#MeToo lifted a lid on a reality that most men had never considered. A virtual outpouring of emotional trauma, shrinking ambitions and professional humiliation that had remained culturally invisible for decades. Women’s voices were heard, often unfiltered through social media. Words were formed and stories were shared across the world describing brutal experiences of sexual assault that individuals had never even articulated to their closest family members.

Twelve months on and the backlash is already in full swing, yet the power of these female-led narratives has already driven a fault line in the traditional gender stereotypes and power structures that demand a wholesale shift in all aspects of public life, including marketing. The promise of a third wave of marketing to women rooted in equality, diversity and individuality offers brands the opportunity to better connect with half of the world.

The future of marketing to women is genderless

If the first wave of marketing to women was typified by the "pink it, shrink it" brigade (largely criticised on the basis the marketing industry was awash with products created by and marketed by men to women), its second wave afforded the promise of something different. From the rise of "femtech" to the range of products and services created by women for women, this female focus has created marketing moments that just a year ago would be almost impossible to conceive.

Take the example of Bumble, the female-founded dating app, which took out full-page ads in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal that implored: "Believe Women." The ad, published one day after Christine Blasey Ford testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee about her sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, propelled the brand into unchartered territory.

Yet far from this being the end of the story, a third wave of evolution is already in full swing – and it is one that demands brands shift beyond viewing gender as the defining factor in any given audience and embrace instead an equality of design and function. Victoria Buchanan, senior strategic researcher at The Future Laboratory, believes that we are now at a critical point – where the dominant narratives and gender stereotypes are being challenged. She explains: "Post-#MeToo, brands are already abandoning tired gendered design cues to redefine modern female identity, and embracing a bold, vibrant aesthetic to communicate this diversity." A diversity of approach that has the marketing potential to connect just as much with men as it does women.

Equal by design

In this way, the future of marketing to women is increasingly genderless. Tracey Follows, founder of Futuremade, says this evolution will become evident with a shift in focus away from "made by women for women" campaigns, products and services, and more focus on campaigns, products and services that just happen to be made by women but could be for anyone. She explains: "It is a shift that is underpinned by the individuality of the consumer."

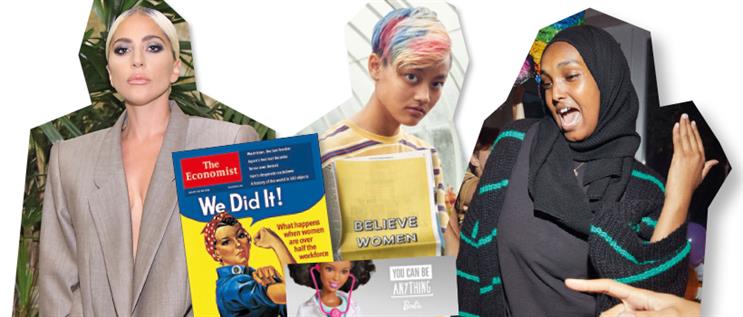

This step change in approach has been embraced by The Economist, a news brand historically built upon an authoritative masculine tone. The brand underwent a cultural reset internally and externally by imagining a world where gender equality is achieved to better propel its marketing approach toward it.

Marina Haydn, executive vice-president and managing director for circulation at the brand, says The Economist is part of this third wave: "We don’t want to be marketed in a gendered way and the problem was that women felt that we weren’t speaking to them, which is why we embraced a more inclusive, dialogue-led tone, rather than speaking from a pedestal of authority. It was important for us to see it as an opportunity. The problem is with us as a brand, we have not been connecting with 50% of the world. It was clear we were missing a business opportunity and it was important to turn the lens inwards. The question was not for us to understand why women weren’t reading The Economist, it was why weren’t we speaking to women."

Changing the narrative

Historically, so much of marketing to women has been built on the presumption that women’s primary goal is to attract the attention of men. A focus that supersedes their own comfort or self-actualisation. Yet Kit Krugman, president of Women in Innovation and chief curator at Co:Collective, says not only are these status quo narratives failing to connect, they are the death knell for many brands and businesses: "When you provide people with things they don’t relate to, they won’t simply not buy your product, they will build something that they can relate to."

Many brands that have relied on these status quo narratives are already in the midst of product and marketing pivots. Consider how Barbie, a global symbol of unrealistic beauty ideals, is now being marketed as a force for change. Sairah Ashman, global CEO of Wolff Olins, says its newest ad, which addresses what it calls "the dream gap", reflects how the brand does not want to represent the "old world order" but instead taps into women’s anger, as young girls voice some saddening facts – such as that girls are three times less likely to be given a science-related toy than boys. "Consumers want brands to be pushing for change in gender equality," she adds.

A collision course

It is not only Barbie who is in line for a long-overdue makeover. From the rise of androgynous clothing brands such as Asos’ Collusion line to Lady Gaga’s decision to wear a men’s Marc Jacobs suit on the red carpet, traditional gender aesthetics are on a collision course. Consider the anger that met the launch of Hedi Slimane’s first collection for Celine at Paris Fashion Week, described by one fan as "a big fuck you to women".

The collection’s focus on skin-tight dresses and mini skirts marked a step change for a fashion brand that has long embodied the female gaze under British designer Phoebe Philo. GQ’s contributing editor Lou Stoppard took to Instagram to explain: "This idea that his singular vision is so essential, societal, that it should be projected again and again is so offensive especially under the name of a brand that was known for a sense of dialogue with the women who bought it."

In fashion, specifically, the sort of strict gender norms that contribute to the power imbalance that creates #MeToo are crumbling

Slimane fell short, just like many brands and designers before him, because that sense of dialogue or empathy for the audience he was designing for was palpably absent. He was creating for an audience that does not exist.

Follows says that we are in the throws of a rebalancing of power between male and female genders. Traditional identity marketers like gender descriptions are collapsing in a way that is making the binary nature of gender, as traditionally used, less and less relevant to the future. She explains: "The reasons for this are complex but at their most basic, much is bound up on our notions of individual identity and how we can use identity to create cultural capital for ourselves in a world where cultural status, rather than financial status, is becoming more important." In essence, in an age in which consumers can freely create and curate their own identities on social media channels, gender is just the first of many demographic descriptors that are poised to become less relevant to marketers.

Cultural capital

Yet, while the promise of brave new genderless futures are important to brands, it is equally important to note that to date much of women’s cultural capital has been derived from their singular experience as women. Notably the collective fuel of women’s anger has been a huge force for rejecting and challenging the traditional tropes of marketing to women. A collective fuck you encapsulated by actor Jameela Jamil’s response to Kim Kardashian-West advertising an appetite-suppressant lollipop to her 111 million Instagram followers: "No. Fuck off. No. You terrible and toxic influence on young girls."

Rachel Pashley, global planning director at J Walter Thompson London and head of Female Tribes Consulting, believes brands need to pay attention to this anger and how they serve and represent women. Pointing to the research that revealed STEM jobs advertised on Facebook were more likely to be served up to men, gender bias is built into media algorithms, a state of play that impacts both the professional and the personal.

"As a woman I’m constantly served up weight-loss supplements, yet I have never actively sought these out. Yet an algorithm somewhere has decided that as I’m a woman, I’m in the market for them: that makes me angry. It points to just how systemic gender bias is and how much we have yet to do to challenge the world in which we live," Pashley adds.

A sense of dialogue

The global community of women connected by the #MeToo movement has helped to shift imaginations away from these stereotypical representations of female sexuality. Dr Karen Correia da Silva, senior social scientist at Canvas8, explains: "In fashion, specifically, the sort of strict gender norms that contribute to the power imbalance that creates #MeToo are crumbling."

The Modist, the world’s biggest luxury fashion destination dedicated to modest dressing, was well ahead of this curve when it launched two-and-a-half years ago with a laser focus on the diversity of women’s wants and needs. Lisa Bridgett, chief operating officer at the brand, says that in the past the fashion industry has been rooted in dictating to women but today it is about adapting to their needs. "The creative arts should be the heralder of what is open in the world, but when we look back over the past 10 years, fashion was very much driven by a male lens," she says.

The perils of ignoring half the world

This self-actualisation presents a turning point in how brands connect with women as individuals. From fashion to finance and publishing, no sector is immune from this shift – and taking account of the cultural temperature of the time has never been more vital to forging meaningful connections. Lily Fletcher, strategy director at Accept and Proceed, says the #MeToo movement combined with the growing focus on fake news is having a huge impact: "Now, more than ever, if a brand is doing something without conviction or following a trend, it feels inauthentic. Brands need to have a greater emotional awareness of consumers as individuals."

It is a change that demands marketers as individuals, irrespective of gender, remain committed to seeing the world through a lens other than their own – to embrace the uncomfortable. In Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, writer and activist Soraya Chemaly describes women’s anger as an "act of radical imagination". Should it be viewed as equally radical to imagine a world in which the wants, needs, hopes and fears of each consumer are treated equally?