Wendi is a workhorse. For 24 hours a day, seven days a week, she is on the go.

Wendi is a workhorse. For 24 hours a day, seven days a week, she is on the go.

Over at reception, she analyses a companywide calendar for major meetings, key visitors, project milestones, goals, and deadlines, all before diving into workstation availability.

She pings simultaneous team members to confirm attendance and assign activity zones, then moves on to the café.

Yes, Wendi knows every employee’s morning beverage preference. She gets to work brewing, using the calendar analysis she just completed as a guide to whose order comes next. Then she turns her attention to facilities.

Here, she reviews a heat map of employee disbursement to ensure that the temperature, lighting, and ambiance of each environment is set to the appropriate team’s liking. In the "quiet zone," she has turned on the soft lights overhead and queued up the musicstreaming preferences for each of the day’s occupants, unraveling headphones so that they’re ready to go.

Next, human resources needs her for candidate screening. From facilities, she switches to security, analysing anticipated internal and external movement, shifting personnel as required. Now that the logistics are (for the most part) out of the way, Wendi starts to have some real fun.

Tag-teaming meetings with her human and automated counterparts and tackling challenges, goals, and any and all data that teams will share with her, Wendi plays her most crucial role: providing assistance to the staff and collaborating on projects as needed.

Wendi is a Jane-of-all-trades—everywhere at once and completely invisible. In fact, she isn’t real. Short for workplace enhancing network distribution intelligence, Wendi is a fictionalised robot, an amalgamation envisioned by any science-fiction aficionado for the home, office, or otherwise, and aided by a humanlike, artificial-intelligence interface.

She is also a wild depiction of what many fear will be the end of the common laborer: automation. "Scarlett Johansson [in the film Her] is exactly what we won’t get," says Nick Coronges, EVP, Global CTO, R/GA. "There will be more robots in physical spaces for sure, but if you know how to use computers, and how to use software, you’re still going to be doing that, just at a higher level."

The idea of a robot takeover is not new. Robots have been working alongside us for decades, a fact known well in the manufacturing industry. But in recent years, advanced, agile robots have been taking on more human tasks and doing them faster, for longer periods of time, and nearly error-free.

No wonder people are concerned that robots will take over manual labor, and menial tasks that many humans have relied on for jobs—perhaps even eliminate some occupations entirely. Such jobs have been disappearing for some time now.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in the manufacturing sector declined by almost 6 million jobs from 2000 to 2010. While mostly attributed to off-shoring and the 2008–2009 recession, recent analysis from McKinsey & Company suggests US manufacturing will likely look a lot different because of this new generation of robots.

The analysis showed 60 percent of all occupations could see 30 percent or more of their activities automated, and today’s technologies could automate 45 percent of the tasks people are paid to complete. And yet across every industry, companies are facing an unexpected talent shortage.

It seems as if every week, another retailer announces that it will shutter its physical doors and shift to an e-commerce–only option: Sears Holdings (which owns Kmart), Macy’s, and J.C. Penney have announced 100 or more store closures in the past year.

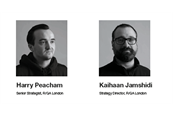

"We are in a talent arms race now," says Alex Wills, Executive Director, Content, R/GA London. "A lot of companies are realising they need to hire a new type of person that they’ve never needed at their organisations before."

Wills, who is working with manufacturing and electronics giant Siemens to define and build up its "employer brand"—which refers to a company’s reputation and its value proposition to its employees—finds it shocking how few organisations have failed to recognise this.

Now that millennials make up the majority of the US workforce and the digitisation of everything continues to proliferate, more companies are facing an internal branding problem when it comes to securing key talent. "I thought the digital revolution was going to start a long time ago," Wills says.

"Only now are senior leaders understanding the true importance of digital and the transformative effect it is having on their workforce and business. Data sources like LinkedIn and Glassdoor identify a huge amount of information and show how powerful these platforms have become. It’s forcing brands to be much more transparent than they’ve ever had to be, so their external and internal brands should ultimately be the same."

Blending an external brand with the internal culture is not necessarily a new notion. It is, however, only a recent formal strategy that some companies like Siemens have been exploring in response to the forced transparency organisations face.

Lachlan Williams, Strategy Director, R/GA London, suggests that companies can no longer afford to sit still and wait for key talent to come to them.

"With a few taps on the keyboard, job seekers can find out pretty much anything they want to know about a business or what it’s like to work there," Williams says. "Businesses have nowhere to hide. They have to actually prove that they are what they say they are."

This shift is no different from what happened to companies as social media infiltrated the marketing world. Suddenly consumers started speaking directly to brands and each other about the products they love. Today, sites like Glassdoor and LinkedIn give people a peek behind the curtain at companies, and if they don’t like what they see, there are plenty of other employers.

"The increasing competition for talent is driven by similar conditions we see creating disruption in marketing and communications," Williams explains. "New technology, choice, an overabundance of information and access to it. Much like how a brand can’t put out an amazing message about something it stands for if it doesn’t actually practice it. The same principles are now applying to employer branding and the workplace."

Competition these days is a result of massive cross-industry digital disruption, with every organisation having to reframe itself as a software company to meet consumers where they are, offering products and services on platforms familiar to its end users.

Whether a bank, a grocery store, or a manufacturer, technology is seeping through the walls and rewriting the rules of work. "Technology, globalisation, and the millennials are the three biggest drivers," says Andrew Lam-Po-Tang, Executive Director, Business Transformation, R/GA London.

"That generation’s expectations will become embedded in the workplace and in the marketplace. Things such as services-on-demand, like Uber and Airbnb, are what millennials quite rightly take for granted and start to shape their expectations when they’re consumers at market, of what they should expect from the companies serving them."

To put all of that into perspective, consider that 57 percent of millennials would change their bank relationship for a better platform solution, according to the Millennials and Wealth Management study featured in the July 2015 issue of Deloitte’s Inside magazine. This is just one industry in which today’s youth would choose new tech-based platforms over traditional institutions.

"There are all these amazing services that we take for granted on our phones that are free or nearly free," Lam-Po-Tang says. "And the services that we get as individuals are not dissimilar to some of the services that we consume as employees, yet the ones we are given at work are rubbish in comparison. Millennials really feel this pain."

Employees are people, too

The revelation that customers are people is just one step removed from the idea that employees are customers. For many organisations, being customer-centric is a given, but for others, being people-centric is harder to grasp.

"We have to design around people, not our own operational structures and limitations," says Saneel Radia, SVP, Business Transformation, R/GA. "HR specialists tend to think about employees in terms of their own responsibilities, or through discrete, mandated interactions like interviews and performance reviews. But when we reverse our perspective, focus on the employee as a person, and put the employee-employer relationship first, the value of experience-driven services becomes immediately apparent."

Radia and his team are helping clients such as Siemens navigate and design these new employee-employer relationships. "For us, an employee value proposition is absolutely necessary," says Radia. "Start to understand your employees as segments. Not in the old-school marketing way, but through their individual motivations. Why is this person here? What will keep them here? They might be looking for money, learning, or camaraderie. Each person will value those in a unique way. If we can identify those specific value propositions, we can build strategy that enables employee experience design. The idea that regulations and strict governance are the core of employee experiences is painfully outdated."

To truly understand the value proposition of various employee segments, companies must start to consider their employee journey, or employee experience. What was once thought of as a strictly onedirectional, upward climb has morphed into a flexible, unstructured relationship between employee and employer.

"The idea that the employee experience is hierarchical and ladder-based is a vestige of the past," Radia says. "Most companies are thinking more fluidly, because the work force is fluid. Skills are changing all the time. If they can get a lot of people feeling really good about their employment for a period of time vs as a stage in a life-long journey, that’s mutually beneficial. It fits a more modern mind-set of employment, and there is something very powerful about the idea that the employee will fluidly move across a lot of organisations."

Another significant outcome, he says, is the employee’s potential to boomerang—that is, to leave the company and then return at a later date. Today’s employee experience is being flipped on its head. In fact, companies are completely restructuring their human resources department so that it will be a component of the employee experience, just one piece of the puzzle that brings together all the touch points that anyone who works for or engages with their brands will experience.

The ladder, then, has evolved into a loop— and one not dissimilar from the customer journey—through which a candidate cycles through their experience with a brand from awareness and consideration, to application, to hiring and onboarding, to the technology and tools designed to promote the best work, to leadership training, and all the way through to offboarding. (See "The New Employee Experience," page 3.)

"There’s been a message change in the way we consume things and interact at work," says Amy Materka, Director, Business Transformation, R/GA London. "We’re employees, but we still have this expectation that all transactions should happen here, that things should move quickly, we should be connected. We can use multiple ways to communicate, we don’t need to wait for top-down instruction on how to think or what to buy, because that’s the old marketing world. The new world is about looking for what is good for us, and that fundamentally changes the world of work."

One of the most fundamental changes in the world of work has to do with the notion of being chained to a desk. Connectivity has unlocked an entirely new set of behaviors that enable companies—and their employees—to work in ways never before possible.

Think of the smartphone: how it has resulted in an always-on culture and the conveniences it affords to consumers who are now seeping into the workplace. Whether in the physical or digital space, companies must design more fluid and flexible work environments not only to match the habits of employees but also to foster mobility, collaboration, and open communication across entire organisations.

"It’s all about connections," says Nick Law, Vice Chairman, Global Chief Creative Officer, R/GA. "One definition of innovation is taking two different ways of thinking and combining it to make a third way of thinking," Law says. "You can only do that if you can connect those original two ways."

Gone are the days of the industrial enterprise with a 9-to-5 workplace. In its place are networked companies that run more akin to Silicon Valley. From in-person interactions to crosscontinental workflows, employees can now engage with various parts of a company without time zone restrictions or layers of hierarchy.

At R/GA, this manifests as a networked company, supported by a suite of communication- and collaborationbased products and services that can be deployed at any one of our 19 locations around the world.

"High-performing companies have incredibly strong social connections between people in the company," says Josh Bersin, Founder and Principal at the consultancy Bersin by Deloitte. Bersin has been researching how HR works for the past 15 years. He predicts that digital disruption is transforming the way we think about work and, even more so, jobs—especially those that historically require manual labor. "The idea of technology helping us do our work is not new," Bersin says.

"That’s been going on forever. But right now, there’s a flurry of technology that is reinventing what the job is. Jobs that are very transactional are going away, and jobs that are empathetic, service-oriented, and very creative are going up." The roles that require more creativity are inherently more collaborative. They’re also dependent on actual humans operating as nodes that contribute to the network rather than working in silos.

"If you try to optimise the network," Bersin says, "you want to make sure that people are connected to each other, that people feel empowered, that there’s a lot of alignment around the mission and the goals… and that people have mobility so that in a network, if one of the nodes fails, the data goes to another node."

"Messaging is the fundamental application of computing technology to the lives of human beings," said Stewart Butterfield, CEO of Slack, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal’s Senior Deputy Technology Editor Scott Thurm.

By the year 2020, there will be 5.7 billion smartphones globally, up from 1.9 billion at the end of 2016, according to GSMA Intelligence’s Mobile Economy 2017 report. These devices are creating connections all around the world, from generations of families to global businesses and their customers.

While its most sophisticated feat is cramming a computer into the pockets of billions of people, the smartphone’s greatest application is enabling this borderless communication. In today’s workplace environment, companies don’t just face disruption in the marketplace, they face it within their own walls.

IT departments must rethink how they can serve the shifting needs of employees, moving away from enterprise software and hardware to fully embracing the option to bring your own device (BYOD), and now bring your own cloud (BYOC).

"There was a time when you had staff that would basically sit inside the IT ring/fence and their job was simply security and policy," says R/GA’s Coronges. "Now IT departments recognise people are already using their own technology. What IT needs to do is create the kind of environment that effectively brings the same tools and technologies and essentially manage these services without losing control of them.

"Instead of eliminating them or creating policies against them," he continues, "we have to figure out what the people are using and have policies and infrastructure to support them."

BYOC and connecting employees across a global network have evolved from BYOD now that services such as file-sharing and storage tool Google Drive and messaging app Slack have become ubiquitous in the workplace. Launched in 2013, Slack snuck in by way of small collaborative teams, in particular the developers and other nimble creative groups working on different pieces of a larger project.

Slack’s communication platform allows users to set up a channel— be it project- or team-based—to communicate updates, share files, and request real-time feedback and approvals on different stages of work, all while giving an entire team complete visibility into the project. But in the past there have been tools like Slack’s that did not catch on as fast.

Enterprise-facing companies such as Microsoft and others have tried to create this virtual workspace, but none has been met with Slack’s rapid acceptance and adoption. As of last October, the company reported that it had 4 million daily active users.

The difference, it seems, is Slack’s ability to adapt and mimic existing habits and behaviors rather than try to create new ones.

"Now that all the digital services that we access as consumers have been advancing at such a rapid clip, whenever we go into a new company—an innovative company that thinks about the staff experience—we expect that it is also delivering services in that way," Coronges says. "The staff is expecting everything to work [as seamlessly as] Uber."

Communication as a seamless, fundamental application in the workplace is the first step for businesses that are starting to think about their employees as people first. Creating that communication beyond the immediate four physical walls is next.

Offices must be designed to empower connectivity, creating an invisible network that links a team in New York to a team in South America, Singapore, or any other corner of the world, as R/GA’s network of global offices are. At Unwork, an organisation that studies and consults on office design, CEO Philip Ross believes there should be no chance encounters in the workplace. Instead, companies can use data and design to help create them.

"What if social networks collide with the physical space and you build a realtime social network where the system introduces people to each other?" Ross says. "This idea of a collision coefficient, engineering serendipity—there are millions of app solutions emerging for this."

But connectivity isn’t only digital. Businesses should be connecting people offline, too. As the world moves away from manual labor toward jobs that require more complex cognitive skills, offices must evolve as well.

"As we head towards a much more creative, knowledge-based society, those people and their activities inside offices have to change," says Ross.

Rather than a static, siloed environment based on hierarchies, companies should design a space that enables the behaviors already taking place there.

"Forget about the software and technology that’s embedded in the space for a second," says R/GA’s Law. "Just having an open floor plan means there are no longer walls between me and the people I am working with."

Designing workplaces around the way people actually do their jobs will take more than physical and digital architecture. It requires people experts who are well-versed in the habits of consumers, and people who are able to spot behavioral patterns and design experiences that re-create those behaviors. It takes a new mentality about the world and the implications for the new ways people interact in an office.

As R/GA’s Materka puts it, "In a world where you’re making knowledge and you have to make it together and diversity helps, then you’re going to collaborate.

"That to me is this new mind-set of people who are ready to embrace new ways of doing things," she says, "because they see that it’s going to be better for humans… We’re making the world more machinelike, so we need to make our human structures more human."

Tara Moore is managing editor at FutureVision