Chutzpah & Chutzpah. Could there have been a more fitting title for the book published last year in which former Saatchi & Saatchi staffers offered their first-hand accounts of what it was like working for the agency during its barnstorming years?

The Saatchi brothers had chutzpah in spades. They didn’t have a coherent advertising philosophy – Charles thought ads were either "terrific" or "shit" – and the astonishing expansion of their organisation was down to the voracious acquisition spree that would return to haunt them.

They began in September 1970 and the agency’s star burned bright in those early, buccaneering days. Young hotshots such as Jeremy Sinclair, John Hegarty and Tim Bell all joined in 1970, followed by Bill Muirhead in 1972 and Martin Sorrell in 1975.

It was a time not only of a revolution in the arts and a breaking down of class barriers but of growing consumer spending power. The Saatchi mantra that "nothing is impossible" encapsulated a new, breezy selfconfidence. So it was entirely apposite that it should have played a key role in helping Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives to power.

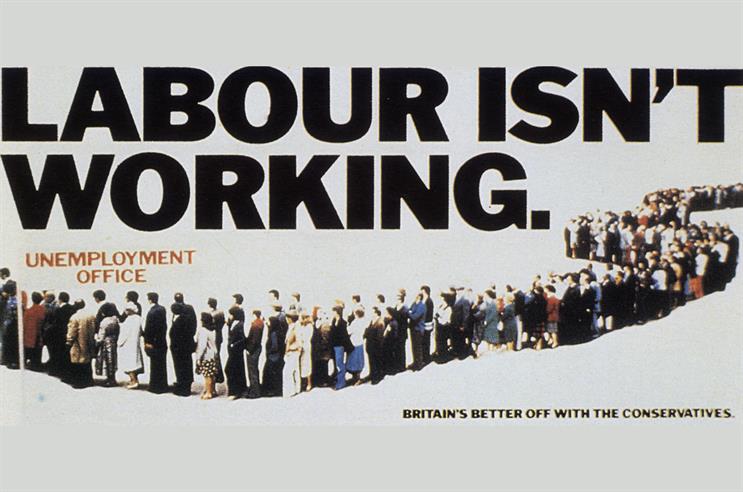

The agency produced some remarkably good work – from "Labour isn’t working" for the Tories (1978) and Silk Cut’s "Slashed purple" (1983) to the epic "Manhattan" spot for British Airways (1983) and The Independent’s launch campaign "It is. Are you?" (1986).

At the time, Charles just wanted the biggest and best agency network in the world and all the fame and fortune that came with it. He craved success, and his fearsome chair-chucking rages were a manifestation of this.

What marked out the brothers as different was their nerve in pushing things as far as they could. At the same time, they were also innocents upon the advertising stage. If they ignored conventions – like the one preventing IPA agencies poaching each other’s business – it was because they didn’t know such rules existed.

Quite how Saatchi & Saatchi made such a profound impact on the industry defies easy explanation. Undoubtedly, both Charles’ instinct for publicity, which got the Saatchi name known well beyond the industry, and Maurice’s business acumen and relentless salesmanship had a lot to do with it.

Or perhaps it was their tireless energy. Or their knack of employing talented people or identifying a new trend. Or their focused approach to new business – in which prospects were called methodically at regular intervals – something Maurice learned as a junior assistant at Haymarket when helping to launch ±±ľ©Čüłµpk10.

However, it is equally true to say that the Saatchis taught the ad industry a lesson that nobody would wish to repeat – that acquisition for its own sake and with little thought given to integration is a recipe for disaster.

Certainly, nobody seemed to consider the long-term consequences of the mind-blowing $450m 1985 takeover of Ted Bates, then a pillar of the Madison Avenue establishment and the world’s third-biggest agency. It had clients asking why they should be paying 15% commission to big agencies when the Bates deal suggested they were awash with money.

They made an abortive bid to buy Midland Bank in 1987, which proved to be the harbinger of the collapse of the Saatchi empire, leading to the ousting of the brothers at the end of 1994. They set up M&C Saatchi, while Publicis Groupe later bought their old agency. Charles’ interest turned to his art collection, leaving Maurice to reflect on the rise and crash of Saatchi & Saatchi as a salutary lesson.

Read the full run-down of ±±ľ©Čüłµpk10's top 20 agencies of the last 50 years here.

Below we look back at some of the work that made Saatchi & Saatchi reach number six on the list, including all-time classic ads for British Airways, Club 18-30 and Direct Line.

Health Education Council "Pregnant man" (1969)

Conservative Party "Labour isn’t working" (1978)

Silk Cut "Slash" (1983)

British Airways "Manhattan" (1983)

The Independent "It is. Are you?" (1986)

Castlemaine XXXX "Sherry" (1986)

Club 18-30 (1995)

British Army "Operation Kenya" (2000)

Club 18-30 "Sexual acts" (2002)

.jpg)

.jpeg)