A gaggle of teenagers giggle as they stroll through an interactive art exhibition on a lazy Sunday morning (they may not be in church, but still seek spiritual enrichment).

Young people now have a deep understanding of the need to switch off occasionally

A young tech-artist has created a montage of advertising relics from the previous century and fused them with augmented reality. As they walk through, the group is incredulous that people "back then" believed what companies told them, simply because a stick-thin pseudo-celebrity was plastered on a colourful, expensively shot poster or TV ad.

The idea is as surreal as the George Clooney-fronted Martini party ad they have just walked into, which suggested that if you drank Martini you too could be cool and beautiful. Just as they can’t imagine a world where the internet isn’t seamlessly integrated into everything, neither can they imagine living in a society where they’re told what to do by a company, or are nannied by the state.

From both companies and the government, they want factual information, from which they’ll decide what to do next. Communications from companies have become more like public-service broadcasts, which tell them exactly how a brand is contributing positively to the world, underpinned by hard, third-party data.

In this postcapitalist era, it’s not about looking cool. It’s about ‘doing’ cool, and that means facilitating meaningful, useful and life-enhancing things. As the teens meander out of the exhibition they peruse the shops. One girl picks up a garment but, before trying it on, checks her ‘brand-tracker’.

The point of life is not to earn a shedload of money and screw everyone else; it’s about leaving a legacy they’re proud of

Turns out this one gets a green light on price comparison, ratings by friends, match with existing wardrobe and ethical commentary, but triggers an amber light for supply chain and red for ethical sourcing and environmental re-use. She puts it back, even though she is strapped for cash and it’s cheaper than alternative options.

As she does so, she registers this boycott online, for the world to see. After all, despite her financial hardship, she doesn’t see herself as a powerless service-‘user’; she thinks of herself as a powerful service-‘chooser’. One of the teens’ wristband-beepers goes off, signalling that the air quality has reached a less than optimal level for him. It suggests he heads to a nearby park, where the air is cleaner and some of his friends are already, as well as recommending that he drink some water.

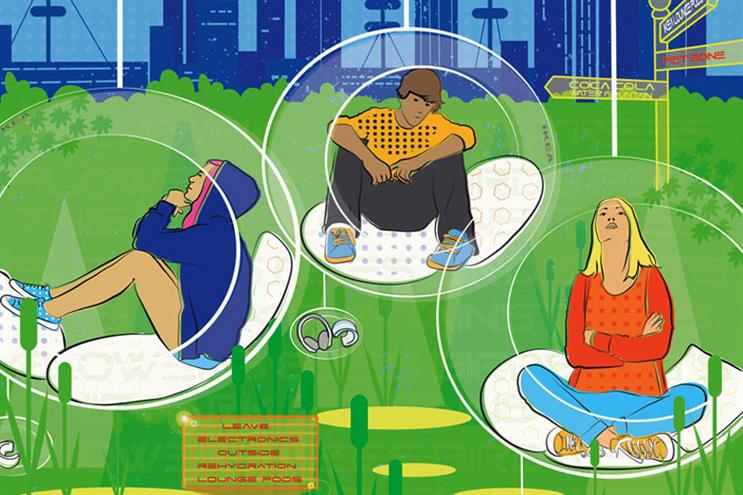

A couple of members of the group had already picked up on these environmental conditions, feeling the effect on their bodies (teens today are much more in tune with their surroundings and, for those who aren’t, there are a multitude of bimetallic apps). Being a sunny day, the park is teeming with young people, many of whom are lounging on the no-tech shaded pods, their devices safely stowed underneath, provided courtesy of a leading furniture brand.

Personal ethics

Young people now have a deep understanding of the need to switch off occasionally (they’ve seen the detrimental effect of not doing so on previous generations). Besides, they need all their energy for the week ahead – those considered a ‘success’ in this new paradigm are working in jobs that require passion and a connection to the wider world, related to something they feel strongly about. For this next generation, the point of life is not to earn a shedload of money and screw everyone else; it’s about leaving a legacy they’re proud of.

Building a better framework for living This vision of what a postcapitalist teenager could look like is based largely on the predictions of two experts who have spent a huge amount of time considering potential futures. One is Eve Poole, associate at Ashridge Business School and author of Capitalism’s Toxic Assumptions. The other is Tracey Follows, Marketing’s resident futurist and founder of the futures company AnyDayNow.

She has just published ‘The Future of Brands in a Post-Human World’, a report that examines various possibilities for the future of brands. So, how possible is this imagined future? "Ninety per cent possible," says Poole about the last chapter of her book, which paints a similar picture of what organisations at the forefront of this "revolution" could look like.

"One hundred per cent of the scenarios are already happening, just not all in one organisation yet." The trend that is driving change most is the fact that people are rediscovering their "sense of personal ethics", she adds. "We’ve been supine – so sleepy, just expecting the ‘grown-ups’ to sort us out. But people are rediscovering their moral agency, and there are changing undercurrents around democratic engagement. You only have to look at the Scottish independence vote to see that.

They use social media to validate their self-worth. They will react. They’ll be a lot more sensitised and sensitive, and more social

The ‘Big Society’ taught us something quite important about inter-relating and communitarianism, which is coming back strongly in the current narrative around Jeremy Corbyn."

Poole sees this particularly in the younger generations. Because ‘a job for life’ is a thing of the past, there’s far less fear of speaking out and questioning corporate behaviour.

Follows, who has coined the term "chooser" rather than "user", believes that the future youth will be starkly different from the current millennials. In fact, if the economic model "breaks", she believes it’s much more likely that Generation Z will break it – or, to be precise, the system will break them first, before they rediscover their strength and build a different, better framework for living."The young people I meet are much more concerned with ‘virtue ethics’," she says.

"You can see this in companies, when it comes to mutuality, for example. The old guard don’t believe in it; the youngsters totally get it. We’re at an interesting tipping point. Especially as, soon, [these] oldies will retire to the golf course."

The ‘giving’ generation

As Follows explains: "They’re under an enormous amount of mental stress and strain. They’ve grown up with the internet. They’re tested from a young age. They use social media to validate their self-worth. They will react. They’ll be a lot more sensitised and sensitive, and more social.

Whereas millennials have been ‘takers’, concerned with things like monetising their personalities online, Generation Z is going to be quite a ‘giving’ generation. They’ll come out of the other side of this stress and strain and be much more concerned about health and wellbeing.

Every marketer and his dog is spouting the virtues of having a purpose and creating a meaningful brand

They will have had enough of the way things were because it’s not a way to live."

She adds: "They might opt out completely. They’ll certainly be more in tune with their physical environment. This is not so much about us being at the end of capitalism, as at the end of a technological revolution.

I would call it ‘postconsumerism’, or some aspect of that." Brand reinvention Whether you call it postconsumerism, postcapitalism or post-human, it all means huge, inevitable change for brands, which marketers need to be planning for now, thinking more long-term than they ever have before.

One of the biggest changes relates to the idea of corporate purpose. Yes, every marketer and his dog is spouting the virtues of "having a purpose" and creating a "meaningful" brand. But there are still too many disconnections in too many brand stories for them to be authentic and credible.

Take Coke, for instance. While the Coca-Cola corporation undoubtedly does laudable social good and has several healthier options in its vast portfolio, these activities are not its lifeblood; its core business and main source of profit is its fizzy drinks business, which is widely viewed as contributing to the global obesity epidemic and adversely affecting people’s lives.

Never was this uncomfortable truth more starkly captured than in celebrity chef Jamie Oliver’s recent Channel 4 documentary Sugar Rush, which featured a Mexican baby switching from the breast to a huge Coke bottle, while the cash-strapped family partook in a religious ritual using the fizzy drink instead of water. In a ‘post-’ world, "this is not going to be acceptable, it can’t be", says Poole.

Death by boycott

It can’t be about suing everyone that doesn’t agree with you

Your backstory is your story. This was a point Unilever chief marketing officer Keith Weed stressed at the Cannes Festival of Creativity earlier this year, when he talked about the need for corporate purpose to be "genuine" and not about "doing a bit of good over here because you’re doing bad over there, it needs to be mainstream".

This will mean reinvention for many brands, and those that can’t make the necessary changes will endure death by boycott.

A brand such as Coke will need every drop of creative juice it can muster, as big-picture thinking will be its lifeline. "Brands must be brave. They may have to take their core products and turn them on their head, like BP tried to do with ‘Beyond petroleum’," says Poole.

"Wouldn’t it be amazing, for example, if Coke could be all about refreshment, providing access to a tap for everyone, even if it was also fitted with a Coke button? If it could enable people all over the world to make informed, healthy choices about consumption, even if that meant Coke was drunk less frequently and more as a treat?

One thing is for sure, it can’t be about suing everyone that doesn’t agree with you."

The confidence to be quiet As strategy director for innovation consultancy Sense Worldwide, which specialises in helping companies such as Nike and PepsiCo make breakthrough changes, Brian Millar has a few ideas about where brand reinvention could start.

Brands no longer play such an important role as a stamp of product quality – third-party reviews have taken over that mantle – which means the savvy brands in future will have to find the confidence to be quiet and humble.

"Look at a brand like Muji for inspiration," says Millar. "It is very quiet about its branding, but is appreciated because of its great design and the way it sources materials. It also has an authentic story, based on Japanese heritage and aesthetic. Visa is another great example of a humble brand; it enables, happy to hang back, concierge-like. Marketers need to switch from focusing on value propositions to creating value by making things people really want, rather than making stuff they then have to get rid of, because it’s not the right stuff."

In this model, marketing becomes the product experience itself, coupled with what people say about it; not the interruptive, ego-driven ads of old, which tell people what to think of a brand.

As Millar says, in this reality, the marketing department starts to look "increasingly antiquated".

Marketing as a public service

Will this premise (along with "The robots are coming!") turn marketers everywhere into a tailspin, as they fear for their jobs and purpose?

No. The top marketers we spoke to were decidedly up for the challenge. When asked whether he is feeling optimistic about it, Chris Clark, group head of marketing at HSBC, answers with a resounding "Absolutely. Hugely." He adds that the discussion of postcapitalism comes up frequently among his marketing team.

He agrees brands will have to learn to step back more, but doesn’t find that prospect daunting: "I find it really reassuring. It relies on companies having to wake up to the idea that, if you promise something or if you propound a point of view, and your reality is at odds with that, your business will be found out.

It’s not about [the] sloganeering marketing that used to survive in the 80s and 90s. As a marketer, it’s about saying to yourself: ‘OK, if that’s what we say, then what are we doing in terms of products and services to show that’s the case?’ If you can’t say ‘that feels fair and decent and good’, your brand will get it in the neck."

Philippa Snare, Microsoft UK’s outgoing chief marketing officer and an ISBA board member, is also enthused.

"What does postcapitalism mean to our roles? It means we start to realise everything we have been building in the last 20 years.

It means we are in the ideal place in terms of understanding the technical tools, physiological and emotional responsibility, and political and societal responsibility to lead the businesses of the future and become the most valuable public servants in a new world. We can build organisations that reinvent how to make the economy thrive; helping people do great stuff and get the most out of life, whatever their circumstances and position."

That – particularly becoming the most valuable public servants in a new world – sounds like a pretty bright, exciting potential future for marketing. It’s possible, and it’s down to you to make it a reality.