There was an old phrase my gran used to use about “cobblers’ children going barefoot”; meaning that people tend to be terrible at practising what they preach. It came back to me this week when I read about the Engine "auction".

As an industry, we continually and consistently tell our clients about the power of brand. We preach from the rooftops about creating intangible value and about how much commercial return will come from investing emotionally and financially in “the brand”.

We planners spend inordinate amounts of time repackaging the [Les] Binet and [Peter] Field argument about sinking 60% of the budget into emotionally resonant, brand-building comms so that consumers can have a stronger, more loyal relationship with "the brand". We drone on to the point of saturation about getting customers to buy "into" something rather than just buy "from" someone.

Yet when it comes to our own brands – as agencies – then the sort of decisions we’ve seen from holding companies in recent years are thoroughly baffling.

Agencies, but especially holding companies, have consistently acted in exactly the opposite way to the mantra they preach to their clients. A couple of years ago, Engine got rid of some of the most respected brand names in the industry and replaced them with capability descriptors under the name of the holding company. So, when it comes to the "auction" in the article, what exactly are investors being asked to pay for?

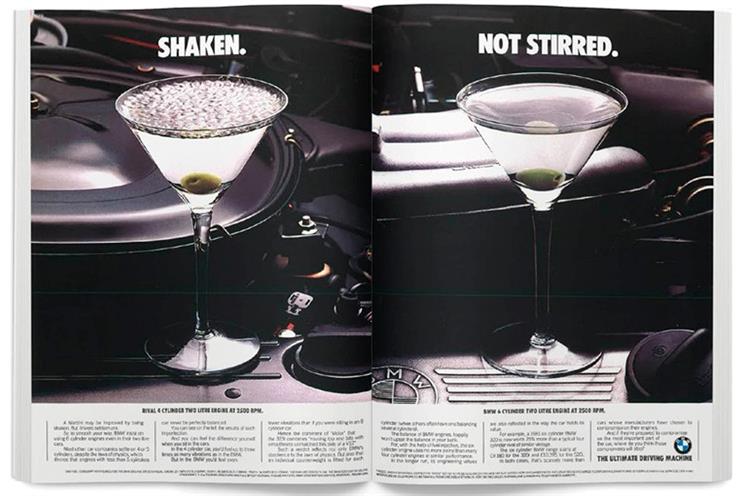

When I entered the industry in 1995, White Collins Rutherford Scott was one of the most respected and feared creative companies in the UK (see BMW ad, pictured above). Even in recent years, it had built a fabulous reputation off the back of great work for Warburtons (below) and the like.

PAA was one of those "direct shops" that all of us in the hierarchical world of ATL always respected and listened to. Then suddenly these names were dropped in favour of a descriptor of what they did for a living. A bit like Unilever suddenly deciding to rebrand Lynx and Dove as “lads’ deodorant” and “women’s soap”.

It’s not just Engine, though. This commoditisation in the name of convenience has been going on for a while. Ogilvy did a big re-org a couple of years ago to do the same exercise – merrily binning names with many decades of equity in favour of generic descriptors like "Advertising" or "PR". It seems curious to me at the time and very contradictory to the "making brands matter" mantra.

WPP paid $566m for the J Walter Thompson brand name in 1987. Then they threw away that name – which had been invested in over a century – a couple of years ago. It paid a whopping $5.7bn for the Young & Rubicam name, equity and reputation in 2000 and then pretty much casually canned it last year.

The behaviour of tossing names with decades (or centuries) of equity aside without seemingly any thought seems baffling. If we want clients to think their brands matter, why don’t we demonstrate to them that we value our own?

I suppose the argument would be made that the equity is being built in the holding company brands, but is it really? People buy into brands and brand values. It takes years; decades. I don’t really care about Reckitt but I do care about Dettol, Durex and Finish. I don’t really give two hoots about Procter & Gamble, but I do care about Pampers or Olay. Would I care as much about the those last two if they were rebranded as P&G Nappies or P&G Face Gunk?

This is what we do when we rebrand our agency brands as capabilities. We sacrifice our specialisms for convenience and efficiency. And we also dangerously commoditise our offer and make our internal agency cultures irrelevant. Basically, we become – and who’d volunteer to work for them?

I hope if/when the Engine auction comes to its conclusion, we’ll see an emergence of the various capabilities within that group as fierce, strong and successful agency brands – they’ve certainly got some talented leaders there who could run them. I think that would be a brilliant signal that specialism matters and agency brands and cultures matter, too.

People want to be proud of where they work. But it’s not a coincidence that the best and most successful agencies tend to be independent, creative ones – not anonymous "capabilities" under a big, faceless, corporate umbrella.

If the industry consistently demonstrates to its clients that it has no loyalty to its agencies, then why should we expect them to have any in return? If we show that we can toss aside our agency brands without a moment’s thought, then why do we moan when clients don’t invest in their own brand? But most importantly, if we keep showing clients that we have zero interest in our own brands, then why should we expect them to have any trust that we’ll take care of theirs?

Kev Chesters is strategy partner at Harbour.