Party is a carbon copy of the Five Star movement. What Five Star has done – and what the Brexit Party is doing – is to have a highly controlled, central structure, almost like a dictatorship." Farage says he is no dictator. His new party will, he promises, "be the most open political party you’ve ever seen in Britain". Yet Grillo and Casaleggio may be better role models for him than Donald Trump, who had to seize control of an existing party. To shake up Italian politics, Grillo and Casaleggio, like Farage’s hero Frank Sinatra, did it their way.

A tick in the box for brand Brexit? Vote here

The Brexit Party is short-circuiting our brains!" That was how PR expert Mark Borkowski felt when he saw the logo for Nigel Farage’s latest creation. "It is a piece of symbolic and persuasive genius." When waved on a sign, he notes, it elicits the Union Flag arrows from the opening credits of Dad’s Army, which, according to Farage’s former wife Kirsten, is one of the Brexit Party leader’s favourite TV shows. The reference is a perfect "subliminal tick" for the target audience: during the European election campaign, Brexit Party Facebook ads were aimed at men over the age of 45.

The Brexit Party is short-circuiting our brains!" That was how PR expert Mark Borkowski felt when he saw the logo for Nigel Farage’s latest creation. "It is a piece of symbolic and persuasive genius." When waved on a sign, he notes, it elicits the Union Flag arrows from the opening credits of Dad’s Army, which, according to Farage’s former wife Kirsten, is one of the Brexit Party leader’s favourite TV shows. The reference is a perfect "subliminal tick" for the target audience: during the European election campaign, Brexit Party Facebook ads were aimed at men over the age of 45.

The party logo, Borkowski says, is even more effective on a ballot paper: "More than simply enjoying the implicit momentum of a symmetrical arrow, the subtle unexplained divot to the left of the arrow creates a desire in the voter to restore symmetry, by committing pencil to the blank box." One indignant Remainer complained to the Electoral Commission that the ballot papers gave the Brexit Party an "unfair advantage" which, no doubt, was the whole point of the logo’s design.

Designer Ben Terrett, no admirer of Brexit, posted about the logo on Instagram: "That’s going to get a lot of Xs. A helluva lot of Xs. They are a single issue, probably single election, party and that is a very clever piece of graphic design."

According to Helen Thompson, professor of political economy at Cambridge University, the logo is proof the Brexit Party is more formidable than the UK Independence Party. "The social media and video operation is much slicker than it was with UKIP – which never seemed to have a brand beyond Farage or just looking backwards. UKIP was also poor organisationally, including in the way it managed data."

Steven Edginton, a 19-year-old "Brextremist" – in the words of Alastair Campbell – has run the Brexit Party’s new, improved social media and marketing operation.

With its name and garish purple and yellow colours, UKIP always felt like a fringe party, no matter how many votes it won in the European elections. With its simple name, clever logo and subdued aqua-and-white colour scheme, however, the Brexit Party feels like a subtle step towards the establishment Farage has made a career railing against.

This is apparent on the party’s efficient, content-light website, which is enigmatically described on the home page as being "promoted by Toby Vintcent on behalf of the Brexit Party". A former officer in the Queen’s Royal Lancers (one critic says he’s "so posh he looks down on earls"), Vintcent tried unsuccessfully to help Jeffrey Archer become Mayor of London in 1999, retired from his post as marketing director at merchant bank SG Warburg when he was 42, became a thriller writer and now hands out Brexit Party leaflets.

The leaflets look more authentic than the party’s latest brand extension, The Brexiteer newspaper. Much like Farage himself, the paper possesses a certain politically incorrect wit – the front page promises "Page 3 Ann Widdecombe" and boasts that it is "Free for democrats!" – but the faux tabloid design lacks verve and, bizarrely, makes no use of the party’s logo on its front page.

The Brexit Party’s greatest branding triumph, author and broadcaster Sam Delaney believes, is its name: "If you are all about wanting Brexit, calling yourself the Brexit Party is genius." It’s not clear whose idea it was. Financial trader and hotelier Catherine Blaiklock registered the company under that name at Companies House on 23 November 2018. Her brief reign as party leader ended after her anti-Islam tweets were unearthed, but she maintains she always wanted Farage – who called her posts "horrible and intolerant" – to run it so he may have influenced the choice.

The not so subtle implication of the name is that Farage and his 100,000-plus followers "own" Brexit. And they – not Boris Johnson or Jeremy Hunt – will be the arbiters of whether it is done properly. If it proves to be another instance of "lions led by donkeys" – a favourite line of Farage’s, previously used to damn incompetent British generals during World War I – Thompson says: "The Brexit Party will become an existential threat to the Conservative Party." And, quite possibly, to the entire British political system.

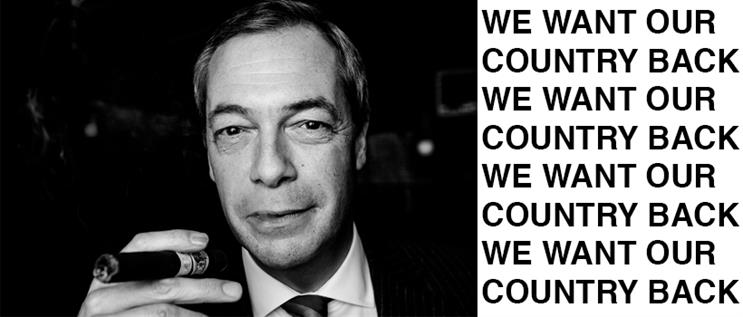

Nigel Farage photo credit: Charlie Clift

Key lessons

- Remember that emotions speak louder than reason.

- Find a simple message – as succinct as possible – and repeat it consistently.

- You can’t please everyone all the time. Find the people who are the most important to you and delight them.

- Find a way of making your brand distinctive, with assets you can own, and sweat the details.

- Don’t kid yourself that you are the target audience.

- Be bold. Not offending anyone is not the cardinal virtue of advertising.

- Be yourself. Consumers know if they’re being patronised – by politicians or brands.