There isn’t anything particularly new in "breaking the fourth wall" – either within culture or advertising, which so slavishly tries to follow it and, on some occasions, is bombastic enough to think it creates it.

20th-century cinema stars such as Oliver Hardy and Charlie Chaplin used the technique to generate laughs in their early silent movies in much the same way that comedian Jack Dee did 80 years later when supposedly talking to the off-screen film crew and then hamming it up to the viewer in a bid to flog John Smith’s cans that now included a widget.

But what is new is the technique of addressing audiences directly and knowingly. Making a mockery of the conceit upon which traditional advertising conventions have been built seems to be an increasing trend. In fact, you could almost argue that taking a sarcastic or meta take on advertising is in danger of becoming one of the clichés that it seeks to explode.

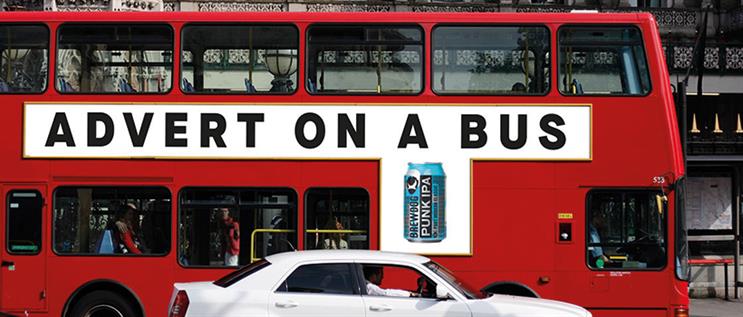

Recent examples – both of which managed to split both popular and industry opinion – include Uncommon Creative Studio’s "Advert" campaign for BrewDog earlier this year, something it claimed was "the most honest ad ever", and the latest instalment of The Corner’s campaign for Oasis, which promised to stop advertising if people bought its products.

Skittles took going meta a step further in February with its Skittles Commercial: the Broadway Musical, created by DDB Worldwide and Smuggler. Playing on the same night as the Super Bowl in which Skittles traditionally was an advertiser, the onenight-only 30-minute play critiqued advertising techniques and morality (one song was called Advertising Ruins Everything and aimed to sympathise with audience exasperation over how advertising permeates their lives). While the musical only played to a small audience, the hype ahead of its launch and its subversive nature generated headlines and awareness that perhaps a traditional TV spot would never manage.

In 2016, DDB Sydney launched its "For those who buy the car, not the ad" campaign for Skoda Octavia. While the spot was filled with the usual tropes – empty winding roads, beautiful scenic backdrop, a sweeping orchestral soundtrack – the stereotypical voiceover was interrupted by an actress in the passenger seat turning to the camera and saying: "You’re not seriously buying all this, are you?"

Coincidentally, this was in the same year that LeBron James told viewers of the Super Bowl that he’d "never tell them" to drink Sprite in the Wieden & Kennedy New York spot "Wanna Sprite". The ad poked fun at celebrity endorsements – James has been a Sprite brand spokesman since 2002 and it included a cameo by hip-hop artist Lil Yachty, who performed a parody of his hit single Minnesota – in an attempt to link transparency of product and purpose. However, it reverted to more traditional techniques later in the ad when James said that he’d only "never tell them to drink Sprite" because he’d "ask them if they ‘wanna Sprite’" instead.

This year’s BrewDog "Advert" ad was particularly divisive given that it came from a brand that had previously eschewed advertising as part of its "punk" approach. The 2013 claim by its co-founder James Watt that he would "rather take my money and set fire to it" than spend it on advertising and that "it’s the antithesis of everything we stand for and everything we believe in. It’s a medium that is shallow, it’s fake and we want nothing to do with it" is now infamous.

Having trousered his share of approximately £213m for selling a 22% stake to a private equity company, this anti-advertising-light approach seemed hollow – no matter how creatively "honest" the campaign was. Meanwhile, Oasis has long taken a tongue-incheek approach to its advertising. Its 2015 "O refreshing stuff" campaign featured posters with the copy: "It’s summer. You’re thirsty. We’ve got sales targets." The current outdoor campaign goes one step further by promising to stop advertising if sales targets are met, shifting the dial from being honest to apologetic. The copy on the sites starts "We know you don’t like ads" but caused a mini-backlash, at least among the ad industry commentariat, for the perception that it talked the business down. This is something that The Corner refutes.

So what does this say about the state of the advertising industry? Is there a crisis of confidence among marketers and agencies in the effectiveness of traditional advertising, or a feeling of being apologetic for being part of advertising at all? In some regards, it could reflect a view that current levels of creativity are just bland – Oasis’ "Togetherness" campaign last summer took the rise out of the high levels of perceived brand virtue signalling at that time – and that this is a way of cutting through.

Moreover, it could be a tacit acknowledgment that some audiences – particularly younger ones – have worked out advertising’s shtick and want the unexpected; by opening up advertising’s conceit and playing with it (in a knowing rather than critical way), it is possible to have fun and engage audiences in a non-traditional way.

In that regard, it’s no different from Groucho Marx telling the cinema audience of his 1932 film Horse Feathers to "go out to the lobby" during Chico Marx’s piano interlude.

'Nailing the lid on our own coffin'

By Clare Hutchison, executive strategy director, Havas London

So, if I started writing an article about writing an article, it would be super interesting, right? The haunting isolation of the blank page… my own personal conflict with my consciousness… the cold and empty sensation of the black keys as my fingers tap out every, single, wretched letter on my MacBook Air.

Wrong.

It would, quite frankly, be dull.

Self-obsessed.

And just a little bit pointless.

Let alone pretentious.

But this is exactly what brands such as Oasis and BrewDog have been doing recently.

Advertising about advertising. Marketing about marketing.

Essentially, they’ve gone meta.

But, the first thing to say is that this isn’t new.

Meta marketing has many predecessors.

Metafiction, metacinema, metadrama… all dropping the fourth wall and sharing a postmodern self-consciousness.

But this goes further: it’s not just advertising that is conscious of its own medium. It is critical. It’s disdainful. Advertising that pretends not to be advertising. Or at the very least to dislike advertising. "Unadvertising." Advertising that purports to be more "honest", "refreshing", "transparent". But the sad truth is that this is still mainstream brand behaviour. Brands spending thousands of pounds to buy very conventional media spaces – TV ads, six-sheets, radio ads (no matter how little an ad actually costs to make). And their objective is the same as almost every other brand that inhabits those spaces: the express aim of getting more people to buy their product. So why the gameplay?

If you’re being charitable you could say it’s just brands building off an insight.

In a world where millennials and Gen Z are actually paying to avoid what we do, it’s fair to say that it’s a truth that we have failed to engage the imagination of the next gen. Havas’ Meaningful Brands study has quantified the chasm that we face: if 75% of brands disappeared tomorrow, no-one would care. Ouch. But does gratuitously celebrating the fact that people hate what we do make them feel more positive about the brands that have gone meta?

So I didn’t ask Alexa.

I asked Twitter.

Clearly this isn’t quant, but taking two of the brands, Oasis vs BrewDog, one definitely fared better than the other.

There wasn’t much love for Oasis.

In fact, it did the reverse. Rather than tuning into this generation’s disdain for advertising, it reminded them that there are actually more important things to worry about than advertising. Things like packaging and plastic.

And while there was a bit of disdain for BrewDog…

There was also a lot of love…

But, interestingly, it’s not the "unadvertising" part that people love.

It’s the music.

Advertising doing what advertising does best. Harnessing and celebrating the cultural zeitgeist.

So. Some people like it, but I’d argue that this isn’t really building any strong or long-term positive brand associations. You wanna be famous for being a hater? Cool.

Like school kids slagging each other off in the playground, it might feel clever at the time but it doesn’t really achieve anything.

If we want people to fall in love with what we do, to really value it, we just need to be better at it.

We need to be smarter, cleverer, more entertaining.

We used to be culture. We used to be celebrated.

We used to be the water-cooler moment and the "top 100" countdown.

So, let’s stop wasting energy doing ourselves down, and invest our time in reinventing, reimagining.

It’s time for redux if we want to engage the next generation. Not self-flagellation.

Slagging ourselves off seems to be the sure way to nailing the lid on our own coffin.

Now that really is meta.

'These are ad campaigns in search of an idea'

By Amelia Torode, co-founder, The Fawnbrake Collective

When I look at the Oasis and BrewDog "anti-advertising" ad campaigns, I am reminded of the René Magritte painting Ceci N’est Pas Une Pipe: a pipe with the words "this is not a pipe" painted in French underneath. It is obviously a pipe, but the artist says it’s not. Magritte paints one thing and draws another. You think you know but maybe you don’t. While I am not saying today’s advertising is groundbreaking surrealist art, I do believe that the cultural context of today and the surrealist movement of the 1920s have more than a few similarities.

Then and now, we live in disconcerting times. We inhabit a world that often does not seem to make sense, a world where pre-conceptions are turned upside down and questions and challenges abound. We seek to expand our horizons and want to look at things with a fresh perspective – what we think are certainties just aren’t any more.

I believe that art and advertising are uniquely anchored in popular culture and concerns, so it is fascinating to take a step back and have a think about what this current trend might mean.

Are brands embarrassed about advertising? Embarrassed about being seen to be in need of advertising? Certainly, some brands appear to be.

Monzo famously and proudly scorned advertising. However, I attended one of its "open office" nights recently, where the brand gave a "radically transparent" talk about the advertising that it was about to run and why it thought that it needed it (who knew, advertising works).

Likewise, BrewDog doesn’t believe in advertising, except when it does. Surreal.

Naked advertising, advertising with nothing on. The un-ads. The non-advertising advertising. Or the opposite, advertising cunningly disguised as something else.

So we create branded content, brand experiences, brand-response mailers instead. But to real people, it’s all advertising – they still see it and understand it as advertising.

We know that consumers are clever. We know that they get it. Everyone has seen the advertising episodes of The Apprentice, so in effect everyone has seen behind the curtains and knows how our tricks are done. Which is why I think we are witnessing a proliferation of "you know it’s advertising" ad campaigns.

But these campaigns depress me. They are ad campaigns in search of an idea.

"You know that this is advertising" is not an idea. It’s a conceit.

We acknowledge intelligence of the public but then don’t credit them with enough imagination to participate in an idea. Call me old-fashioned, but I am still partial to the creative bit of our industry.

As our world gets more confusing, I think we will see more of this "tell it like it is" approach. But what we need now is the opposite. It is times like this that call for greater creativity and more expansive and imaginative ideas. It’s time for us to take more pride in the art and craft of our industry, a creative industry that changes the commercial fortunes of businesses. And there’s nothing surreal about that.