Last year, I spoke on the "Big Questions of Advertising" at the Advertising Association’s LEAD conference. One of the main themes was history’s habit of repeating itself and our perpetual inability to learn from it. We discussed cautionary tales from the 1950s, where the hubris of the pro-business boom led to ever-inflated promises of the power of advertising.

Back then, motivational research promised to use psychoanalysis and emotional techniques to home in on people’s hopes and fears with pinpoint accuracy. Subliminal advertising claimed to ramp-up popcorn sales, through micro-messages inserted into cinema reels, targeting the subconscious brain. But much of what marketing purported to do was hype and hyperbole.

James Vicary, who used his subliminal advertising study to make his business famous, was by-and-large a fraudster. The cinema where he claimed to have run his tests had never heard of him (and was too small to house the audiences he claimed in his research). Repeated attempts to replicate subliminal advertising have consistently failed.

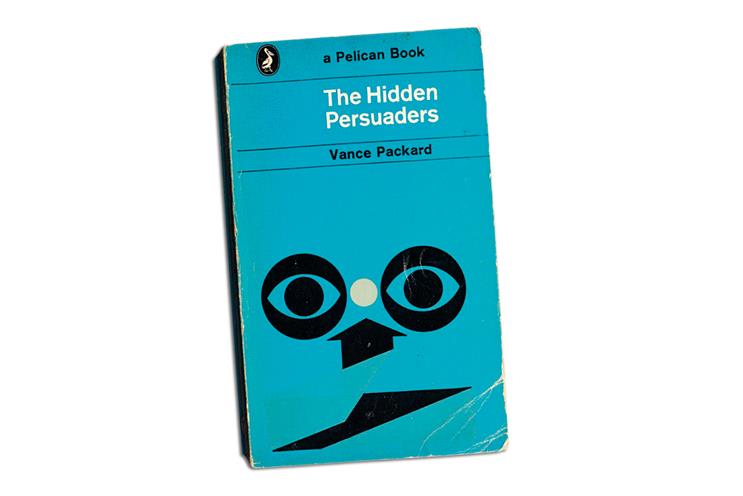

The industry had got carried away with marketing itself, and accidentally opened a Pandora’s Box of backlash. When The Hidden Persuaders was published, it was a shrill but compelling expose of marketing manipulation. Rightly or wrongly, it introduced a damning view of advertisers as secret practitioners of the dark arts outlined in the book.

Here was an opportunity for the industry to reset, to self-assess and articulate its true role in the world. Answering big ethical questions around the use of psychology, emotion, targeting or culture to change people’s feelings about brands. Acknowledging responsibility, but also highlighting positive impacts. Redefining the contract between society, media owners and advertisers. All challenges that are as relevant today as they were then.

However, rather than face into the difficult questions, the advertising industry mostly pulled down the shutters. A conspicuous exception was Rosser Reeves and his 1961 book, Reality In Advertising. It set out to defuse and debunk the accusations made by Packard, claiming advertising occurs "openly, in the bare and pitiless sunlight" and deriding much of the ‘new thinking’ around emotions or the subconscious.

"‘Freudian Complexes’ … ‘Hidden Motivations’ … ‘Psychiatric Depth Testing’ … these voodoo drums echo around a thousand conference tables every day, until the mind is confused."

Reeves provided a counter-thesis, the idea of the unique selling proposition – the USP. A highly rational model, it felt beguilingly simple yet intuitively robust. Advertisers cleaved to his explanation – there was nothing "hidden" about this persuasion.

The notes Reeves kept at the time suggest that he knew that the concept of the USP was at best a partial picture, an over-correction that didn’t truly reflect with how Reeves believed advertising worked. Much subsequent research has shown his USP model to be less than accurate and even unhelpful when describing and making advertising. Yet it is thinking that still persists today.

An attempt to "park" the difficult questions of the 50s may have benefited Reeves and his agency at the time, but it did the industry a disservice in the long run.

Today’s big questions

Today we face our own "hidden persuaders" moment. Advertisers stand accused of perniciously acquiring and deploying data to further their own nefarious ends. How we respond to this crisis could again shape the next 50 years of marketing - for better or worse. It’s a chance we should welcome, addressing ourselves to today’s big questions in ways that are more thorough and transparent, not offering ignoring them or offering glib answers that we’ll live to regret.

Ultimately, data is nothing new. Nor, of course, is it inherently untrustworthy. Data is just a tool and a tool is only as good or as bad as its user. Used well, data presents a clear win-win relationship. A win for brands and publishers, with less wastage, more insight, more accountability, and a better relationship with their target audiences. But a win for consumers, too; the oft cited edict, "if it’s free then you are the product,", contains within it an implicit contract and upside - in exchange for your data, you get free or subsidised services.

In 2013, McKinsey did a study that showed consumers in the US and Europe would be willing to pay $250bn for the value (in the form of social media, maps, search) they get for free from the internet. Problems only arise because this trade is often implicit and unclear – it’s not a fair exchange if it happens without your knowledge.

Even ignoring such utility, good data should lead to better, more engaging creative, for products consumers are more likely to want and buy. It should be part of a better advertising experience for all consumers. (That said, it’s incumbent on us to make this actually happen – using data is not a replacement for being creative. Far too often data is used to make bad advertising more effective, rather than making good advertising.)

Unfortunately, data can be used badly. Opaque and deceptive data collection. Manipulative or disingenuous use of data. We need to be clear on what is and isn’t acceptable and the misuse of data needs to be stopped. Pretty often it just involves tactless, antisocial and uncreative uses of data - as blanket targeting follows people around the internet. This devalues data and undermines the creative is should be fuelling.

Our hidden persuaders moment should be a wake-up call for the industry, but also an ice-breaker with consumers, letting us ask - what is acceptable? What data are people happy to give up to brands and publishers? What do they get in exchange?

It means moving from implicit to explicit consent to data use, along with clear ways to control it and opt-out. GDPR will continue to drive this up the agenda, but we need to genuinely understand what people want from data and advertising. Another "click here to opt-in" button does not count as healthy debate.

Facebook recently reported it makes around $20 per quarter per US and Canadian user, and around $6 per quarter per user globally. It would be interesting to see if people took them up on a $10 a month ad-free model. At least this way people would have actively chosen to continue using the free, data and advertising-powered model.

YouTube Red is a current experiment in this - letting people pay for an ad-free YouTube. Or, as we’ve seen with Spotify, a mixed economy could emerge, where some are happy to pay for ad-free, while others are comfortable with the data and advertising trade-off.

Don’t know, don’t care

The outrage over Facebook shows not only what people fear and dislike from advertising, but it also exposes the fact that people simply don’t know or much care about how advertising works. This has allowed too much bad advertising, too much misuse of data and too much wilful ignorance of the way things work (or don’t work).

Clearly, where wrong has been done it requires fixing. The wild-west days of digital are mostly behind us, but we need to continue to put regulation and safeguards in place. The systems are still too open to bad uses of data and it’s in all of our interests to fix it.

But it also gets to some fundamental questions about the impact of our industry. We are too quick to apologise or back out of a discussion about what we actually do in the world. People don’t like a lot of advertising. That should be a rallying cry for us to make better advertising, and to defend its role in society, rather than apologising or dismissing it as a necessary evil.

Advertising and data should usefully underpin an ad-funded society, culture and services. It connects people to products they want. It makes brands richer and more valuable through creativity. It creates a market and an outlet for innovation. It supports commercial TV, subsidises public travel, helps fund publishers, newspapers, search, social media, maps.

We shouldn’t be afraid of asking the difficult questions that help us do this better. To borrow the words of Rosser Reeves, we should embrace our moment in the bare and pitiless sunlight as our chance to shine.

Oliver Feldwick is head of digital strategy at The & Partnership