A borefest. A headpunch. An eyestab. A mindpain. A timewaste. A lostday. A thoughtfuck. A workpuke. A wordspurt. A shitshop. A lifesuck. A bumscrum. A chatbinge. A shoutshower. A hopemunch. A dreamcrush. A heartsink. A traincrash. A trendsplash. A deathwish. A sensewipe. A joysteal. A bullsesh. A headmess. A blooddrain. A jobcry. A teamscream. A twitglut. A craicden. A pleasestop.

As you can see, I am entering into the spirit of things, by producing vast quantities of ideas, of execrable quality, in the hope that one or two work.

Alex Osborne – the adman who is sometimes credited with inventing the brainstorm and who claimed it delivered a 50% improvement in creative performance – would no doubt be proud. But academics who have subjected the technique to empirical scrutiny might sound a more cautionary note. For instance, in a meta-analysis of 241 studies published in the Psychological Bulletin, one group of researchers reported that brainstorming actually has few positive effects in the workplace and probably impedes productivity when it comes to complex creative challenges.

There are two main reasons why this is the case. Firstly, not all brainstorm participants contribute to the same degree. Some coast, safe in the knowledge that others will do the brunt of the work. Others dominate, intimidating colleagues with their seniority, forcefulness or just sheer volume.

But, as Susan Cain has pointed out in her best-seller Quiet, many great innovators are introverts – and they are literally not heard above the corporate posturing. Secondly, group-think tends to gravitate around average ideas. Social scientists call this "regression to the norm" but we might call it "murder by marker pen". Genuinely disruptive ideas are either killed off by some crude voting exercise at the end of the session or neutered by merging with a separate suggestion.

Devotees will, of course, counter that I am simply describing bad brainstorming and that a professional facilitator can overcome these obstacles. There’s some truth in this (although in my experience, these experts come with their own instruments of torture, such as buttock-clenchingly awkward ice breaker games, role-playing exercises and team challenges).

But even the best facilitators, with the most willing participants, rarely come up with the goods. Why? Because, by definition, the kind of challenge that tempts you to assemble an entire department or whole swathe of senior management, is unlikely to be solved – or even hugely advanced – in a couple of hours.

The truth is that brainstorms are popular for all the wrong reasons. They feel democratic – but invariably have hidden hierarchies. They purport to champion revolution but typically reward convention. They promise sudden breakthroughs to problems that are often long-running and complex. Most of all, they masquerade as action but represent yet another excuse for organisations to talk, rather than do. What they are emphatically not, despite their ubiquity, is a proven method of generating step-change ideas that will ever make an impact on the real world.

Ironically - for the methodology whose motto is that "there’s no such thing as a bad idea" - it turns out that convening an offsite beano, where people introduce themselves as their favourite fruit and refrain from criticising patently stupid suggestions, while wearing ill-fitting chinos, is usually a pretty bad one.

Hey – "chinobeano", there’s another one.

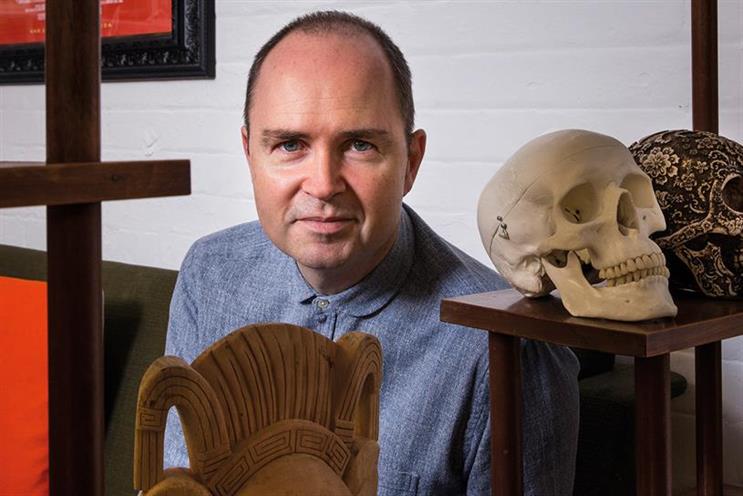

Andy Nairn is founding partner of Lucky Generals