Watch Jeremy Lee discuss the work

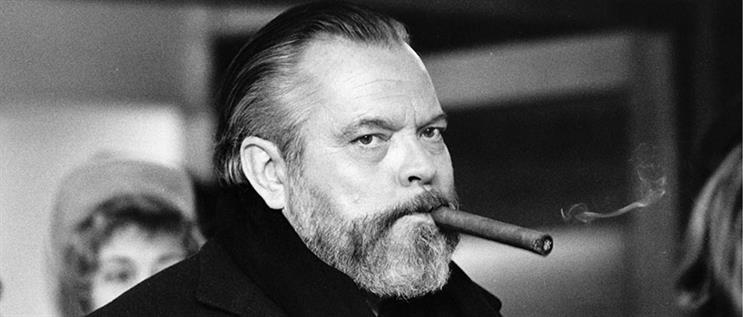

To some, the reliance of Orson Welles on commercial work is evidence of just how far his career had slumped since his creation of Citizen Kane in 1941 – arguably the best film ever made. How funny, how washed-up, how tragic.

But to others – including Welles himself who was more pragmatic about advertising and had voiced radio ads throughout his career – acting in ads for products so mundane as frozen food, booze and photocopiers was a useful way to raise funds for his film projects. Moreover, his deep, booming voice lent itself to advertising and, as Welles himself admitted, he lent class and gravitas to products that otherwise were lacking.

Far from being on his uppers, Welles was financially secure. But he was struggling to get finance from Hollywood, and from 1970 until his death in 1985 he tried to finance The Other Side of the Wind, a comeback film about a director who needs backers to bankroll his comeback film.

Welles earned the contemporary equivalent of $75,000 a day for his commercial work, according to Josh Karp’s book, Orson Welles’s Last Movie, and he needed it.

The experimental film was beset with financial and legal problems and wasn’t completed until 33 years after his death. It eventually had its world premiere at the 75th Venice International Film Festival in August 2018 and was released in November 2018 by Netflix, to critical praise.

It was obviously worth the wait, much like the Paul Masson wine to which Welles will forever be linked.

[Main image: Getty]

Relationship freezes with Findus and JWT

J Walter Thompson’s attempt to court Welles to front its advertising for Findus didn’t get off to the best start. To his outrage, the agency demanded that Welles – who had one of the most distinct baritone voices of his generation – record an audition tape for the part.

"Surely to god there’s someone in your little agency who knows what my voice sounds like?" he later recalled telling JWT in an interview. Enraged by this, he demanded payment in advance but then proceeded to lead the agency a very merry dance indeed.

JWT requested that he come to a studio in Wardour Street but shortly beforehand he told them that he’d be in Paris and that they’d have to come to him. When they arrived at the George V Hotel, they were informed he’d checked out the previous day.

Welles left a message that he was in Venice but upon arrival there was another message telling them to meet him in Vienna. "I made them chase me all around Europe with their shitty little tape recorder for 10 days. They were sorry they made me audition," he later recalled.

He made four spots for the frozen-food brand, and the relationship between him and the agency didn’t really improve much. He frequently went to battle against the copywriters ("this is shit", he told the writer of the "Beef burgers" spot) and producers. They found him difficult to work with, too, and one sound recordist secretly compiled a tape of his outbursts, which was released some years later.

It reveals him to be irascible but also a perfectionist who put his all into the performance and was trying to improve the script – his frustration with poor copywriting for a product as prosaic as frozen peas is perhaps understandable.

One of his most famous outbursts on the bootleg recording – "I’ve spent 20 times more for you people than any other commercial I’ve ever made. You are such pests. In the depths of your ignorance, what is it you want?" – summed up his attitude to the project.

The finished films still retain a beauty, though, thanks to Welles’ distinctive tone.

Paul Masson shablee…

Welles’ contempt for the hand that fed him reached its height in his most famous campaign – a three-year partnership with low-end Californian wine brand Paul Masson, reportedly worth $500,000 a year.

Speaking of the people who worked at DDB Needham, he said: "I have never seen more seedier, about-to-be-fired sad sacks than were responsible for those Paul Masson ads. The agency hated me because I kept trying to improve their copy." The person designated to handle the account – and therefore Welles – was John Annarino, who in 2013 said of the encounter: "It was no picnic."

Welles made eight TV commercials and a series of print ads for Paul Masson, all of which used variants of the much-parodied slogan: "We will sell no wine before its time." The campaign didn’t get off to the best start when on the first shoot Welles objected to the director saying "Action!", meeting it with silence. Welles eventually growled: "Don’t say ‘Action’. Don’t say anything."

Welles wasn’t afraid to make improvements to the script. In the 1979 "Gone with the wind" spot for Paul Masson’s Emerald Dry wine, he dismissed the original script he was given, which compared the wine to a Stradivarius violin. That’s not to say that Welles wasn’t partial to the "nice, pleasant little cheap wine". Annarino recalled: "Orson liked Paul Masson’s cabernet. He often called the ad agency and instructed, ‘Send more red.’"

Welles’ most famous performance for the brand came in the 1980 "French" spot for its sparkling-wine variant. In a tape leaked some years after the ad aired, an inebriated Welles slurs his way through his lines while struggling to remain upright. Fortunately the agency managed to use retakes, cuts away from Welles to the bottle and some dubbing by Welles at a later date.

Despite Welles’ behaviour on set, the campaign was a success, with sales growing a reported 30%. However, the tie came to an end in 1981, after Welles told the press that, for health reasons, he no longer drank wine.

Thanks to Welles’ drunken performance and erratic behaviour, the ads have become embedded in popular culture, even if Paul Masson has not.

Yes to Carlsberg. No to the Love Boat

Welles’ links to the advertising industry were almost as strong as they were to the Hollywood studios that he came to loathe later in life.

The furore over his War of the Worlds radio broadcast, which supposedly resulted in mass panic and hysteria (see below), was a myth perpetuated by newspapers. They saw this relatively new medium steal their ad revenue and therefore wanted to paint it in a negative and irresponsible light.

Welles also appeared as the boss of an ad agency in the Michael Winner film I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname – not the most flattering portrait of the industry.

But Welles was less idealistic and discerning about ad appearances than films and TV shows. He once said: "On my tombstone, I want written, ‘He never did Love Boat.’" Unlike many contemporaries, he did not guest-star in the schmaltzy drama set on a luxury cruise ship but he did put his name to a variety of brands, with the quality of the ads as diverse as the products.

One of the most resonant were his voiceovers for Carlsberg, where his baritone lent a gravitas to a lager that had only its Danish heritage as a differentiator.

The "Probably the best lager in the world" strapline, created by KMP Advertising, launched in 1973 and continued to be used up until 2011.

Welles’ sonorous tone and beautiful storytelling helped make it one of the most famous straplines of all time, although in a 1973 review in 北京赛车pk10, an anonymous creative director wrote that the campaign wouldn’t endure as it was "a self-conscious path". After many years Welles became too expensive and was replaced by Canadian voiceover artist Bill Mitchell.

Welles' alien invasion

The impact of this adaptation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds helped establish a mythology around Welles, who directed and narrated the radio play. It was performed and broadcast live in the US on 30 October 1938. Its illusion of realism was heightened as it aired in a news-bulletin format without commercial interruptions. Newspapers – which were threatened by the impact on scarce ad revenues that nascent radio presented – hyped up its influence, even though research at the time showed that less than 2% of the population had heard it. Within three weeks, the newspapers had published at least 12,500 articles about the broadcast and its impact. Initially apologetic about the "panic" it had caused, Welles later embraced the story as part of his personal myth.

The impact of this adaptation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds helped establish a mythology around Welles, who directed and narrated the radio play. It was performed and broadcast live in the US on 30 October 1938. Its illusion of realism was heightened as it aired in a news-bulletin format without commercial interruptions. Newspapers – which were threatened by the impact on scarce ad revenues that nascent radio presented – hyped up its influence, even though research at the time showed that less than 2% of the population had heard it. Within three weeks, the newspapers had published at least 12,500 articles about the broadcast and its impact. Initially apologetic about the "panic" it had caused, Welles later embraced the story as part of his personal myth.

The ads timeline

1969 Eastern Airlines

Welles lent his godlike tones to this Young & Rubicam campaign in one of his first TV voiceover jobs.

1972 Jim Beam

This ad, featuring Welles and his daughter Rebecca, was the first of many associations with booze brands. Welles called his stints as a pitchman: "The most innocent form of whoring I know."

1977 Perrier

Perrier attempted to convince Americans to drink bottled water with a series of ads from 1977. "More quenching, more refreshing, and a mixer par excellence," Welles intoned, in a welcome change from peddling booze.

1978 Vivitar

Vivitar’s built-in flash was seen as revolutionary at the time and Welles – who, in 2002, was voted the greatest film director of all time in two British Film Institute polls among directors and critics – was the perfect man to extol its virtues.

1978 Domecq Sherry

In his 1966 film Chimes at Midnight, Welles played Falstaff and recited a Shakespearean speech in praise of sherry. Nine years later, Domecq hired him for a series of UK TV ads.

1979 G&G Nikka Whisky

Welles alleged that this campaign cost him a five-year French cognac contract when the owner of the cognac company saw it while in Hong Kong when it wasn’t meant to be running.

1981 Dark Tower

Launched at the height of the role-playing game craze, arguably this spot helped Welles land the role of narrator for the Revenge of the Nerds trailer three years later.

1985 Nashua Copiers

In his twenties, Welles directed an adaptation of Macbethwith an entirely African-American cast. Aged 70, he was quoting Shakespeare to flog photocopiers.