Amid the turmoil of 2020, the UKŌĆÖs creators were presented with an ambitious brief: design a nationwide festival that could unite the public and ŌĆ£showcase the UKŌĆÖs creativity and innovation to the worldŌĆØ.

Festival UK 2022, the working title for the ┬Ż120m, government-funded initiative, is due to take place in two yearsŌĆÖ time. Following the October entry deadline, the event organisers will select 30 creative teams to develop and pitch their ideas early next year and, from those, commission 10 final projects to form the festival.

Since former prime minister Theresa May announced the plan in 2018 and Boris Johnson gave it the go-ahead last year, critics have dubbed it a ŌĆ£festival of BrexitŌĆØ, warned it could inflame tensions in Northern Ireland, because the timing clashes with the centenary of IrelandŌĆÖs partition and civil war, and called it a waste of public funds.

But at such a fragile and divisive time for the country, the festivalŌĆÖs chief creative officer, Martin Green, who was previously head of ceremonies at the London 2012 Olympics, argues: ŌĆ£Work that seeks to bring us together in greater understanding, navigate our way through differences and change the world is required more than ever.ŌĆØ

In the eventŌĆÖs scope and ambition, there are echoes of the 1951 Festival of Britain, which drew more than eight million visitors for a celebration of British innovation, arts and sciences at LondonŌĆÖs South Bank in the wake of the Second World War.

Beyond this historic comparison, however, it is hard to imagine what this next festival might be. It lacks a name and brand, which will be decided after the projects are commissioned.

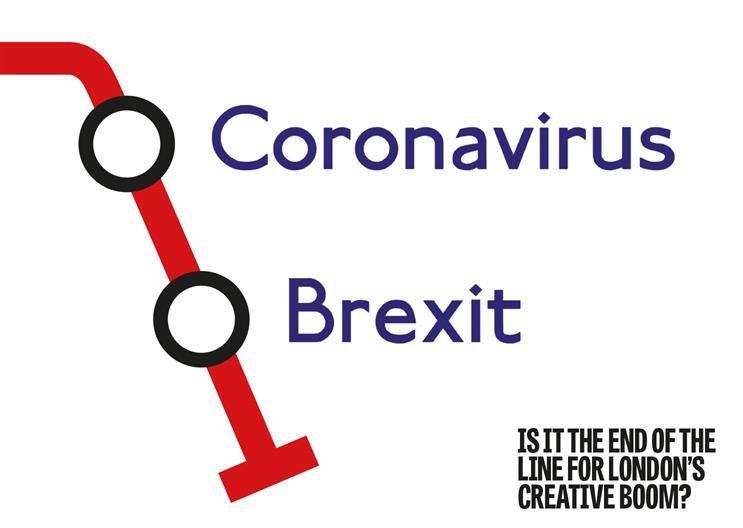

And the creative sector, which the event seeks to buoy and promote, is also in flux. First came the spectre of Brexit, then the economic and cultural upheaval of Covid-19 ŌĆō two forces that are reshaping UK society. By the time the festival comes around in 2022, the creative landscape it reflects may be permanently altered, too.

Debates about the UKŌĆÖs creative future tend to start with London. It has long been the magnet that draws much of the country and the worldŌĆÖs brightest talent, but now some are questioning whether its future as a creative hub will be limited.

There have been growing pressure points in the city, such as high living costs, which may partly explain why London continuously reports some of the lowest average life satisfaction in the Office for National StatisticsŌĆÖ rankings of personal well-being.

Several London boroughs with persistently low well-being scores ŌĆō Camden, Islington, Lambeth and Hackney ŌĆō are also among the most expensive in which to rent and buy property.

Soon after the UK voted to leave the European Union in 2016, predictions began of LondonŌĆÖs decline as a global centre for business and culture. Ongoing uncertainty about Brexit has raised concerns about institutions moving their headquarters outside the UK or a talent drain from the capital.

Indeed, the latest ONS figures show that LondonŌĆÖs population is growing at its slowest rate in 15 years, due to an increase in international migration and people moving to other parts of the UK.

All this was before Covid-19 struck, and questions over LondonŌĆÖs future grew louder. The rise of remote working, social distancing and job losses have caused many to re-evaluate their living situations, with some seeking less densely populated or expensive areas.

The London Assembly Housing CommitteeŌĆÖs August survey revealed that one in seven Londoners (14%) wanted to leave the city as a result of the pandemic. In June, careers advisory service Escape the City found that the number of jobseekers looking outside the capital more than doubled compared with the same period in 2019 ŌĆō a trend that could accelerate with a second wave of the virus.

So far, London ŌĆō the countryŌĆÖs largest business, cultural and tourism hub ŌĆō is suffering ŌĆ£a deeper downturn and slower recovery than all other towns and cities in the UK and capitals in EuropeŌĆØ, The Telegraph reported in July.

Green is adamant that the ŌĆ£death knell of the city is a bit prematureŌĆ” capital cities will always draw in creatives and be hubs, because of their very nature as exciting places to beŌĆØ. But there is little doubt that London will change, just as it has after other crises.

For instance, after the Second World War, government policies aimed at rebalancing the nationŌĆÖs development and economy beyond the capital led to LondonŌĆÖs population shrinking by more than a fifth ŌĆō a loss of about two million people ŌĆō between 1941 and 1992, while the rest of the UK recorded steady population growth, according to a 2020 report by New London Architecture (NLA), The Changing Face of London.

When architect Richard Rogers and Labour MP Mark Fisher published their book A New London in 1992, they wrote of the city: ŌĆ£It no longer has a cohesive sense of identity. Its infrastructure has drastically declined. It is dirty, overcrowded, increasingly polarised between rich and poor, North and South.ŌĆØ

End of the renaissance?

Starting in the 1990s, New LabourŌĆÖs ŌĆ£urban renaissanceŌĆØ policies helped change LondonŌĆÖs fortunes. It also championed the creative industries, which, with the financial and tech sectors, have helped fuel economic growth for the capital and country. The most recent government figures show that the creative industries, including advertising and marketing, contributed more than ┬Ż111bn to the UK economy in 2018 and were growing more than five times faster than the national economy overall.

The UK ad market is heavily London-centric. ▒▒Š®╚³│Ąpk10ŌĆÖs research (see chart, above) shows 85% of the employees at all of the big six agency groups work in London ŌĆō in the case of WPP and Omnicom it is 90% and within Publicis Groupe it is 95%.

Some large media companies, including Google and Facebook, also show a similar geographical bias, although the BBC, ITV and Sky have a large presence in the regions.

But like much of the economy, many advertising and creative businesses have been hard hit by the pandemic. Group M forecast a 12.5% decline in the UK ad market in 2020, while arts and entertainment are among the worst affected sectors, reporting a 44.5% year-on-year drop in monthly gross domestic product (GDP) in the three months to June. With a large proportion of the creative sector based in London, its slump is likely to make an impact on the city, too.

One obvious effect is a diminishing of LondonŌĆÖs buzzing, creative atmosphere, as theatres go dark, music venues remain shuttered and many other cultural institutions face an uncertain future. The shift to remote working is also reshaping the urban environment as fewer people travel into the city centre. In a sign of the pain being suffered by London, the Mayor, Sadiq Khan, has asked the UK government for a ┬Ż5.7bn bailout of the public transport network because of plunging passenger numbers.

New Commercial Arts (NCA), the agency launched in May by Adam & Eve founders James Murphy and David Golding, was ready to set up shop in Soho ŌĆō once home to numerous advertising agencies and production companies ŌĆō when Covid changed its plans. Since lockdown, Murphy and Golding have held on to their office, with a few employees going in occasionally for meetings, but most of the time they are working remotely, like countless other companies. It is quite a shift from the early days of Adam & Eve, and from what Murphy and Golding envisioned when they decided to leave the creative powerhouse they had built to start again.

ŌĆ£One of the reasons we did a start-up is itŌĆÖs a very enjoyable experience of a small gang of people in a tight space, working more intensively. ItŌĆÖs a different experience now,ŌĆØ Murphy says. NCA has about 15 employees but ŌĆ£over half of those people weŌĆÖve never physically met, and at least half of them are scattered outside LondonŌĆØ, he says.

This new way of working will have a ŌĆ£long-term effectŌĆØ on the industry, Murphy predicts. For a long time, what has set the UKŌĆÖs advertising market apart is ŌĆ£a strong central gravityŌĆØ, he explains. In countries such as the US and Germany, there are several large hubs of business and culture, but in the UK, that activity is predominantly concentrated in London.

ŌĆ£WhatŌĆÖs really powerful and unique about the UK industry is itŌĆÖs been very geographically centred in central London. That description of a village industry has been uniquely applicable to the UK,ŌĆØ Murphy says. ŌĆ£Some people would say thatŌĆÖs been a bad thing, but itŌĆÖs definitely created a unique energy, buzz and competitive edge. One of the reasons it punched above its weight globally is because weŌĆÖre all sitting cheek by jowl, fighting each other.ŌĆØ

'Capital cities will always draw in creatives because they are exciting places to be'

ŌĆö Martin Green, Festival UK 2022

Murphy may be nostalgic for the days of running into friends and rivals on the streets of central London, but he senses more frustration among his younger employees, who are ŌĆ£wanting to come to a place of work and feeling like theyŌĆÖre missing out on some learning and growingŌĆØ.

As NCA is finding, ŌĆ£creative businesses understand better than most the need for team working and the ability to actually get together and talk about ideasŌĆØ, Peter Murray, curator-in-chief of NLA, says. ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre still going to require central spaces where people come together to share ideas, operate as teams and do things that are actually difficult to do well in a virtual environment.ŌĆØ

'Geography will become less relevant'

How the creative community solves this problem in the era of Covid could subtly alter the fabric of the city. NCA, for example, wants to transform its hardly used Soho office into ŌĆ£more of a creative space, rather than one where you arrive at 9am and sit there till 5:30 doing admin and day-to-day tasksŌĆØ, Murphy says.

Such rejigs have led Murray to conclude that the UK is ŌĆ£about to go into a new creative periodŌĆØ, because ŌĆ£we are faced with huge problems, and huge problems need creativity in order to deliver better environments and smarter citiesŌĆØ.

He points to the example of the 1970s recession, when he started his career as an architect. ŌĆ£It was a dire time but you had a lot of architects without much work who spent a lot of time thinking and creating ideas. Out of that came a hugely creative period that is partly responsible for the ascendancy of British architecture, with the likes of Zaha Hadid, who helped drive cultural revival in the UK,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Periods of economic decline can deliver positive creative growth.ŌĆØ

Murray predicts there will be particularly strong growth among emerging companies, which might be more adaptable or able to take advantage of trends such as falling office rents in central London.

The fledgling NCA has already seen some benefits to its business in this time of upheaval, because remote working enables ŌĆ£small agencies to compete globally, and regional agencies to compete more with London agenciesŌĆØ, Murphy says.

ŌĆ£Small agencies have been able to turn up at pitches in exactly the same way as big agencies. It doesnŌĆÖt help to have a big office with an impressive reception when youŌĆÖre all just sitting on a Zoom call. Geography, by definition, will become less relevant.ŌĆØ

While it faces enormous challenges, the UKŌĆÖs creative scene has a strong foundation because of its talent pool, heritage and reputation, which so far ŌĆ£hasnŌĆÖt been as damaged as we thoughtŌĆØ it would be by Brexit, Murphy says.

Instead of collapsing, what is more likely is that ŌĆ£the places where culture happens spread outŌĆØ, Lisa Taylor, director of consultancy Coherent Cities, says.

This movement was already evident before the pandemic, as creative founders scattered even within the capital, to mini hubs in areas like East London.

More broadly, though, social media and then lockdown have helped to ŌĆ£democratiseŌĆØ creativity, Taylor says. The closure of venues has meant more art galleries, theatres and comedians are taking their shows online and opening their work up to wider audiences ŌĆō a trend that observers expect to continue and permanently change the way in which the creative industries operate.

This explains why Green has an open-ended view of Festival UK 2022. He says: ŌĆ£These projects donŌĆÖt need to be in a single venue, in a single place, on a single day. It could be 10 million tiny things over a number of days.ŌĆØ

Covid, which hit when festival planning was already under way, only intensified the need for creative ideas to work ŌĆ£in a totally distanced world or in a non-socially distant worldŌĆØ, he adds.

While Green and his team have drawn inspiration from the Festival of Britain, he maintains that there is a fundamental difference between the two, because it was ŌĆ£a destination event in our capital city. If you whip forward to 2012, the last time we had this kind of resource to spend on a creative act, we did it in a stadium in London and received it through broadcast. We donŌĆÖt live like that any more.ŌĆØ

It is also telling that the festival organisers have their headquarters in Birmingham, rather than London. Birmingham will be the site of the 2022 Commonwealth Games, but the location was also chosen because ŌĆ£it was very important to us that the core organisation for this project was not based in LondonŌĆØ, Green says.

ŌĆ£We had an opportunity here to commission work that is for everybody and expand the frame of reference,ŌĆØ he adds. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve said [to creative teams] that their ambition should be that each piece of work reaches 66 million people ŌĆō the symbolic number of the countryŌĆÖs population. Once you start making work that seeks to treat the whole of the UK as a place, you become borderless. You can make work that a lot of people anywhere in the world can connect with.ŌĆØ

The rise of the regions

GreenŌĆÖs ambition mirrors a larger government push, as Boris JohnsonŌĆÖs administration has promised to tackle regional inequality and rebalance the economy beyond London.

In few areas of the economy is this imbalance between the capital and regions more conspicuous than in the creative industries. It is not just the big global advertising groups that are biased towards London. Fifty per cent of the whole advertising industry is based in the capital, the UK Advertising in a Digital Age report found, compared with about 13% of the UK population living in the capital.

Not only is employment in the creative sector disproportionately located in London, but this regional inequality has been increasing, according to the Creative Industries Policy & Evidence CentreŌĆÖs analysis of 2019 figures from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. ŌĆ£Employment growth in the rest of the UK would have to increase fivefold over its current trend to catch up [to LondonŌĆÖs creative sector] in 20 years,ŌĆØ the report states.

Covid might close that gap faster if the trends of remote working and people wanting to leave London continue. Before the pandemic, there had been a growing awareness within advertising and media of the untapped potential of the regions.

Companies such as Channel 4, WPP and Dentsu International had started moving more jobs from London to the rest of the UK.

Helen Kimber, managing partner at The Longhouse, a headhunting company for the creative industries, has observed the appeal of regional agencies among job seekers looking for opportunities beyond LondonŌĆÖs ŌĆ£oversubscribed marketŌĆØ.

Channel 4 set up a new national headquarters in Leeds in 2019 and is set to move in properly next year, following delays caused by Covid. Janine Smith, who joined Channel 4 this year as digital content director, moved from London to Leeds for the role but insists she is an exception. ŌĆ£We havenŌĆÖt taken loads of people from London and just moved them up to Leeds,ŌĆØ she says.

Crucially, this means C4ŌĆÖs new recruits ŌĆō many of whom come from the North, and havenŌĆÖt previously worked at a big broadcaster ŌĆō have a ŌĆ£diversity of viewpointsŌĆØ, Smith says: ŌĆ£They donŌĆÖt have the homogenous background of people who have always worked in media and live in east London.ŌĆØ

'Periods of economic decline can deliver positive creative growth'

ŌĆö Peter Murray, NLA

Smith is hinting at an issue in the creative industries that goes much deeper than location. Advertising is the sixth-most-elitist industry in the UK, sociologists Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison revealed in their 2019 book The Class Ceiling.

This is borne out by the fact that seven in 10 of the ad industryŌĆÖs employees grew up in an AB household ŌĆō meaning those with professional or managerial jobs ŌĆō compared with just three in 10 of the mainstream, according to a 2020 study from Reach Solutions, The Aspiration Window.

And the gap is widening, Wavemaker North planning director Lisa Thompson wrote in a recent ▒▒Š®╚³│Ąpk10 article: the percentage of employees from privileged backgrounds increased from 52% in 2014 to 55% in 2019, while the percentage of those from working-class backgrounds decreased from 19% to 15%.

A central base in London is one important factor contributing to the industryŌĆÖs lack of social diversity ŌĆō ŌĆ£location is intrinsically linked to social classŌĆØ, Thompson says ŌĆō but it is not the only one.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs easy for people to let themselves off the hook and say this [problem] is purely London-based,ŌĆØ Andrew Tenzer, director of group insight at Reach Solutions and author of The Aspiration Window report, says. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm not convinced that a better geographical spread is going to prevent us falling into traps that we naturally fall into anyway: we recruit people who are similar to ourselves.ŌĆØ

Tenzer points out that creative businesses attempting to improve social diversity by simply moving jobs outside of London could overlook their own recruitment biases and the fact that many people lack the proper conditions to work remotely, as well as the knowledge, contacts and skills that have traditionally been vital to get a foot in the door.

This problem is not unique to the ad industry, but ŌĆ£other industries are not aiming to connect with a huge percentage of the population. This is hard to do if youŌĆÖre completely under-representative of the population,ŌĆØ Tenzer says.

Notably, as Festival UK 2022 solicits submissions, its eligibility requirements specify that creative teams must ŌĆ£show a clear and demonstrable focus on platforming underrepresented, new and emerging organisations, artists, practitioners and thinkersŌĆØ.

To Green, a greater diversity of creatives is important because ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt think you can make work about the world we live in if the team making that work doesnŌĆÖt look like the world we live in.ŌĆØ

If his mission is successful, the festival could display a UK creative sector that has finally reckoned with how it represents the world. Green is full of optimism, but such a hopeful promise should be treated with caution ŌĆō the public has heard such proclamations before.

Two decades ago, under the New Labour regime, headlines declared the era of ŌĆ£Cool BritanniaŌĆØ. The Blair administrationŌĆÖs championing of the creative industries, and the image it burnished of the UK as a flourishing powerhouse of culture and creativity, is a legacy that lasts to this day. But as author Zadie Smith noted earlier this year in an episode of The Adam Buxton Podcast: ŌĆ£The question was, whose Cool Britannia? There was also another ŌĆścool BritanniaŌĆÖ going onŌĆ” in all these little pockets that were nothing to do with mainstream life.ŌĆØ

As Smith observes, the overarching vision of UK creativity has long been rife with blindspots, and it has left many behind. ŌĆ£The industry has a white, middle-class, male face,ŌĆØ Thompson says. Today, its other legacy is one of gaping geographic, socio-economic, gender and racial inequalities.

Now, 2020 has pushed the UKŌĆÖs creative sector to a turning point, and those inequalities have become too glaring to ignore. As it considers its future, whose cool Britannia is it going to create next?

Adland looks very different when you're not based in London

Simon Gwynn on the view from north of the border

Since the start of lockdown, IŌĆÖve been living in Glasgow ŌĆō in a neighbourhood with a large Pakistani community. My sense is that people from this group are about as underrepresented in UK marketing as it gets and that points to a more fundamental issue.

The London-centricity of the ad industry means that some perspectives are rarely brought to the table and, as a result, businesses can end up relying on mistaken assumptions about the consumers theyŌĆÖre trying to reach.

A company that wants to appeal to all of the UK should consider that its people are likely to be more effective if they are located on the ground in different types of places. Every time I visit my home city, Sheffield, I become aware of how little I know about the issues on peopleŌĆÖs minds there and their conversations.

The pace, cost and nature of human interactions in London have a big impact on peopleŌĆÖs expectations of life, regardless of their background, lifestyle or income. These factors make it quite unlike anywhere else in the UK, including the next tier of cities. At least, thatŌĆÖs how it was before March this year.

The lockdown has forced companies to throw away assumptions about where their staff need to be to do their jobs; the rebuilding should prompt new thinking about the best geographical structure

for understanding the market youŌĆÖre trying to serve.

You donŌĆÖt need to have an office in Sunderland, Swansea or Southampton. There are people in those places, though, who would make invaluable additions to your team, but have never considered a career in marketing, donŌĆÖt believe itŌĆÖs possible or just donŌĆÖt want to move away from home. So the question is: what do you plan to do to access that talent?