Last week, The Sackler Trust announced that it was pausing all donations to arts organisations in the UK. The decision came after leading galleries, including the Tate, National Portrait Gallery and New York's Guggenheim, said they would no longer accept grants from the organisation.

These galleries acted because of the controversy surrounding Purdue Pharma, a company owned by the Sackler family that makes OxyContin, which has been accused of fuelling the US opioid crisis. Artist Nan Goldin’s protest group Pain (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) had organised demonstrations against Sackler funding at the Guggenheim and Metropolitan Museum of Art, threatening more protests at the Tate ahead of her show there in April.

The announcement from The Sackler Trust led to stark warnings from some in the arts world. Sir Christopher Frayling, a former head of Arts Council England, said it was a "sad day for the arts" and warned against organisations becoming "too squeamish" about where their sponsorship money comes from.

He may not have meant it this way, but it all sounded a bit "don’t ask, don’t tell". We should be having an honest conversation about who pays for art and why they do it.

Brands that want to be involved in sponsoring, commissioning and financing creative work need to be open to this conversation. There are two interrelated questions that any such brand should be able to answer: why are you doing this? And what kind of work are you supporting?

Let’s deal with the second question first. When I first joined WeTransfer to oversee its content team, the rule was "no sex, no politics, no religion". I pointed out, only half-jokingly, that this ruled out all good art.

I could see why the rule existed. WeTransfer is a file-sending service. People don’t come to us to be challenged or provoked; they come to send big files. But we’re also a company that is publicly committed to creativity. It felt like we were trying to have our cake and eat it; to commit to the creative world but on our own terms – safe, sanitised and sure not to ruffle any feathers (ie put off any customers).

For a few months, I was happy to play along. I had a good job and we got to make good stuff. We turned down controversial projects and steered others on to safer ground.

I was wrong. I was a coward. And I’m lucky that I was surrounded by people who pushed me out of this cozy complacency.

I came to realise that it wasn’t just that we could be telling more challenging, divisive stories – we should be telling more challenging, divisive stories.

It’s a rough time for online media. Most publishers need eyeballs, and this encourages them to tell stories that attract the most people possible. That can often mean that messy, complicated and difficult is out, while safe, soft and simple is in.

And publishers need advertisers, many of whom don’t want to wade into social, cultural or political conflicts. They don’t want their ads next to anything too harsh or confrontational. It was depressing, but not wholly surprising, to read that

If a brand like WeTransfer is going to bother commissioning and curating creative stories, we should take advantage of the position we enjoy and push ourselves to showcase work that might be considered controversial.

So that’s what we did. First, it wasn’t commercial suicide. 2018 – the year we gave more space than ever to these sorts of projects on and on the WeTransfer.com backgrounds or wallpapers – was also our best-ever year for advertising. Clearly, brands weren’t put off by appearing next to these sorts of stories; we’d like to think that some of them even shared our belief in their importance.

More importantly, we saw that some of our most popular pieces were stories that are hard to tell, hard to listen to and hard to watch – from to

We are determined to make work that means something, and we know that will often mean trusting the creatives we commission and not worrying too much about the commercial consequences.

Take Tobias Nathan’s film . Initially, he went to Brazil to find out how and why women (especially queer women and women of colour) were taking over the country’s sacred samba circles.

The women he spoke to took the film in a different direction. They wanted to talk about politics and violence and the way women are treated in scoiety in Brazil, where the election of a new president has emboldened and encouraged some of the country’s worst instincts (sound familiar?).

The women Nathan met are scared and angry and defiant. We not only hear their stories, we’re also shown the depressing facts about violence against women in Brazil. And, in one sequence, we see real news footage including a dead woman lying on the street and another woman, Tatiane Spitzner, being beaten by her husband in an elevator. Hours after that CCTV footage was captured, she was dead, strangled and thrown from a fourth-floor balcony.

It’s really upsetting. It’s really difficult to watch. But that doesn’t mean we should look away. This context is why this story matters and why this film is about much more than samba music.

Maybe in the creative world, we’ve become too comfortable. Internet culture is designed to reinforce what we already know, think and feel. Algorithms are evolving ever-cleverer ways to feed us things that feel familiar, that pander to the lowest common denominator. When was the last time you were really challenged? Confronted? Provoked?

And brands aren’t helping by wading into the content business in a way that too often pumps out more of the same. What a missed opportunity, when brands have the time and space and money to commit to making things that feel different.

But that will mean pissing people off. Writer Marlon James recently appeared on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs. He picked Nirvana as one of his choices, remembering the feeling when he first read the liner notes for Incesticide in 1992.

In those notes, the band wrote: "If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different colour, or women, please do this one favour for us – leave us the fuck alone! Don't come to our shows and don't buy our records."

Speaking nearly 30 years later, James was still moved by the impact the words had on him: "It was the first time I felt like somebody got my back."

And herein lies the answer to the first question brands need to be able to answer – why are you doing this? Because people remember those who make a stand and because building an emotional connection with people – not customers – is hugely worthwhile.

You may lose some customers but, like Nirvana, I think we should be OK with that. If we want to get involved in telling stories that matter, then we need to be honest about what this means.

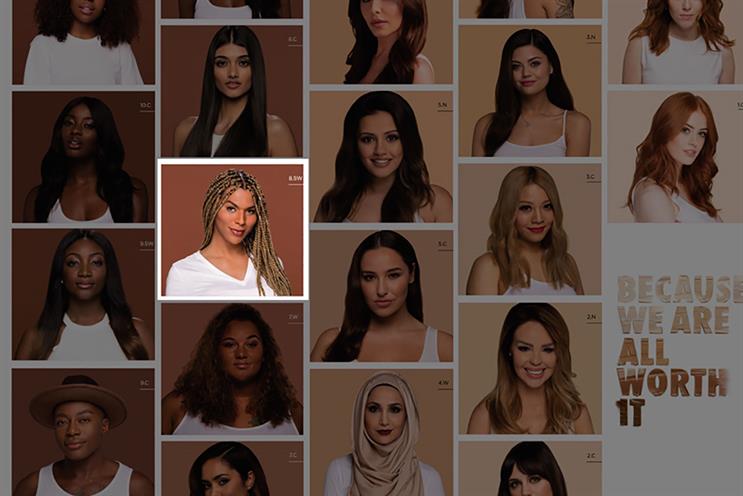

L’Oréal wasn’t honest. In 2017, the French beauty brand unveiled black transgender model Munroe Bergdorf as one of the faces of its "#AllWorthIt" campaign. A few days later, after Bergdorf wrote on Facebook that white people’s "entire existence is drenched in racism," she was fired.

It was the perfect example of a brand that wanted to be part of the diversity conversation, until that conversation showed any hard edges or raised any difficult questions. L'Oréal wanted brand-friendly activism, which isn’t the same as activism.

As Aminatou Sow on the Call Your Girlfriend podcast put it: "Going into an arena of activism is to go to a place of conflicts. You are going to the mat every single time."

The fight to build a better world won’t always be nice and neat and photogenic. We should be ready to embrace that.

Rob Alderson is editor-in-chief and vice-president of content at WeTransfer