Few industries have changed as dramatically as the commuter press market over the past decade. The launch of free title Metro - the UK's first urban national newspaper - in 1999 prompted a flood of copycats, and commuters now face a deluge of free titles offering everything from business news to celebrity gossip.

When ShortList Media announced this month's launch of Stylist - ShortList's sister magazine aimed at the female commuter - in July, it seemed as though the free market knew no bounds, even in the throes of a grim recession. In August, News International announced the closure of thelondonpaper, and the free bubble was in danger of bursting, but then the London Evening Standard breathed new life into the model by becoming a free paper from this week.

Looking ahead to what the industry hopes will be the brighter days of 2010, will free titles dominate the commuter press market, or is the demise of thelondonpaper a harbinger of doom for that particular high-risk experiment? And what about news delivered electronically - will print newspapers vanish from the daily commute as consumers start to scan the day's headlines on their mobiles?

Back in 1999, the launch of Metro by Associated Newspapers was a gamble. Its business model was untested in this country and many predicted a newspaper funded solely by ad revenue could never succeed in the UK.

But succeed it did. Steve Auckland, managing director of Associated Newspapers' free division, says: "Metro is the third most-read newspaper in the UK: only the Daily Mail and The Sun have more readers. We charge roughly the same rates for advertising space as the paid-for titles and, while our ad revenue has taken a hit in the past 12 months, it was increasing until the first quarter of 2009. We expect to see a return to growth in Q2 2010, around the time of the football World Cup."

Elusive audiences

Auckland adds: "We are read by a group that is very difficult for advertisers to reach: graduates aged 30 to 35, with a high disposable income. People haven't yet been bombarded with marketing messages first thing in the morning, so they are more open to ads they see in Metro."

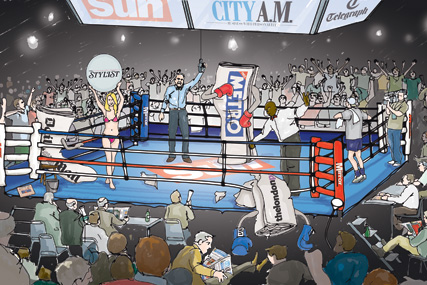

It is well documented how the rise of Metro - compounded by the launches of free newspapers CityAM, London Lite and thelondonpaper, as well as free magazines ShortList and Sport - has dealt the paid-for titles a body blow. Decades of stasis in the market left the traditional commuter papers poorly equipped to respond to their dynamic new competitors, and their circulations dipped accordingly. But the paid-for sector has finally started fighting back.

Martin Ashford, circulation director at the Financial Times, says: "We have been innovating through our direct delivery service and our voucher scheme. This has paid dividends, combined with our focus on being a trusted guide throughout the economic turmoil. We reported strong rises in the latest National Readership Survey and our print circulation rose 15% in the 12 months to March 2009. The FT's circulation revenue was up 20% over the same period."

With the paid-for titles starting to rally, the closure of thelondonpaper has prompted many to question the business sense of moving to an entirely free business model. Profits from free papers have been particularly elusive in the cut-throat evening market. In the year to 29 June 2008, thelondonpaper had a turnover of just £14.1m and made a loss of £12.9m. And although Auckland maintains London Lite's ad revenue is increasing, it also has yet to make a profit.

Dave Mulrenan, head of national press at ZenithOptimedia, comments: "The evening market has become over-saturated and commuters don't value London Lite and [the now defunct] thelondonpaper as much as Metro. This is reflected by the price of advertising in the free papers, which is about one-third of the price of the paid-for titles. It was no surprise to me when thelondonpaper announced its closure three years after launch."

The battle for the commuter press market will be won and lost on three fronts: distribution, price and content. Andrew Mullins, managing director at the London Evening Standard, admits his title failed to get its distribution strategy right in recent years. He says: "Our distributors receded into the background behind the gauntlet of the energetic, thrusting distributors of the freesheets. They became dispirited."

Jo Blake, head of press at Arena BLM, agrees distribution is essential. "Ease of availability is key," she says. "People live in a fast-moving society and they want their media to keep up. People buy Oyster cards, Starbucks cards and ready meals. They do not want to wait in line to buy their newspapers."

Mike Soutar, chief executive of ShortList Media, believes distribution has been central to the success of his free men's magazine ShortList.

He says: "About half our copies are distributed direct to tens of thousands of workplaces and high footfall places such as airport lounges, gyms and shops. The other half are distributed by hand.

"This model gets us into places the news-stand can't reach. This is why our ad revenue is increasing 80% year on year and why, two-and-a-half years in, we are achieving the targets we laid out in our original business plan."

Fighting back

But the London Evening Standard has learned its lessons. Mullins says: "We introduced the Eros Card, which people could use to pre-buy copies of the paper for as little as 15p a day, in November 2007. We have also added video screens to display units and since early 2009 we have been paying distributors by the hour rather than by the number of copies they sell. This keeps them motivated throughout the day."

At the same time, price remains important. Mullins is aware that when the London Evening Standard was given away free or heavily discounted, as trialled at key locations later in the evening from May, it reached a far wider audience. He says: "Our future is getting the Standard in front of Londoners. That's what brings in the advertising revenue."

Following this month's announcement to move to an entirely free model, he adds: "The commercial reality for newspapers is that the copies you distribute need to be read by a valuable audience that has a realistic chance of appearing on a readership survey. For us, as a London newspaper, getting large numbers of affluent and upmarket people to read your paper, and having them register on the NRS, can really only be achieved via free distribution within London. That is one of the main reasons we chose to go free."

Content is the final, all-important part of the jigsaw: whether a title is free or paid-for is ultimately less important than whether it has well-written content that appeals to a specific audience. London Lite and thelondonpaper were too similar to ensure both papers' continued survival, but Sport, ShortList and CityAM all provide information or entertainment on a clearly defined subject.

While these titles, like every free commuter publication except Metro, are yet to make a profit, they have invested in producing well-regarded products for affluent markets and most predict they will survive.

Most, that is, except Dominic Williams, press director at Carat, who is unsure whether Stylist will go the distance. He says: "ShortList Media's decision to launch Stylist is brave. There was a gap in the market for quality men's weeklies and the fact that ShortList is free helped to establish the title fairly quickly. However, there is already too much choice in women's weeklies. Once the novelty of its arrival has worn off, we will have to see whether Stylist will have the required quality to establish itself."

Furthermore, the issue of free versus paid-for newspapers could soon be rendered moot due to the advance of mobile technology.

Oli Roxburgh, managing director at mobile marketing agency Bluestar Mobile, says: "I don't need to wait to pick up my free paper on the train on the way to work. I can view my Twitter feed on my mobile, I can access the mobile website of my favourite newspaper and I can browse the mobile internet for a wealth of free content."

He adds: "The Guardian, The Times and The Daily Telegraph have already started to capitalise on the immense growth of the mobile internet by creating mobile portals. And if the wireless internet is introduced underground, as London Underground has expressed interest in trialling, this trend will be given even greater impetus."

Mullins envisages a future where the market is split between a younger audience, mostly making short journeys within the city centre and consuming more free content through print and mobile, and an older, affluent audience, mostly commuting in from the suburbs and prepared to pay for a more substantial read. It is an optimistic prediction from the publisher of a newly free newspaper, but the battle is not over yet. With rumblings of further seismic changes in the free newspaper market - most notably the question mark over the future of London Lite - the paid-for papers still have everything to play for.

Giving it away Free: distribution strategies

AM: Metro dominates the morning free newspaper market, distributed in 33 major urban centres. Metro posted a circulation of 1,331,806 in June and its NRS figure of 3,476,000 for the 12 months to April 2009 makes it the UK's third most-read national newspaper. The rate card for a national page in Metro is £35,000.

More than 90% of Metro's copies are distributed using bins or racks on public transport, although this system may be challenged in March 2010, when the paper's London Under-ground contract expires. However, a tender process for the contract is under way and few expect Associated Newspapers to lose out.

Meanwhile, daily business and financial newspaper CityAM and weekly men's magazine ShortList have made progress by appealing to specific audiences.

CityAM, which launched in 2005, was initially distributed at seven London stations between 6.30am and 9.30am to catch traders, bankers, analysts and stockbrokers. However, it has recently shifted its distribution strategy to placing copies directly in workplaces. In July, CityAM recorded a circulation rise of 3.4% year on year to 88,800, making it the highest climber in the free newspaper market.

In the same month, ShortList recorded a circulation of 511,000. Half its copies are distributed directly into offices, airports, gyms and shops such as French Connection, while the other half are handed out on the streets in 11 major cities in England and Scotland.

ShortList Media is trying to replicate that success with free women's weekly Stylist, which launched on 7 October in London, Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, Glasgow and Brighton with a print run of 400,000 copies.

PM: Russian billionaire Alexander Lebedev bought the Evening Standard in January and launched the renamed London Evening Standard in April with a fresh editorial stance. It gave out free copies after 7.30pm from May, and became fully free this week.

Having withdrawn from the national ABC audit, the Standard reported a debut regional ABC of 236,075 for the first half of 2009, with 61.1% of its circulation coming from paid-for copies. Those figures represented a circulation rise of 12% compared with May, but a year-on-year fall of 20%.

Following the demise of thelondonpaper, the Standard's only challenger in the capital's evening newspaper market is London Lite. However, despite the Lite's July NRS figure of 1,169,000, which makes it the most-read evening paper in London, rumours of its imminent demise are rife, with some claiming its only purpose was to act as a spoiler product to News International's thelondonpaper.

Outside the capital, the Manchester Evening News remains a significant, if dwindling, presence. Since March 2005, the MEN has handed out free copies in the city centre, with suburban readers continuing to pay for the paper. Since then, the paper's paid-for sales have fallen by about a third and it withdrew from ABC reporting earlier this year. In the second half of 2008, the MEN had a circulation of 153,724, with 81,092 copies handed out and 72,632 sold.

In August, The Daily Telegraph tested the free market by striking a deal with gin manufacturer Gordon's to sponsor a six-week trial of free paper The Friday. TMG printed 150,000 copies of the lifestyle-focused title and distributed it in the afternoon at 25 railway stations nationwide and with the Friday edition of The Telegraph. However, TMG would not comment on whether the experiment was a success.